Over 6,000 hip and 1,500 knee joins were being replaced each year in Belarus before the Covid-19 pandemic. Over 70 per cent of the implants were locally made. According to Mr. Dzmitry Pinievich, Belarus’s Minister for Health, Belarusian implants are as good as their foreign counterparts.

In Belarus joint-replacement operations are fully covered by the state healthcare system if the patient chooses locally made implants. But many prefer imported materials for better warranty terms, even if it means they must cover the additional cost – according to orthopaedic practitioners.

Patients are free to choose from any foreign-made implants as long as those are available for purchase in Belarus. American DePuy, German Waldemar Link, and Swiss Medacta are some of the most popular choices. A company Medlink used to offer stock and custom-made Walder implants before the crackdown.

Consumers would normally expect a clear relationship between a brand and its dealership network, especially when it comes to matters such as hip or knee replacement. But in Belarus things are different. For example, DePuy prosthetics (a brand owned by Johnson & Johnson) are being sold by an unknown sole trader Ms. Sviatlana Sytsik located in a regional town Smaliavichy. The Minsk Johnson & Johnson office has told us they had no agreement with Sviatlana Sytsik: “the corporate business model for Russia and CIS countries does not assume exclusive agreements, and our distributors are free to resell products to third parties. Our company does not control or regulate resell prices”.

As the middleman is free to set any price – resulting in 1.5 times the cost for elderly patients compared to their counterparts from other CIS countries – Mr. Aleksandr Lukashenko is blaming the doctors. According to him, they are “being given bribes in envelopes” for upselling foreign brands. But given similar crackdowns before, such as the 2019 ‘case of medics, it is implausible that the government is poorly informed in this matter.

Indeed, a 2021 CIS Anti-monopoly Intergovernmental Commission Report identifies “a state of monopoly for prosthetic hip implants in Belarus”. Although the report fails to mention any company names, evidence points to Altimed.

Industry insiders say the local market with its three major suppliers of foreign-made prosthetics has far less competition than its Russian counterpart where prices are lower. On top of that, Belarusian prosthetics manufacturers are being propped up via protective legislation and a convoluted certification regime that often makes them the cheaper option in tenders.

“Competition is key” – according to Mr. Andrei Kartuzou, a manager at Kryline, a prosthetics supplier. – “If you had at least 5-10 companies like they do in Poland, the prices would eventually go down. Manufacturers or dealers seeing poor sales because of competition would be lowering their prices”.

With over 2,000 patients on a waiting list for hip implants and almost 2,500 patients awaiting knee replacement surgery in Minsk alone, the major outcome of the latest crackdown against orthopaedics has been increased lead times for operations using foreign-made materials. Indeed, those who received treatment in March 2022 had been on a waiting list for five years. We have contacted a few hospitals under the disguise of a patient, and had our assessment confirmed by Municipal Clinic Number 6, Republican Scientific and Practical Center of Traumatology and Orthopedics, and even the Presidential Clinic.

Despite loud statements being made by the authorities condemning price gouging, our investigation has identified one clinic in Belarus where upselling foreign prosthetics is not frowned upon by Mr. Lukashenka. Clinic Mercy opened in 2021 and charges patients $6,500 – 8,000 for a full treatment including labour, hospital room, prosthetics, and other services. By contrast, a similar treatment would cost approximately $3,000 for a foreign implant at a public hospital. Although the clinic’s doctors also work at public hospitals, they have escaped the wrath of the crackdown despite their involvement with foreign-made prosthetics.

