Who is Stanislovas Tomas? He calls himself a Lithuanian lawyer, human rights defender, and professor at the Sorbonne.

But he is neither a lawyer nor a professor at the Sorbonne. (According to Euroradio, he wrote his doctoral dissertation there.)

He was a legal assistant but lost this status for "gross violations of ethics". In 2016 the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) ruled that Tomas wasn’t a lawyer and permanently banned him from representing applicants or assisting on cases pending before the ECHR.

In 2019, Tomas came to the attention of law enforcement agencies on suspicion of fraud. He offered to file a class action suit at the ECHR for Lithuanians seeking higher pensions, and charge the pensioners 50 euros apiece for his services. He obviously shouldn't represent their interests at ECHR, having no lawyer status.

A "Lawyer" for Belarus

During the Belarusian-Lithuanian border crisis in 2021, Tomas offered legal service to illegal migrants in Lithuania. He became a popular personality on state-run Belarusian TV.

In December 2021, he applied for political asylum in Belarus due to criminal prosecution in Lithuania. In March 2023, Belarus became Tomas’ client, he claimed on his website.

Tomas was able to attend the March meeting of CESCR as a "representative of civil society". This right belongs to public organizations that have submitted alternative reports on situations in the country they represent.

At least two organizations affiliated with Tomas have filed alternate reports. EgLex from Monaco and the Holocaust Victims Foundation, registered in the Channel Islands. Tomas previously made appeals to the UN on behalf of EgLex. Documents for the Holocaust Victims Foundation points to a connection with EgLex.

Reports of both organizations do not mention Belarusian potash sanctions. The Holocaust Victims Foundation alternate report deals with Tomas and his activities in Lithuania.

Tomas's complaint that Lithuania's restrictions on the export of Belarusian fertilizers may violate the right of Africans not to starve was taken up by CESCR, according to the statement published on his Telegram channel in February 2023.

The Belarusian Investigative Center (BIC) has sent a request to CESCR asking whether they received such a complaint. We are still waiting for a reply.

CESCR consists of 18 independent experts from different countries. According to the organization's website, they are "of high moral character and recognized competence in the field of human rights".

A resolution they adopted is a long list of recommendations on poverty, discrimination, climate change and other issues. There was also a proposal to review the restrictions on the supply of potash fertilizers from Belarus to African and Latin American countries, which are said to have led to "a negative impact on food security in these countries".

Potassium on the global market

The National Statistical Committee of Belarus has classified data on the export of Belarusian potassium after sanctions were imposed.

Open media information has led us to the conclusion that these sanctions are not affecting hunger in Africa.

In 2022, after the imposition of sanctions, potash supply on the global market was 60 million tons and only 39 million tons were used.

Very little Belarusian fertilizer went to developing countries. In 2020, Belarus supplied only $123 million worth of potash to African countries Total export of potash fertilizers amounted to about $2.4 billion, according to media reports. Most of the African exports went to Morocco, Egypt and South Africa, countries far from the poorest on the continent.

Belarus mainly supplied potash to Brazil, which did not impose any ban due to US and European sanctions.

But due to delivery difficulties, Belarus’ share of the Brazilian market

decreased from 18% in 2021 to 9% in 2022. The Belarus ambassador to Brazil said in an interview with BelTA YouTube channel in March 2023 that Canadian and American fertilizer producers are making up the difference.

The situation is similar in India. In 2021, it was the third-largest importer of Belarusian potash in the world. In 2022, imports almost halved , from $306.97 million to $168.52 million, despite higher prices. Moreover, $118.67 million of those deliveries were made before the imposition of sanctions. Competitors have sharply boosted potassium exports to India.

Belarus is increasing exports to China. Revenue for January-February 2023 amounted to $895.36 million, compared to $569.83 million for the same period in 2022. But according to Kommersant Outlet, Belarus has had to discount prices as much as 50 percent.

There is no shortage of potash fertilizer on the global market, supply exceeds demand, consumption has slightly decreased, and Belarusian potash fertilizers under sanctions have been replaced by fertilizers from other countries.

Effect on food security

According to 2022-23 data from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), world cereal production amounted to 2,786.5 million tons and consumption was 2777.6 million tons, a

surplus of 8.9 million tons. In 2018-19, before the imposition of sanctions, there was a cereal shortage of 40 million tons in the world.

