This text was prepared in partnership with the Rabochy Ruch initiative and the Siena Lithuanian investigations centre with the support of the CyberPartisans hacker group.

Grodno Azot circumvents European sanctions by using straw companies. Supported by its partners, BIC identified two such firms. One of them transports fertilizers on trucks, the other one uses rail. Belarus president Aleksandr Lukashenko’s “money bags'' are among multiple beneficiaries of these schemes.

Belarusian authorities are directly involved: one of the straw companies has been set up by the Hrodna District Executive Committee. The scheme also involves ghost companies and structures that were used to siphon money from Belaruskali.

Bypassing sanctions, the chain of companies enabling European money to fill the pockets of Belarusian officials weakens the EU’s ability to put pressure on the Belarusian regime. As a result, the EU has less leverage of influence to get the release of political prisoners in Belarus, including former Grodno Azot workers.

Ambush on the border

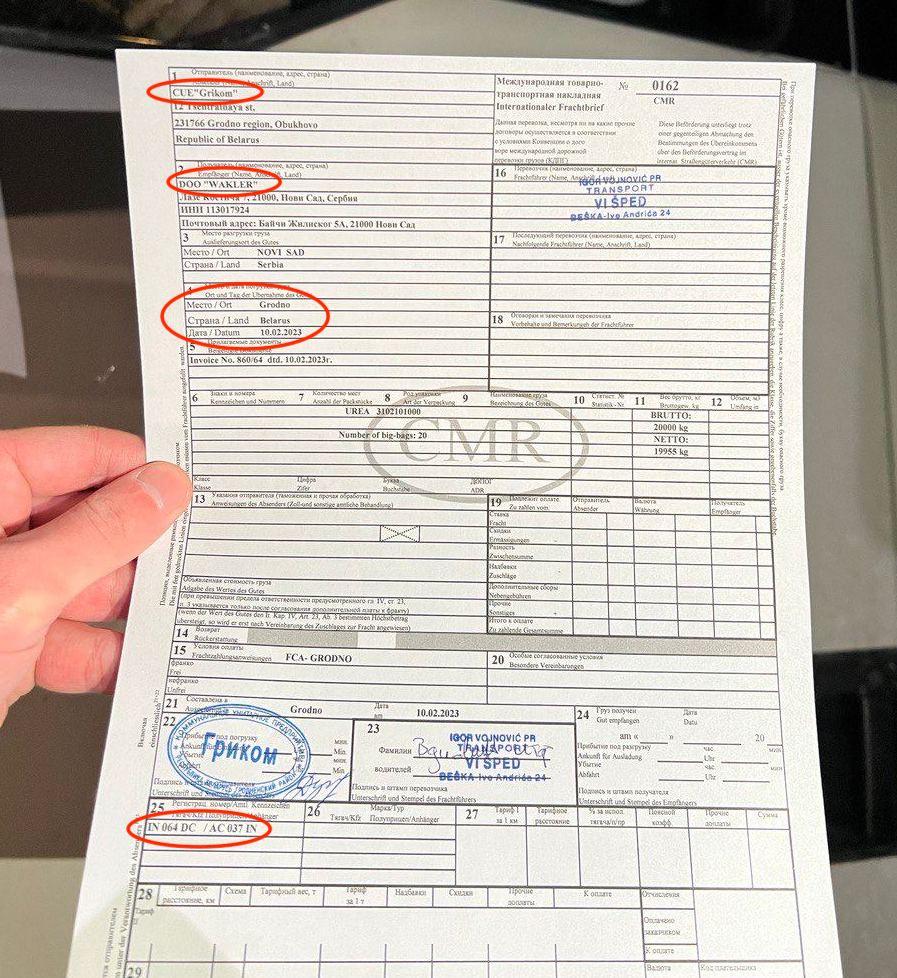

The night of February 13-14 at the Lithuanian border was turbulent. Activists of the Rabochy Ruch (Workers’ Movement) ambush Belarusian trucks loaded with sanctioned products. The first truck passes through Lithuanian customs late at night, but it is blocked by the activists. The driver, visibly confused, presented documents showing the truck transports fertilizers from the sanctioned Grodno Azot company into Europe.

Stanislau Ivashkevich, the head of the Belarusian Investigative Centre, covers the action as a correspondent. He succeeds in talking to the truck driver who confirms that the truck was loaded at Grodno Azot. About an hour later the activists blocked another truck. Its driver also confirms that he transports Grodno Azot fertilizers.