Sisters of Merci

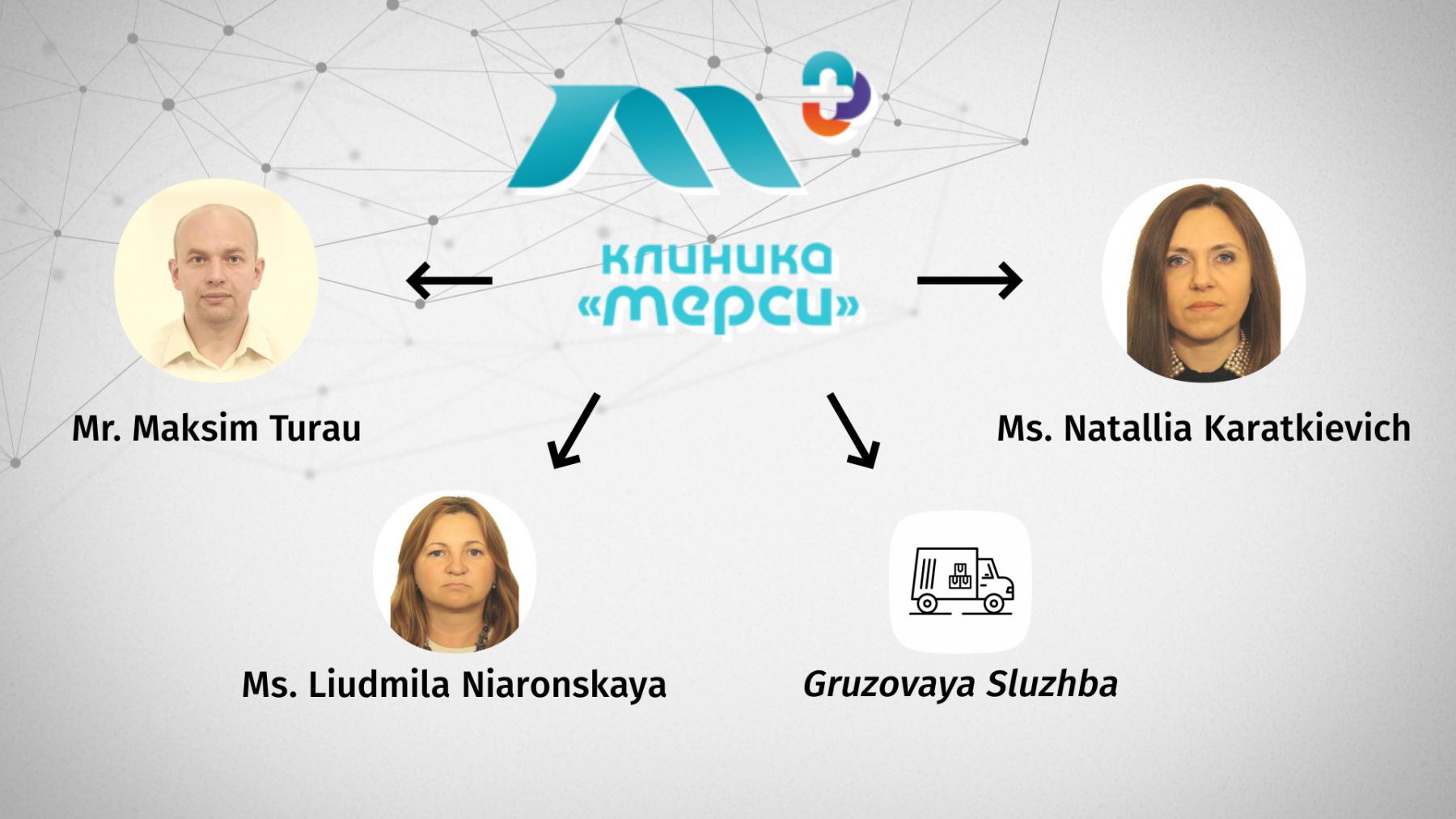

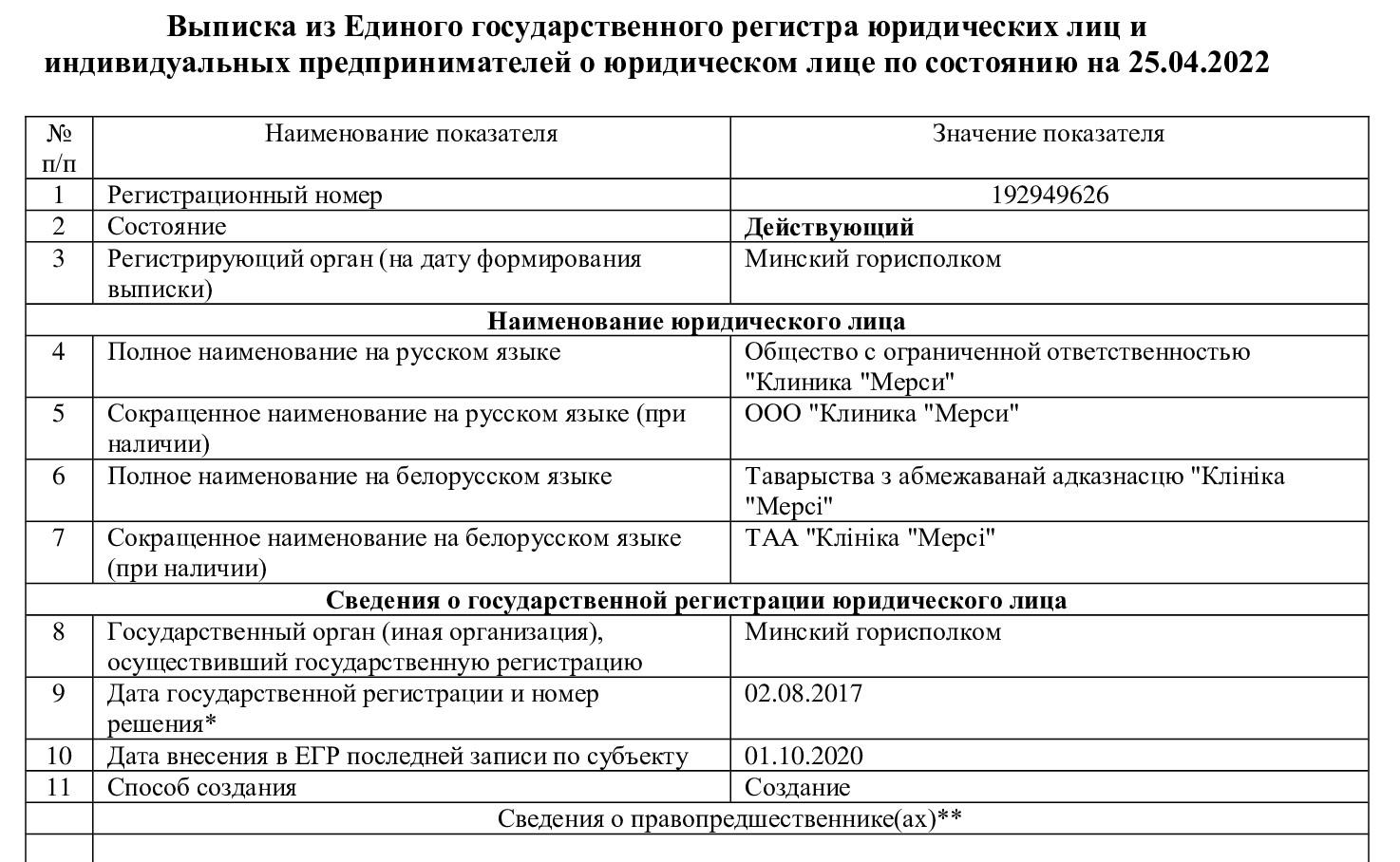

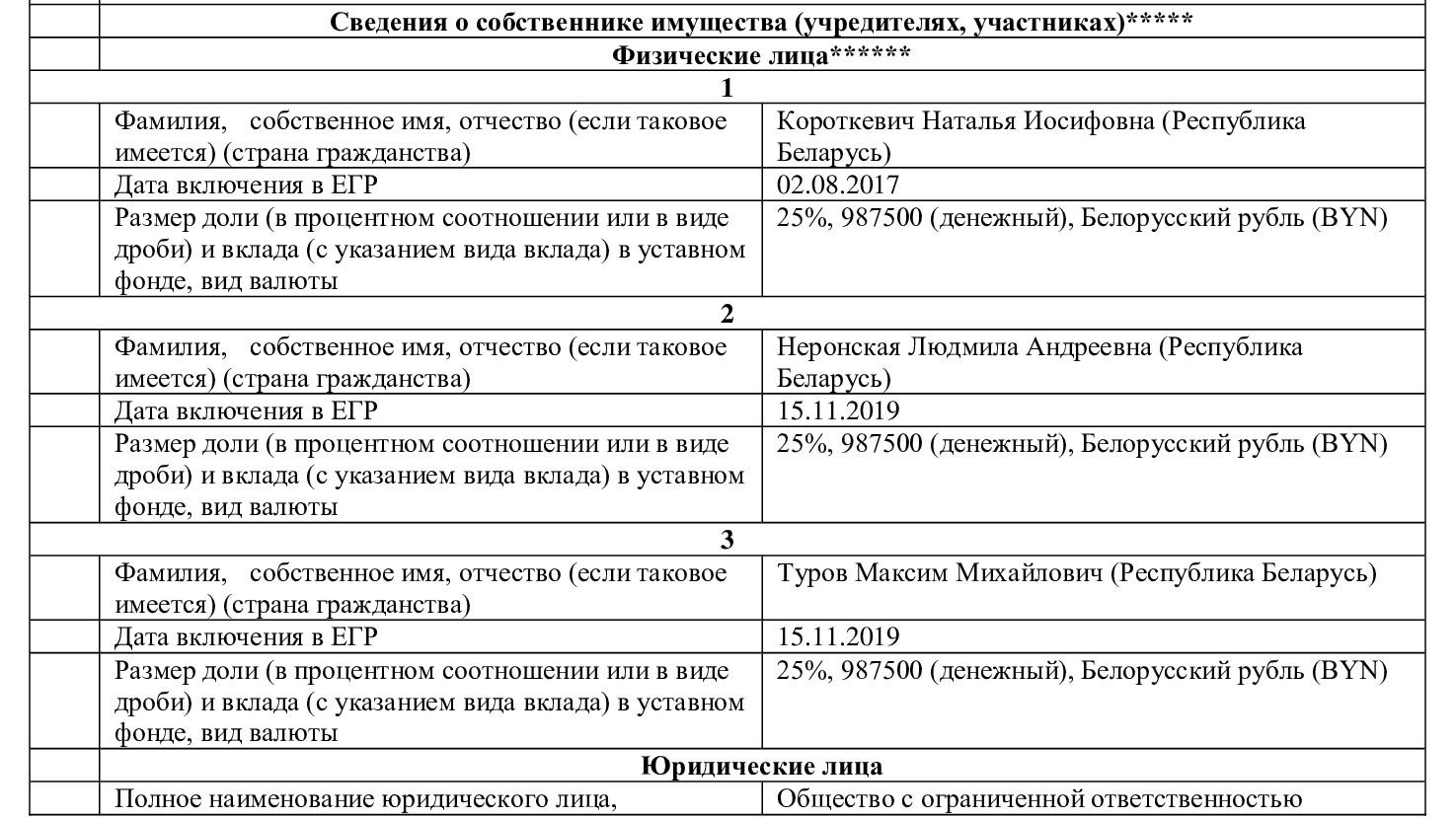

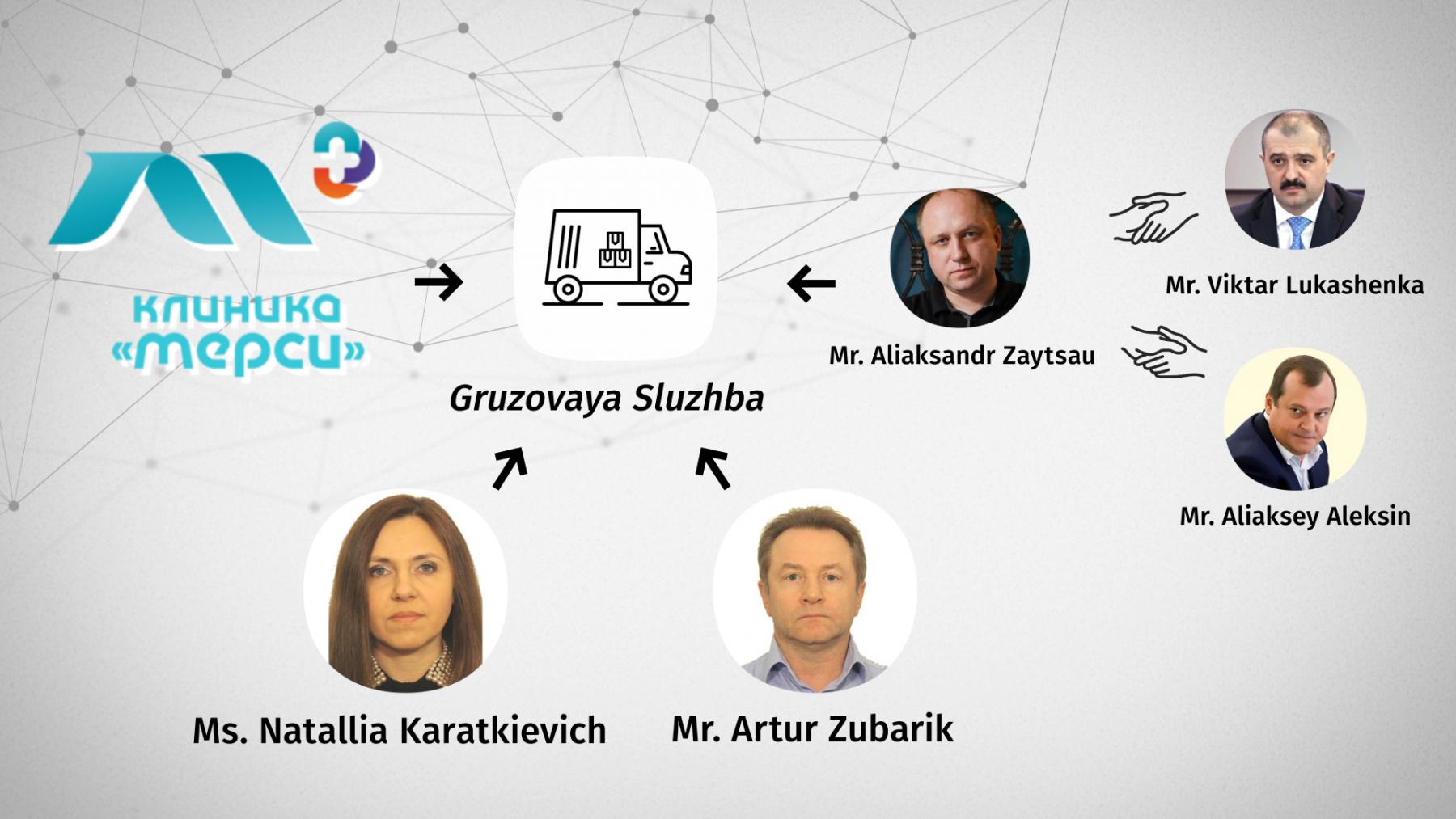

According to state documents, Merci is owned by three natural persons and one legal entity with 25 per cent share each.