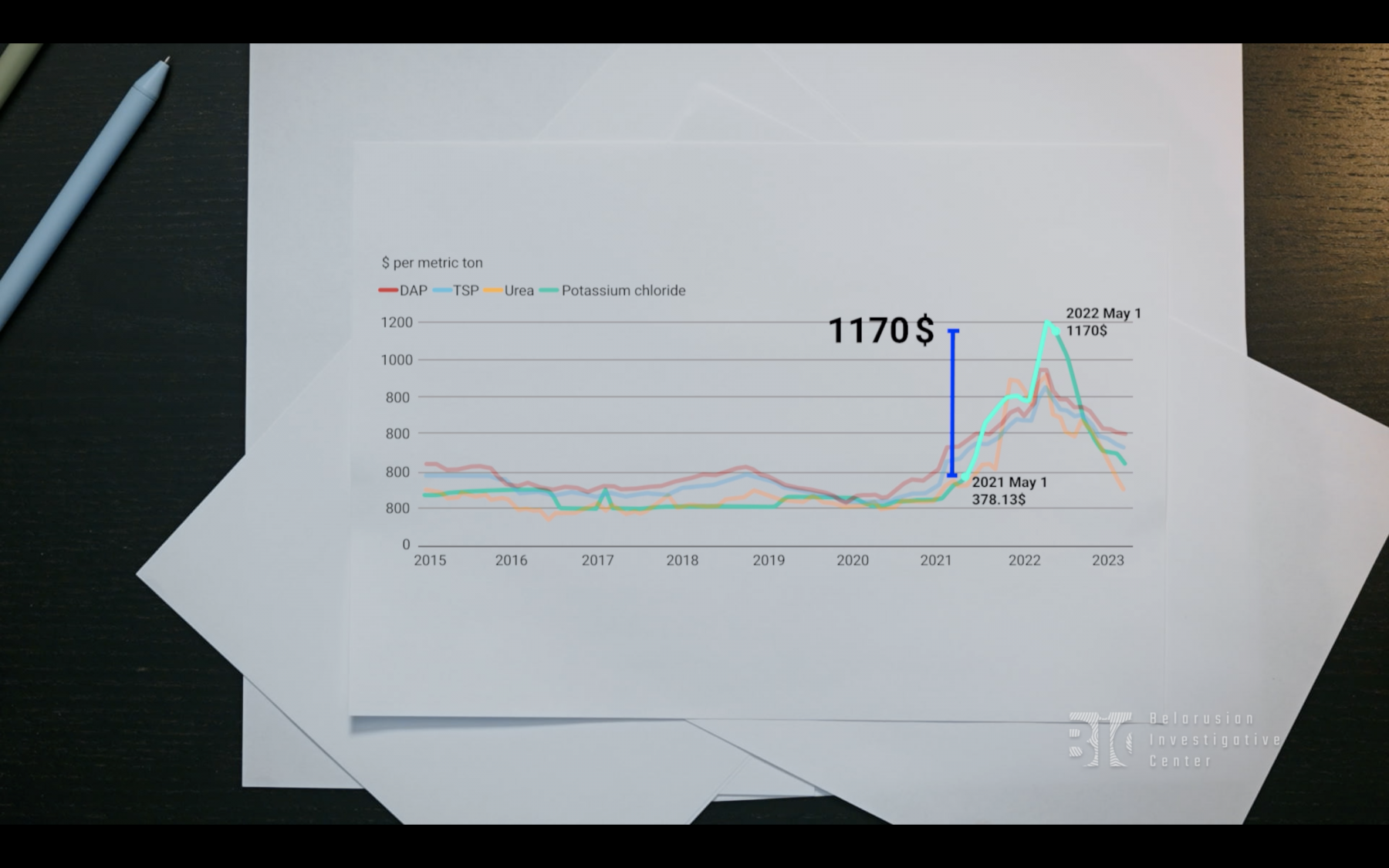

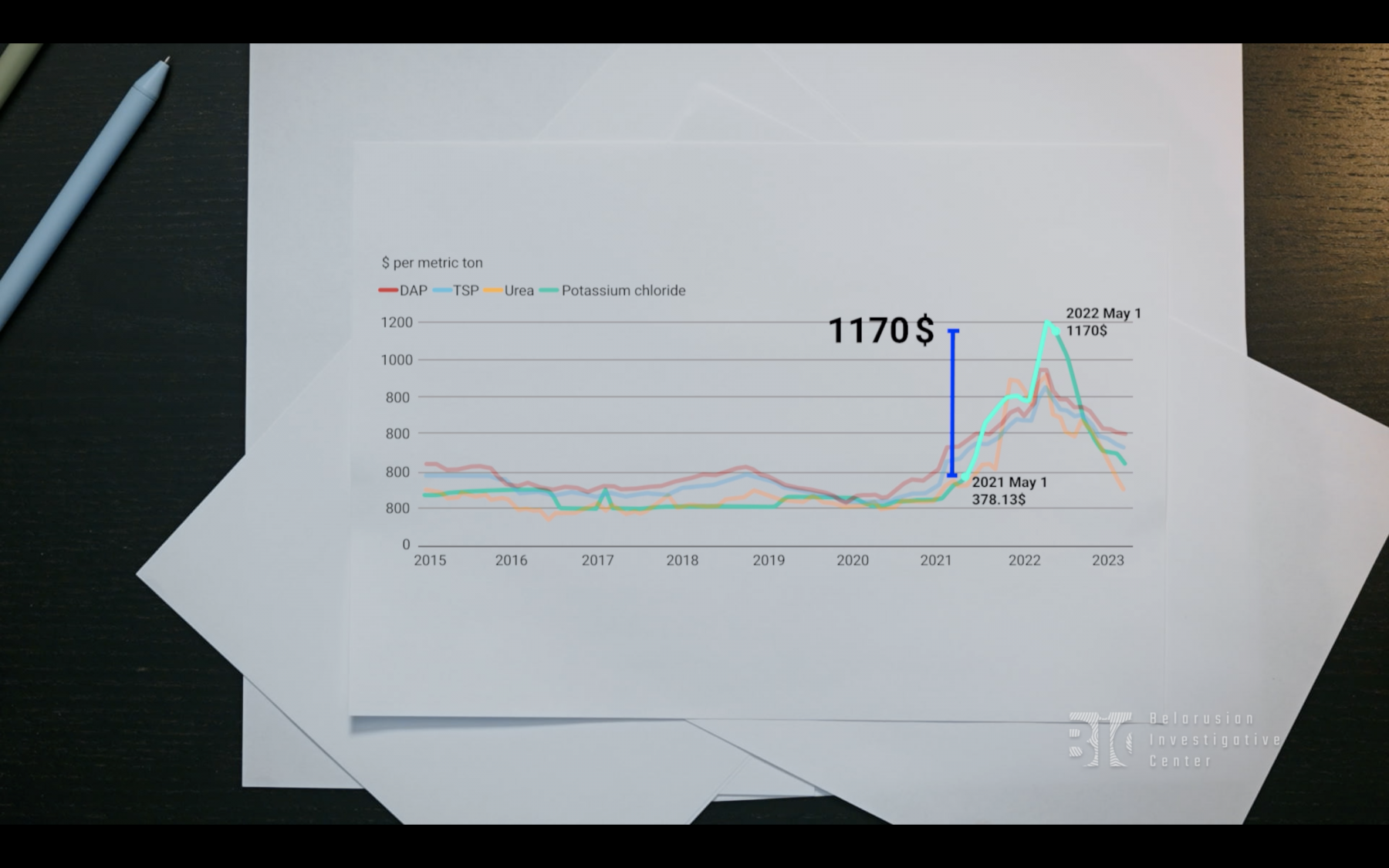

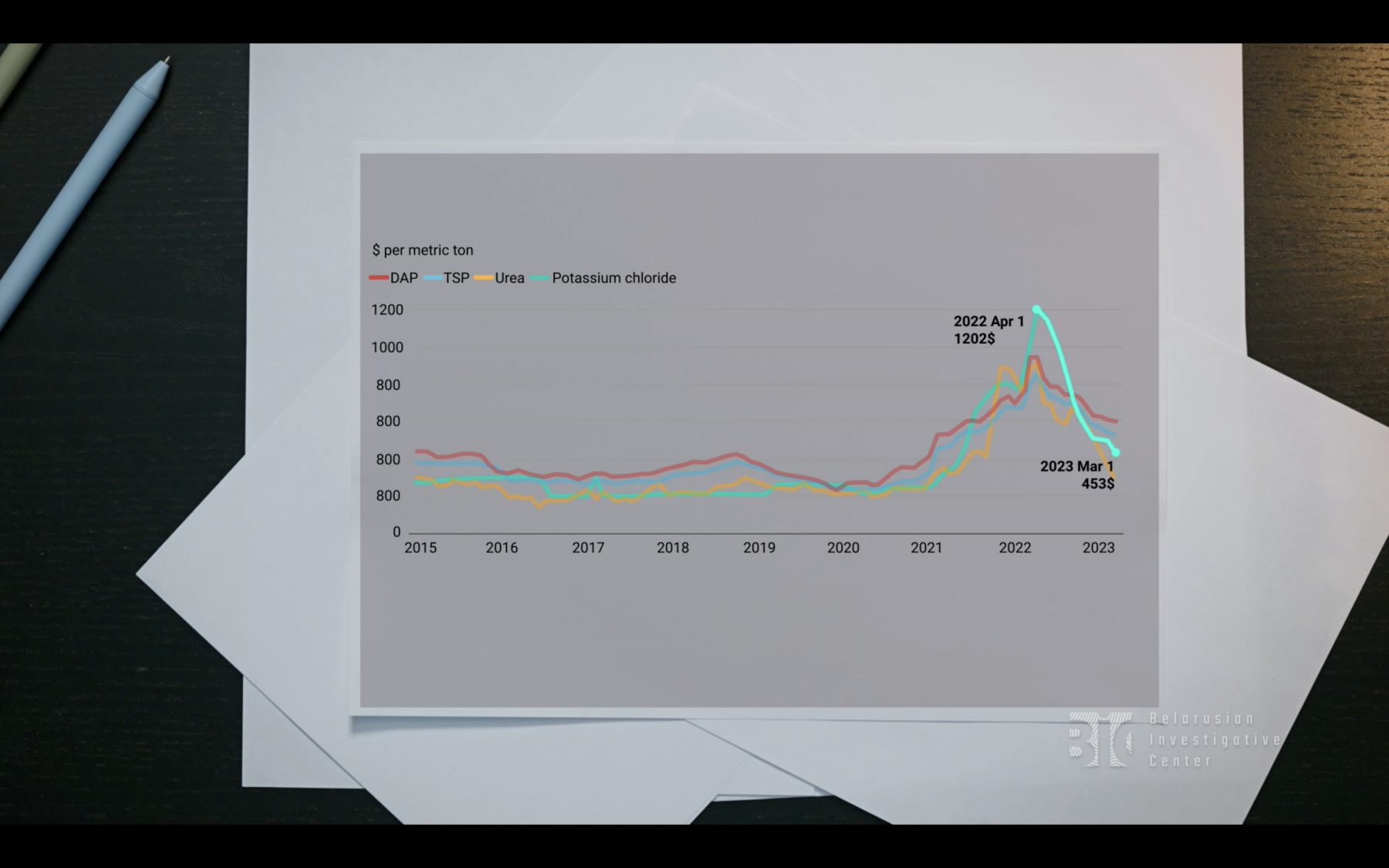

Any shortage of Belarusian fertilizers didn’t cause food insecurity in developing countries. Record increase in prices for fertilizers and, hence, for cereal, were responsible, From May 2021 to May 2022, the price of potash tripled to $1,170 per ton. For the same period, cereal prices almost doubled, up to $522 per ton.

When fertilizer and grain supplies are abundant, but developing countries do not have enough money to meet minimum needs, the programs of the World Bank, IMF, and other private and international non-profit organizations help. But international assistance doesn’t reach everyone on time.

Russia played on anxiety, leading to panic

What caused the rise in world prices? Psychological factors provoked it.

According to experts from the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), fear of immediate shortages caused many countries dependent on fertilizer imports from Russia and Belarus to begin looking for alternative supply sources.

There were market jitters around the world. Russia played on this, exacerbating the panic with statements and actions.

On March 10, 2022, Minister of Trade and Industry Denis Manturov, at a meeting with Russian president Vladimir Putin, said Russia would limit export of its fertilizers. He cited logistics problems.

Russian producers did indeed face problems with potash export. export of potash. Many of them, such as Uralkali and EuroChem, used sea terminals in the Baltic countries that were blocked due to EU sanctions after the military invasion of Ukraine.

To avoid worsening food security, the US and the EU excluded Russian potash from sanctions, classifiying it as an essential commodity. Russian ships with potassium were allowed to enter European ports.

Russia never introduced restrictions on its fertilizer exports. But Russian producers have almost halved mining.