Lithuanian police and border patrol arrive and ask the activists to stop the blockade, but they refuse. Some time after midnight customs officers arrive, and the two intercepted trucks are taken for additional inspection. The next day, Lithuanian customs begins an internal check of possible violation of international sanctions.

The same morning, Grodno Azot executives gather for a meeting that drags on for several hours. BIC journalists manage to get the plant’s general director Igor Lyashenko on the line, but he refuses to discuss the interception of trucks at the border or comment on documents we possess that shed light on the schemes used by Grodno Azot to skirt sanctions.

Hrodna straw company

Viktar Rusak has worked for Grodno Azot for more than 30 years. He held different positions from foreman to the head of the social development department. From 2016-2019, he also served as a member of the House of Representatives. In the 2020 presidential election, he headed the election commission at a polling station located within the Grodno Azot dormitory.

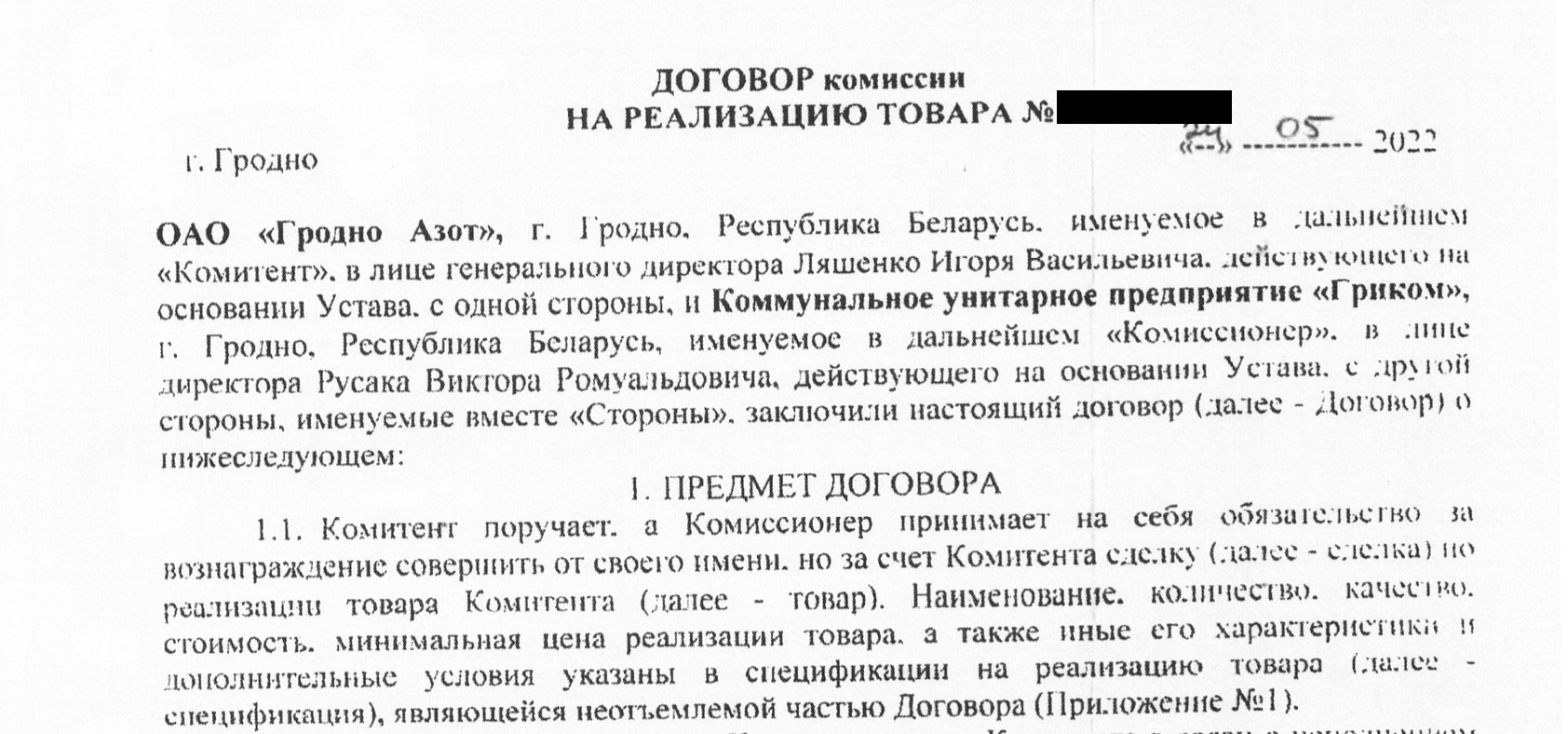

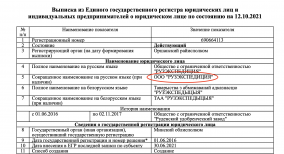

In July 2021, Rusak was appointed as director of Grikom, a company founded the day before. It is owned by the Hrodna Executive Committee.