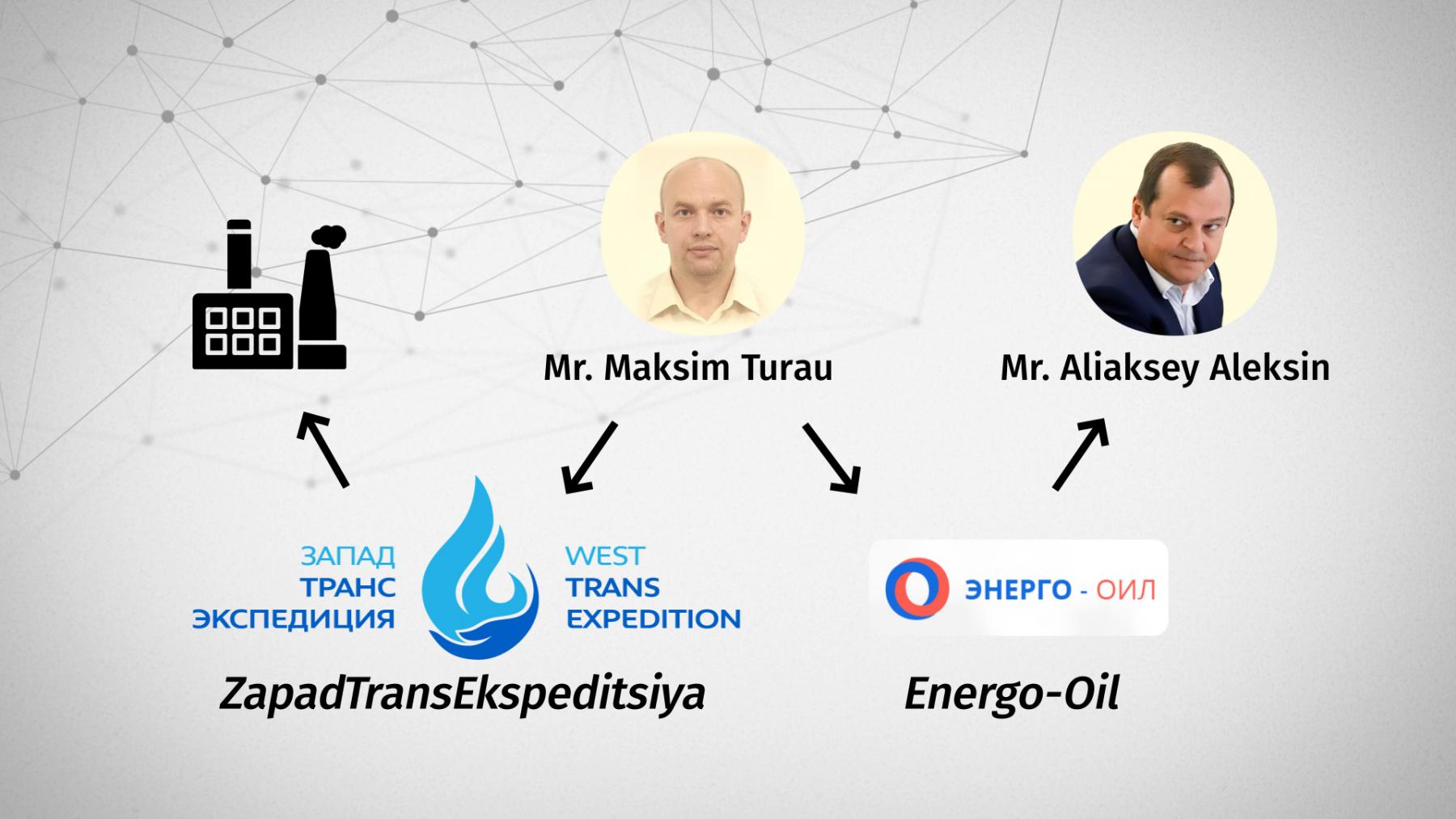

According to CyperPartisans, a Belarusian pro-democracy hacker group, the first listed person is Mr. Maxim Turov who used to work at Zapadtransekspeditsiya (owner of a gas treatment plant near Brest) after working at Energo-Oil that is controlled by Mr. Aliaksei Aleksin, also known as the ‘tobacco king of Belarus’. Mr. Aleksin is known to have close ties with Mr. Aleksandr Lukashenko and has entered EU sanctions lists for being Mr. Lukashenka’s moneyman.