Before 2013 they did it intermittently, probably to keep prices high. This time it looks the same. By the end of 2022, potash exports from Russiahad fallen by only 10%, but Russian fertilizer export revenue surged 70% as prices jumped, the Financial Times reported.

A surge in grain prices was also largely artificially provoked by Russia. It imposed a ban on its grain exports and at the same time blocked transportation of Ukrainian grain on the Black Sea.

The situation stabilized temporarily thanks to the Black Sea Grain Initiative.

Kremlin outplayed. Competitors enter the game

Russia provoking the rise in fertilizers and grain prices accelerated several potash mining projects which had previously been unprofitable.

International giant BHP Group Limited plans to accelerate the construction of the Jansen potash mine in Canada. According to BHP, by 2026 it will produce almost as much potassium as Belarus exported to Europe and the Americas.

US Mosaic, Canadian Nutrien, and Germany's K+S Group also announced plans to ramp up production and bring over 10 million tons to the market in the next 2-3 years. That will be enough to substitute completely the export of fertilizers from Belarus or Russia.

In 2023 the Canadian Millennial Potash Corp acquired the potash project Banio in Gabon. It covers 1238 sq. km and contains 1.7 billion tons of potash natural salts. One of the largest potash deposits in the world, its proximity to major markets in the Southern Hemisphere gives it a significant cost advantage.

All this explains why it is critical for the Belarusian authorities to ease the sanctions on potash as soon as possible before prices fall and many markets are completely lost.

The market has currently stabilized, so any lifting of sanctions on Belarusian fertilizers might have little effect.

In 2022, Canada and other exporters increased potash production at existing facilities and improved supplies. The price of oil fell from $120 per barrel in June 2022 to about $80 in March 2023, lowering transportation costs.