It was Grikom that replaced the sanctioned Grodno Azot as a supplier of fertilizers to the West.

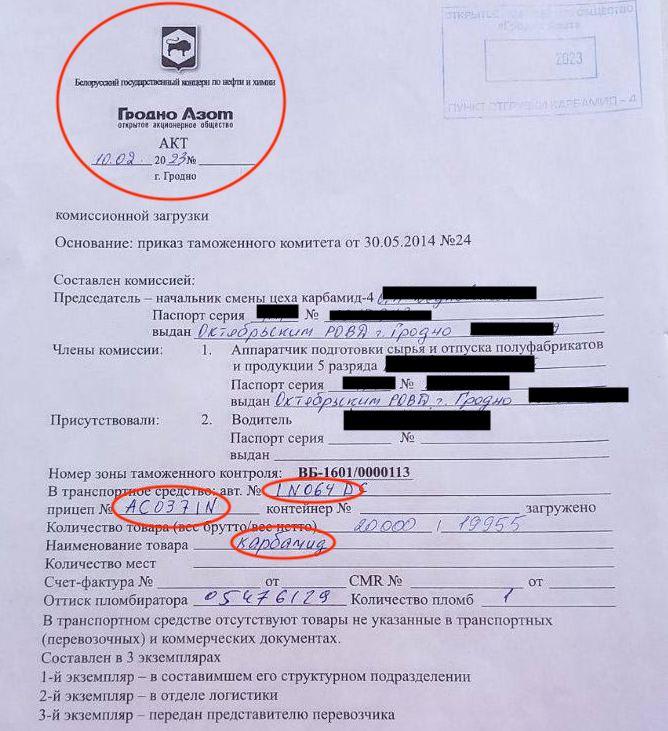

But only on paper, as the Rabochy Ruch activists found out after they obtained a loading report for one of the trucks they had stopped on the Lithuanian border. It is printed on Grodno Azot official template and clearly states that it was at that factory where the truck loaded carbamide. The report bears the seal of Grodno Azot.

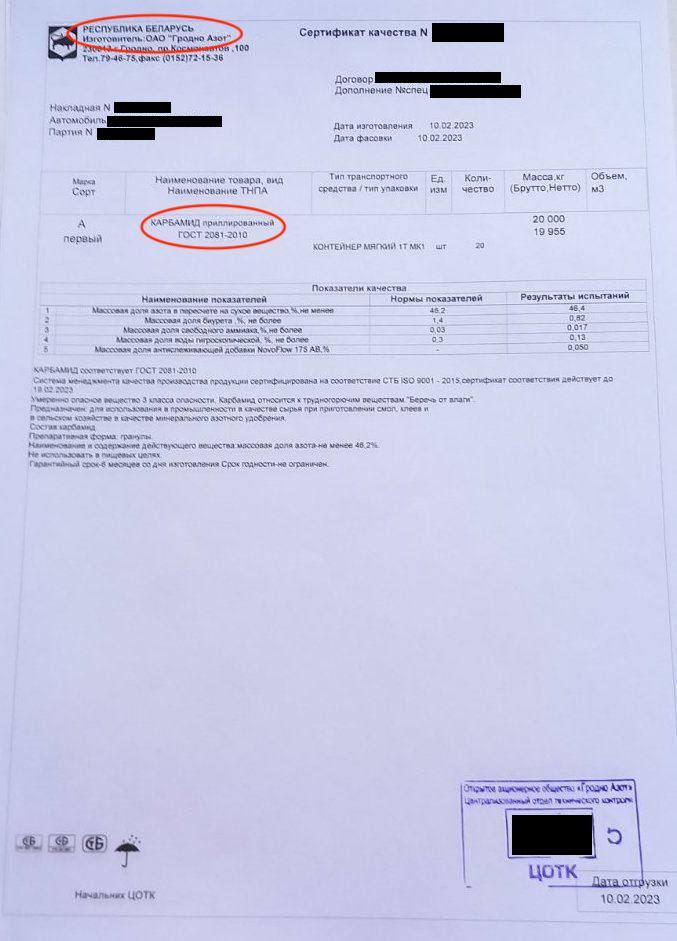

They also obtained a carbamide quality certificate that specifies Grodno Azot as the fertilizer manufacturer.