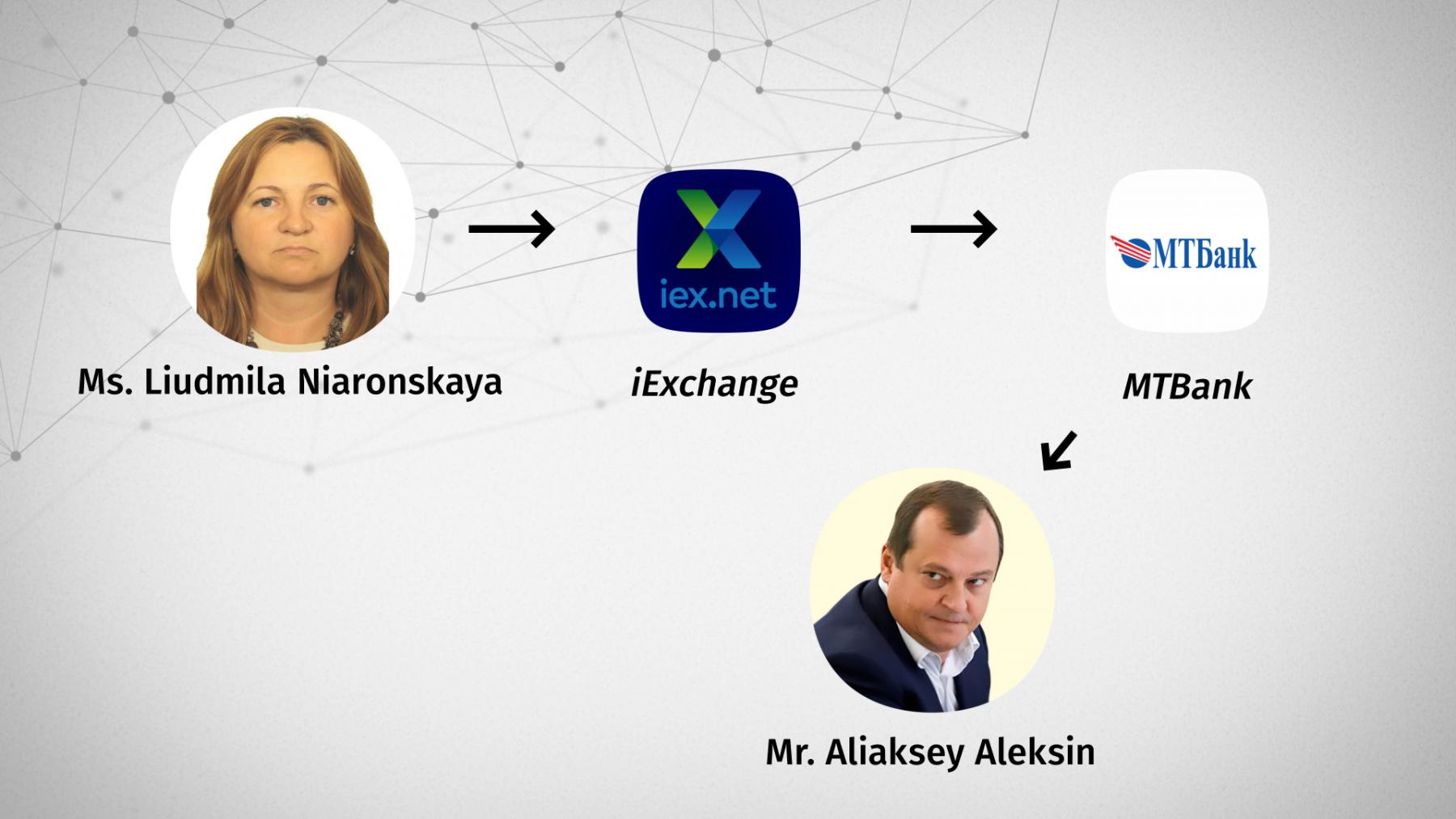

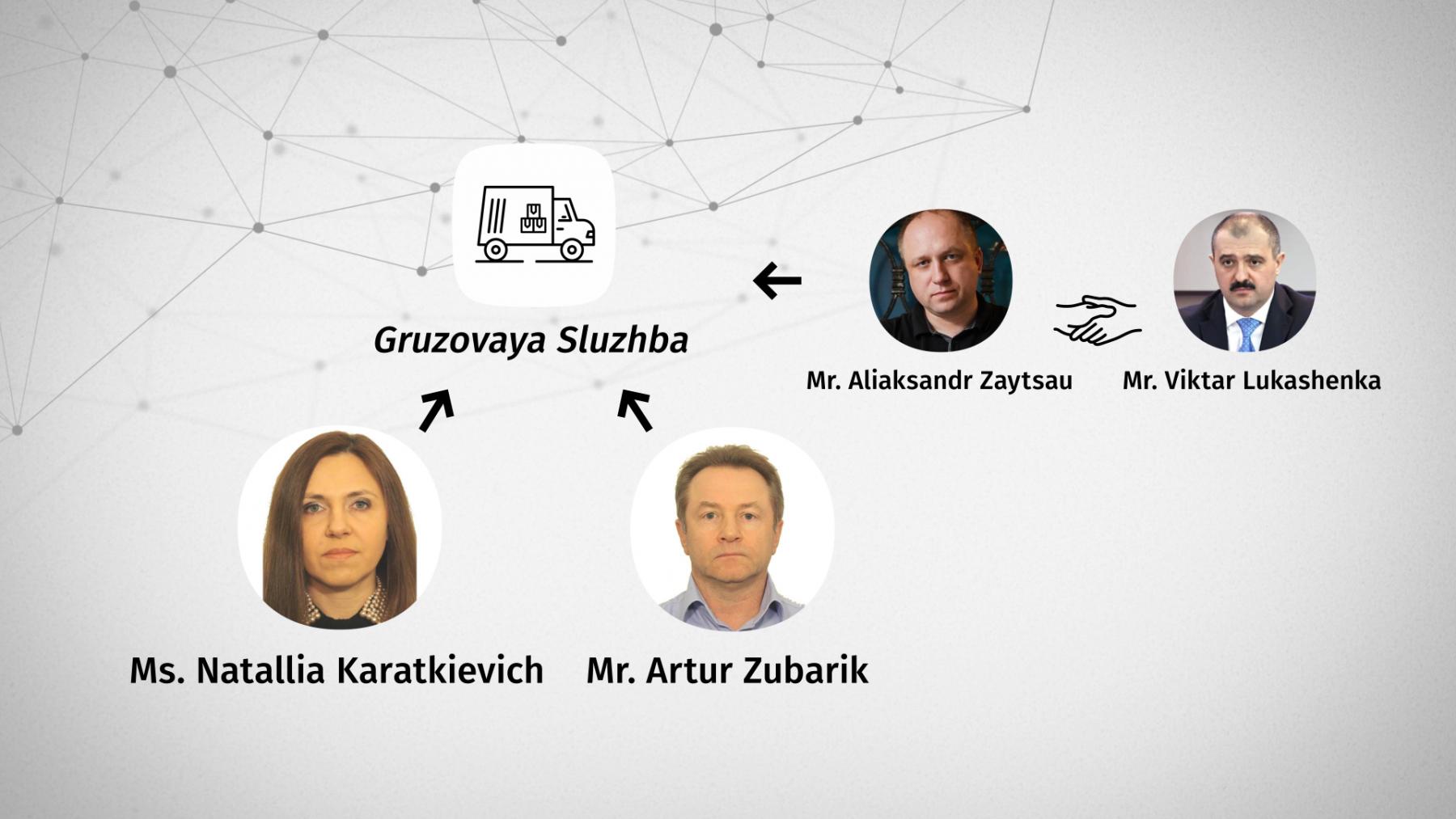

Merci’s second owner is Ms. Liudmila Niaronskaya who has stakes in companies affiliated with Mr. Artur Zubarik – Transekspeditsiya, Zapadtransekspeditsiya, Gruzovaya Sluzhba-Zapad, GazEnergyKhim, and Syrjevyje resursy-Bel.

At some point Ms. Niaronskaya had a stake at iExchange, the first Belarusian crypto currency exchange that partnered with MTBank.