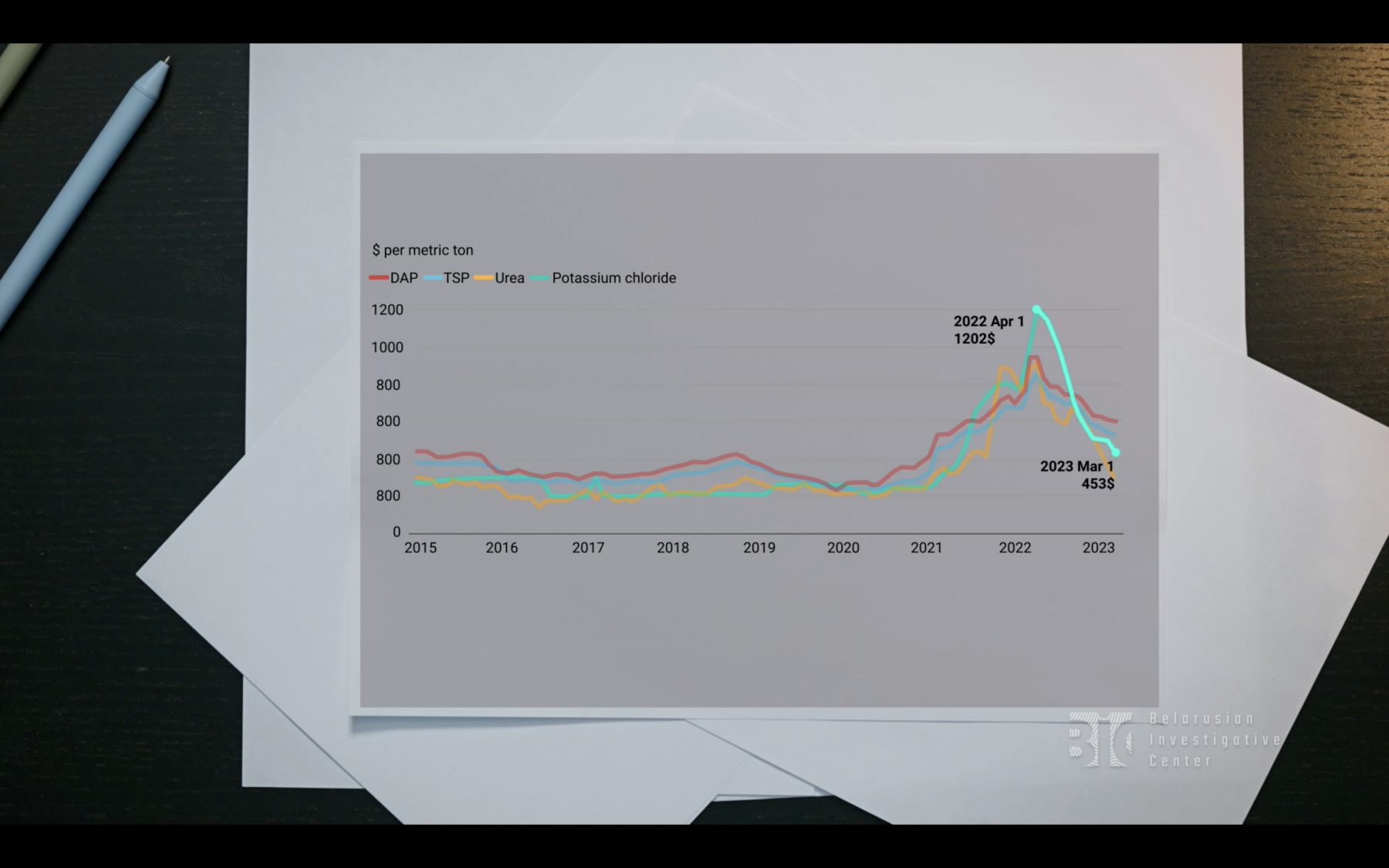

As a result, potash prices have almost tripled and returned to mid-2021 levels: from a record $1,202 per ton in April 2022 to $407.50 in April 2023.

According to analysts' prognoses, prices for potassium chloride in 2023 will decrease by almost 30% compared to 2022. In 2024 the price is expected to be about $300 per ton, the level of 2019, FitchRatings announces.

Through Russia to the global market

Despite the sanctions, Belarus managed to take advantage of the relatively high prices.

Authorities have classified export statistics. But according to the Institute of Natural Monopolies Research (IPEM), more than 2 million tons of Belarusian potassium were transported through Russia in the first quarter of 2023, Vedomosti reports. In 2022, Belarus transported 3.5 million tons through Russia.

If the pace continues through all of 2023, state-owned Belaruskali will export about 8.5 million tons of potassium through the Russian Federation, which is only a third less than in pre-sanction times.

But if prices decline, this transit is likely to decrease due to the high costs of transporting it by rail over long distances.

The distance from Soligorsk, the industrial center of Belarus, to Klaipeda, Lithuania, is 620 km.

The distance to Ust-Luga, Russia, is 1,5 times more, to Murmansk i about 4 times more, and to Vladivostok 16 times more.

Belarus authorities have tried to negotiate discounts with Russian Railways. As of January 2023, discounts are valid for Belarusian oil products transportation by Russian Railways, but not for potash fertilizers. No tariff changes have been publicly announced.

Lukashenko probably reduced exports in 2022 to negotiate a discount, but in 2023 he accepted the existing conditions to take advantage of high prices.

But Belarus is not able to export pre-sanctions volumes of potassium through Russia alone due to insufficient capacity of Russian ports. According to Alexander Goloviznin, Director for Logistics and Analytical Research at MorStroyTekhnologiya Llc, these capacities are barely enough for Russia to export its own fertilizers.

Since 2020, Belarus has been discussing building its own port in Russia, or buying and refurbishing an existing port. However, these issues are still “under development".

Several Russian banks are ready to lend for the construction of a Belarusian port, said the Belarus Minister of Transport and Communications. But no details about any agreements have been reported.

The Bronka port in St. Petersburg, which Minsk expected to buy out in 2023, has been sold to Moscow company NKK LOGISTICS LLC. News that the deal was completed came out on May 10.

According to St. Petersburg media outlet Fontanka, this company emerged aless than two years ago, its website does not work, and no one answered calls from Fontanka's journalists. There have been no media mentions of the owners of the port, Alexei Raspopov and Natalia Morozova.

A Fontanka source believes that NKK LOGISTICS LLC might resell the port to another owner who for some reason couldn't buy it directly. Perhaps, it will be Belarusians, but there is no indication so far.

Summary: Facts and Arguments of the UN Committee

The spikes in global prices for potash and grain were indeed partly caused by restrictions on the export of Belarusian potash. But Russia played a more significant role in the fertilizer and grain market.

The price spikes didn't cause a food shortage. They only lasted from March to August 2022 and then prices fell to their previous level as Western producers accelerated the opening of several large mines.

Potassium supplies from these deposits are expected to saturate the market and drive down prices even further in the long run.

All this argues against the UN Committee's reasoning for the need to lift sanctions against Belaruskali to reduce food insecurity in Africa.