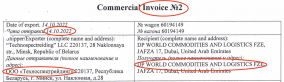

BIC also has a copy of a contract showing that Grikom undertakes to sell Grodno Azot products.

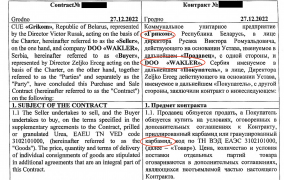

We also found a contract between Grikom and the Serbian company Wakler. It stipulates that Grikom shall supply about €20 million worth of carbamide to Serbia during one year.

At the same time, as we learned from the drivers that Serbian customers’ cars are loaded with fertilizers at Grodno Azot, and drivers sign on the company’s official letters. It should be noted that Serbia has joined the EU sanctions against Grodno Azot.

It was for the Serbian company Wakler that the trucks intercepted at the border were carrying carbamide. We asked Željko Erceg, the director and co-owner of Wakler, to comment. He claimed that he was not aware of it.

Grikom director Viktar Rusak refused to talk to us by phone. Rabochy Ruch’s sources reported that he signs documents drafted by Grodno Azot plant managers that help bypass sanctions. The employees also identify and negotiate with customers and offer them a scheme to skirt sanctions through Grikom, insiders told Rabochy Ruch.

This is just one of the straw companies Grodno Azot uses to continue deliveries to Europe. As we found out together with the Lithuanian investigation centre Siena, the main grey fertilizer export routes from Belarus are by rail and sea.

Dubai offshore

On the shores of the Persian Gulf lies Dubai, the Middle East’s largest commercial and financial centre. The emirate is renowned for its Free Economic Zones and simplified taxation, making it one of the Top-3 re-export centers in the world. It is here, next to the largest port in the Gulf, that Dubai’s port operator DP World has its headquarters. It is part of Dubai World, a holding company owned by the Emirate of Dubai government.

In May 2016, Belarus president Lukashenko met with DP World CEO Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem. Lukashenko then declared he was looking forward to implementing joint logistics projects with the UAE.