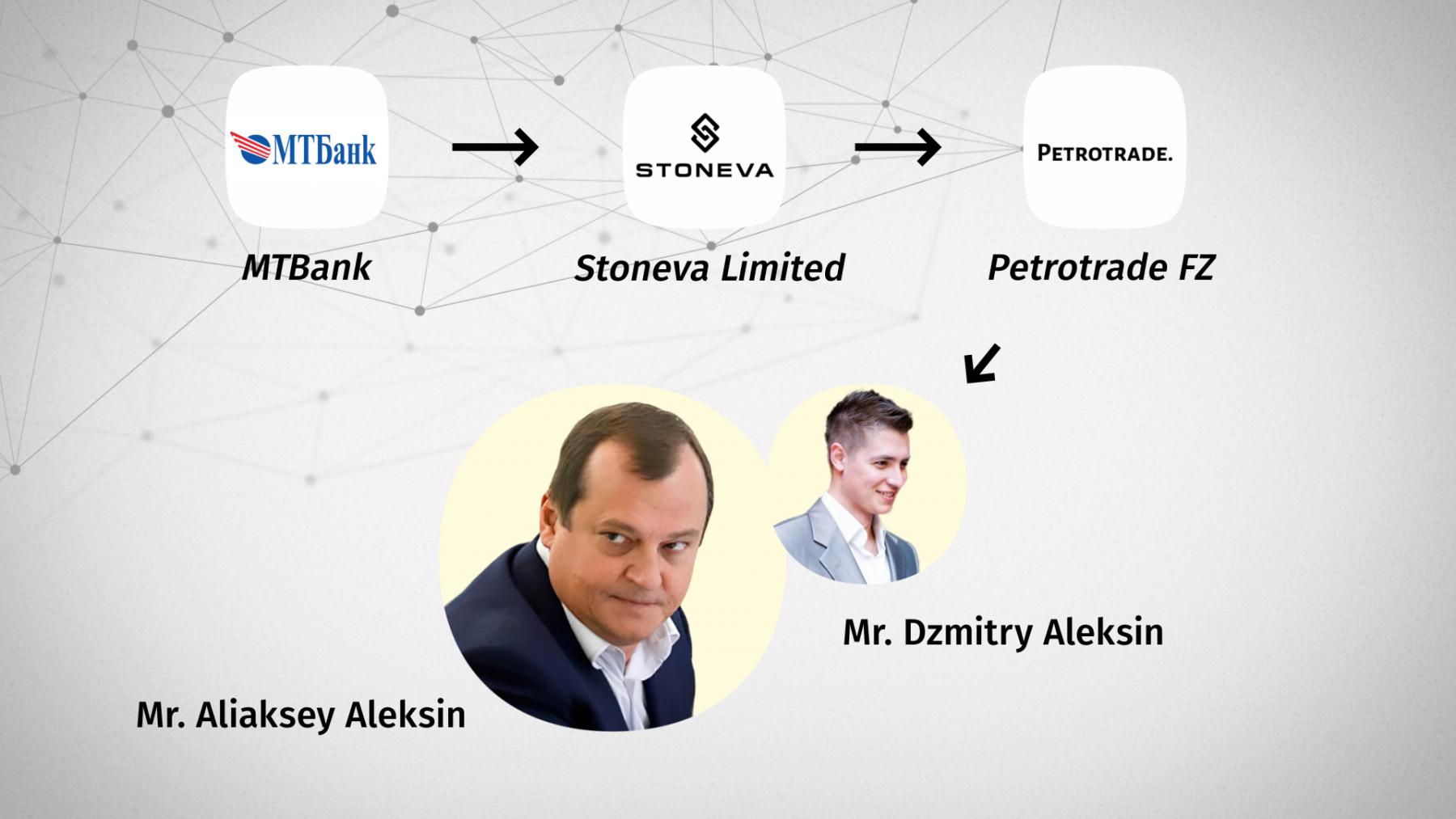

Mr. Aleksin was listed as the bank’s legal owner until the EU imposed sanctions on him. Following that, the bank’s ownership changed to Stoneva Limited – an Emirates company formally owned by a Lebanon citizen Mr. Abdo Romeo Abdo who has been living in Belarus since 1994. Incidentally, Stoneva Limited is registered under the same address as Petrotrade FZ owned by Mr. Aleksin’s son Dzmitry.

The third owner is Ms. Natallia Karatkevich who was listed as a co-owner of Gruzovaya Sluzhba last year. According to CyberPartisans, she used to be the wife of Mr. Zubarik (mentioned above).

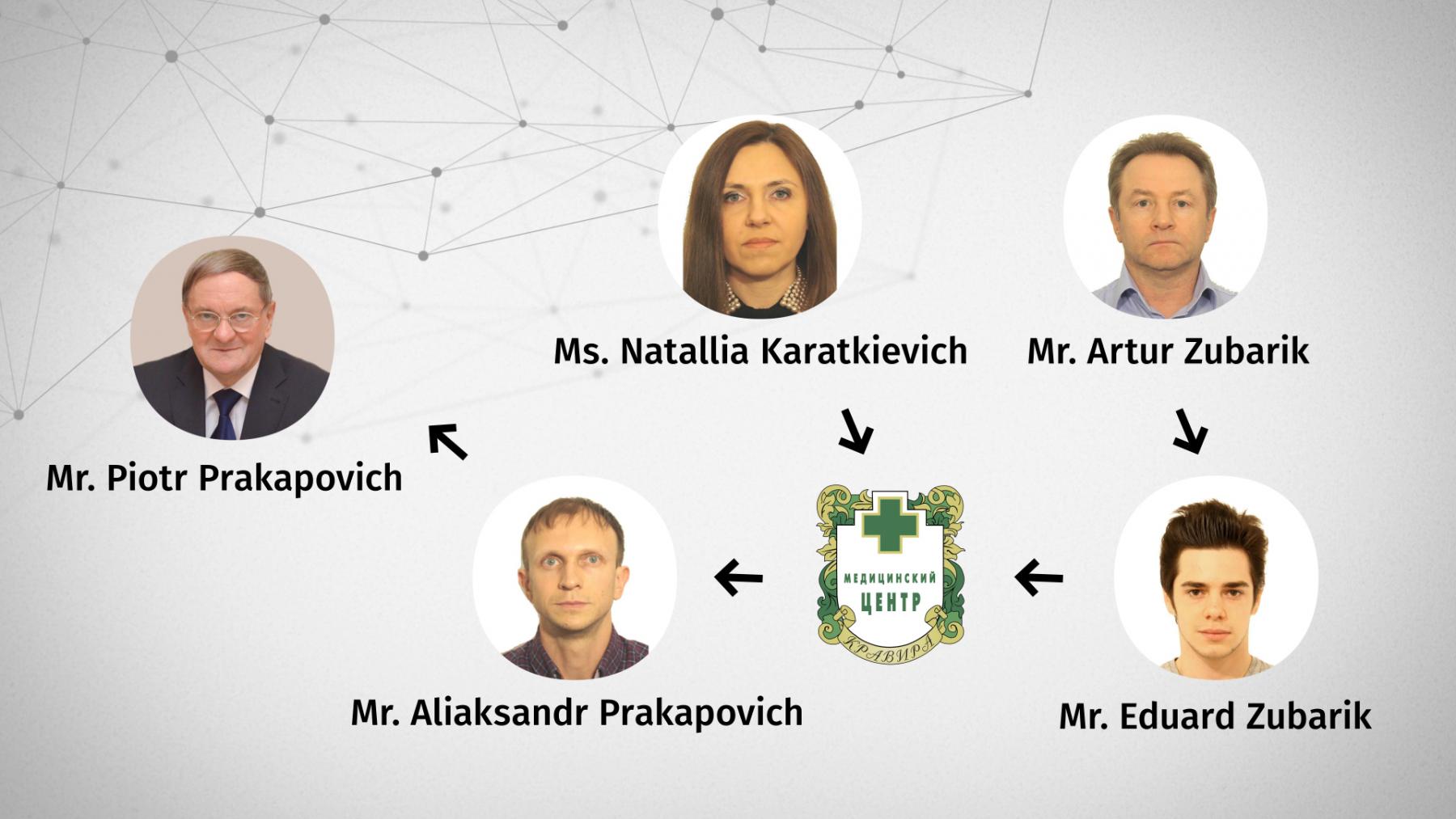

Prior to becoming involved in Merci, Ms. Karatkievich and Mr. Pyotr Prakapovich’s son used to own Kravira, a medical practice in Minsk before parting ways five years ago due to disagreements (Mr. Pyotr Prakapovich is the ex-head of the National Bank of Belarus).