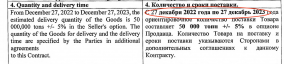

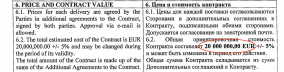

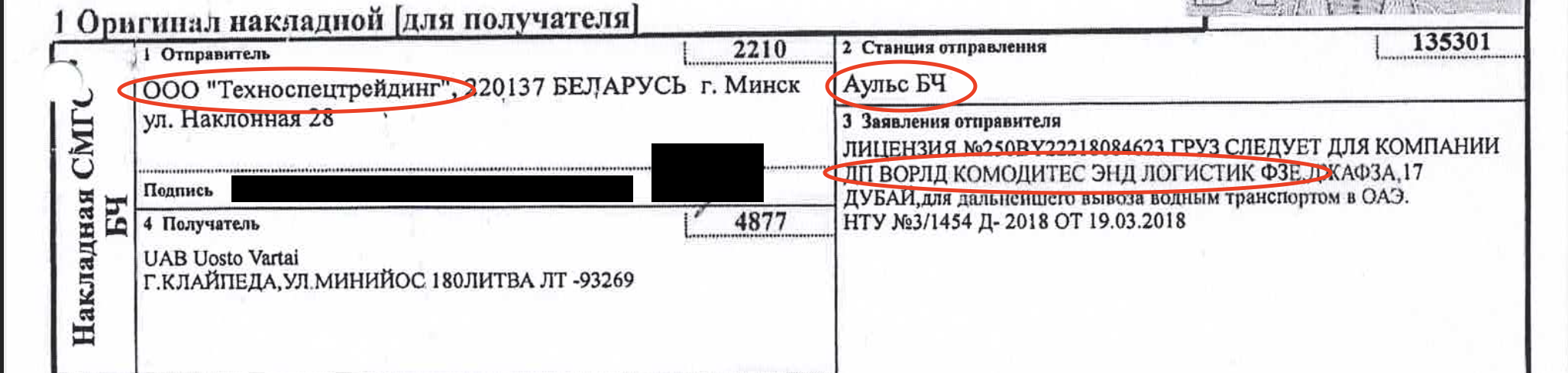

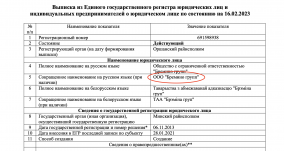

In October 2022, the story of this cooperation took an unexpected turn. The Belarus Ministry of Antimonopoly Regulation and Trade granted a one-time export license to supply carbamide to the little-known Belarusian company Technospectreiding. The buyer was the Emirati firm DP World Commodities and Logistics FZE, sharing the registration address with the DP World head office. Our colleagues from Siena found documents showing that Technospectreiding was planning to supply 30,000 tonnes of carbamide to the Emirates worth €15 million.

The copies of cargo documents in our possession helped us precisely trace the delivery route of this fertilizer and find evidence of sanctions evasion. Along the way, we found regular subjects of our previous investigations.

We studied the quality certificate that Technospectreiding used to supply carbamide to Dubai. The fertilizer meets the GOST 2081-2010 standard.

The same product is manufactured in Belarus only by Grodno Azot. This is confirmed by two independent sources – Yury Ravavy, a former Grodno Azot worker who headed the plant strike committee, and Arminas Kildišis, a Lithuanian fertilizer expert.

Technospectreiding claims to be both a supplier and producer of carbamide.. Such large-scale projects in Belarus are announced years in advance. There was no such public information. But there were reports that the Belarusian authorities were going to increase the capacity of the Grodno Azot ammonia shops (from which carbamide is produced) despite sanctions. The modernization project was estimated at $270 million.

We visited Technospectreiding headquarters to seek official commentary. We expected to see large production, taking into account the company’s international contracts. But its office turned out to be registered in an ordinary cottage in a residential suburb of Minsk. There was no trace of any carbamide production.

But a further search for connections between Technospectreiding and Grodno Azot yielded interesting results. The carbamide allegedly produced by Technospectreiding was loaded into railcars at the Auls railway station next to Grodno Azot.

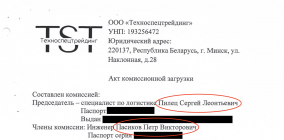

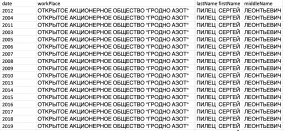

Overlaps were also found in the staff of the two companies. With the help of the CyberPartisans hacker group, we found out that Technospectreiding logistics specialist Siarhei Pilets and an engineer, Petr Pasikau, used to work at Grodno Azot.

These facts suggest that Technospectreiding is another straw company of Grodno Azot. It might be used for supplying products to Europe to circumvent sanctions, and the Emirati buyers might just be a cover.

“As far as I know, the Emirates and the neighboring countries have enough gas to export carbamide themselves. I think purchasing it from Belarus would be somewhat illogical. Carbamide is exported to countries where ammonium nitrate and calcium ammonium nitrate are not used. These are mainly France and Germany,” fertilizer expert Arminas Kildišis commented.

Our fellow investigators at Siena contacted Technospectreiding owner Dmitriy Goshko, but he declined to comment.

Ghost companies

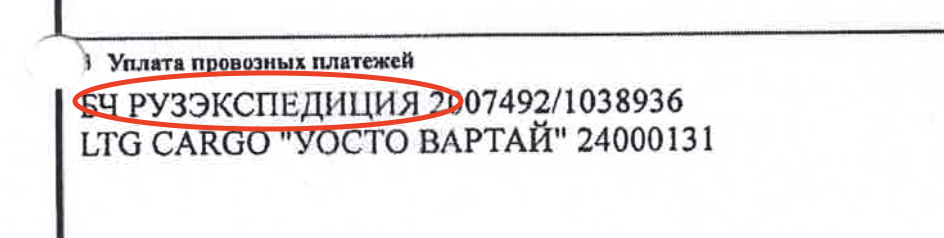

From the Technospectreiding consignment documents, we learned that RuzSpedition acted as a forwarder for the Dubai carbamide shipment.