Merci’s fourth owner is Gruzovaya Sluzhba – a firm that once had the most railway carriages on its books in the country. At present, the company is largely owned by Mr. Zubarik. But in 2013-2015 its co-owner was Mr. Alexander Zaytsev, Mr. Viktor Lukashenko’s aide.

According to Mr. Zubarik, Mr. Zaytsau sold his share “because he wanted to have his own logistics business”. Despite this, Merci and ZapadTransEkspeditsiya became sponsors of FC Rukh oversighted by Mr. Zaytsau.

Mr. Zubarik has denied Viktor Lukashenko’s involvement in Merci:

“This is a lie. Don’t trust anyone who spreads these rumours – said the businessman before adding that he wasn’t acquainted with Viktor Lukashenko although he knows who he is”.

Funding for the construction and fit out of Merci came from a joint Belarus Development Bank and World Bank program supporting small- and medium-sized businesses in Belarus. According to Mr. Zubarik, the money was up for grabs for “anyone who could write and defend a business plan”.

Mr. Zubarik is mostly known for his involvement in processing and transportation of propane and butane liquefied petroleum gas (LPG). The media used to accuse him of reexporting Russian LPG to Poland and Ukraine through Belarus – allegations which he would deny by saying that “no reexportation took place in the legal sense” because there are no customs borders between the Eurasian Economic Union member states. “We would simply purchase [the LPG in Russia and Kazakhstan] and sell it to [Poland and Ukraine]” – said the businessman. According to him, this business is no longer operating due to sanctions and the war in Ukraine.

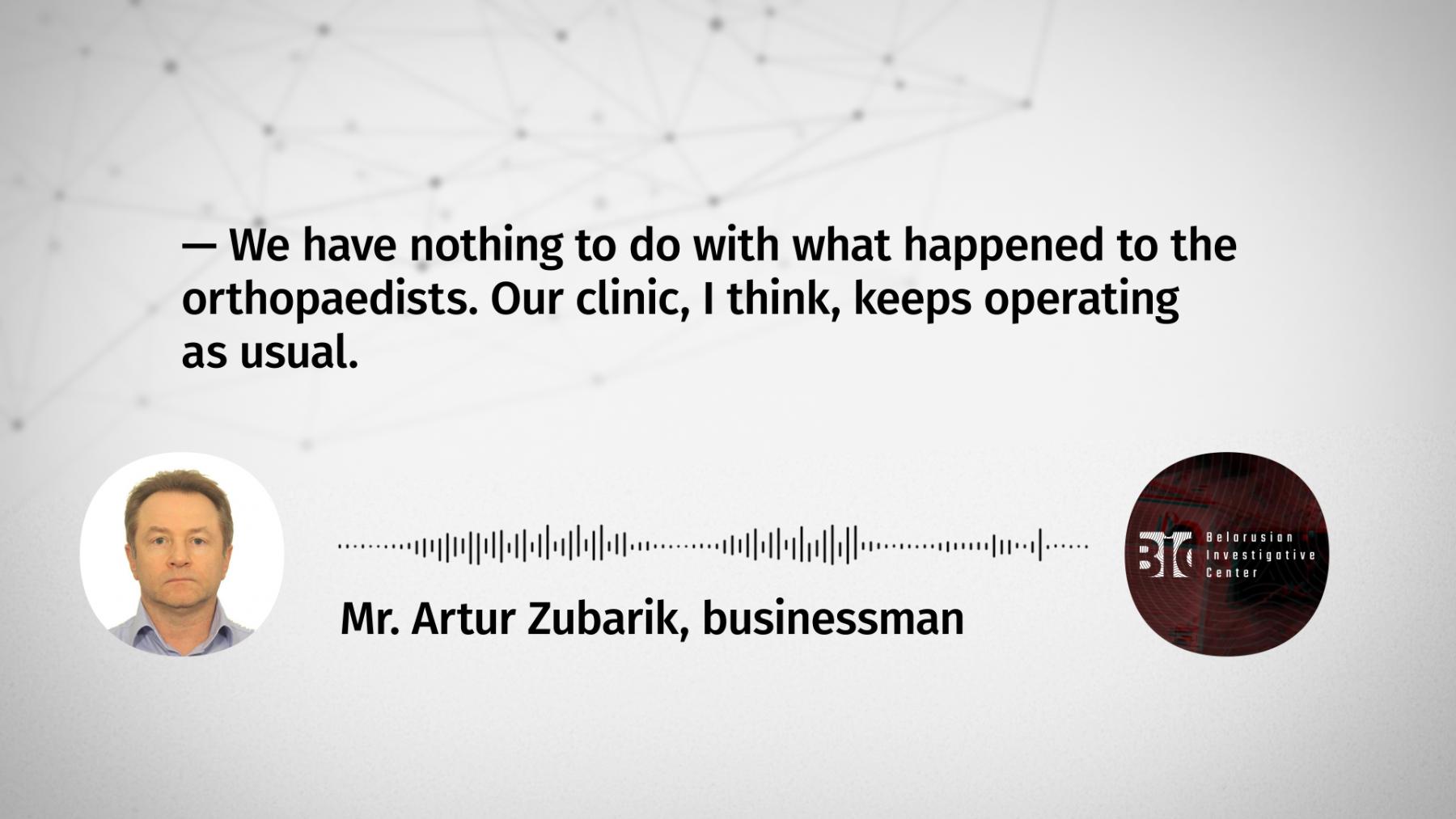

Mr. Zubarik has denied day-to-day involvement in the business and was adamant that the Clinic had nothing to do with the ‘case of orthopaedics’.

Ms. Karatkievich has not answered our phone calls.