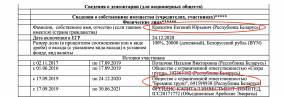

It is registered in the Bremino-Orsha special economic zone and is exempt from some taxes. The firm was previously owned by the Bremino Group logistics company that belongs to Aliaksei Aleksin, Mikalai Varabei and Alexander Zaytsev. All of them are under EU sanctions as Lukashenko’s money bags. RuzSpedition itself got around the restrictions. In 2020, Yauheni Krakhotsin, Zaytsev’s proxy, took over ownership.

What also drew our attention in the carbamide supply chain was the Lithuanian importer of the cargo – Rogera, a firm registered in Kaunas.

Our colleague Šarūnas Černiauskas from the Siena investigations centre visited the company’s registration address and found only a garage. The owner of Rogera has not contacted us back.

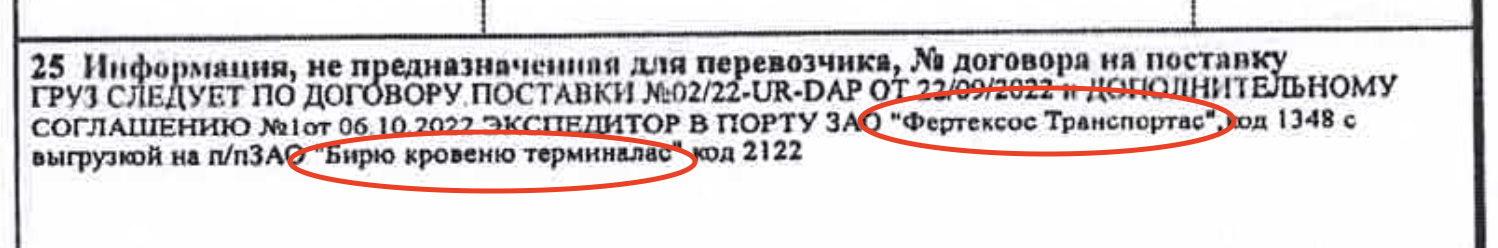

However, Ferteksos Transportas, which handled the Technospectreiding shipment to Dubai, is much more familiar. This company is a part of the scheme to siphon money from Belaruskali, which we disclosed in one of our investigations. The main stopover in that story – the BKT terminal – was also a stop in the shipping chain of carbamide shipments to the UAE.

BKT representatives assured us that all cargo handled at the terminal is checked by Lithuanian state authorities, and the company fully trusts their competence. BKT also claims it has no relations with Grodno Azot, Technospectreiding or Rogera.

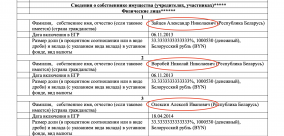

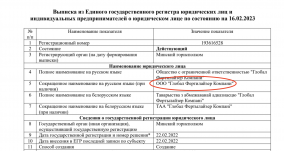

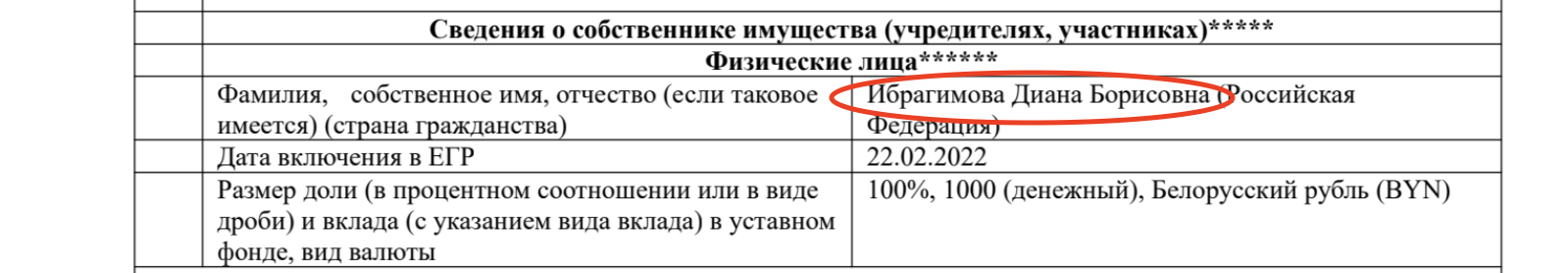

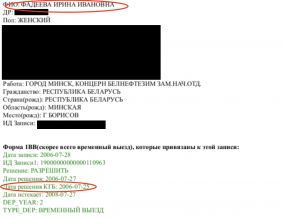

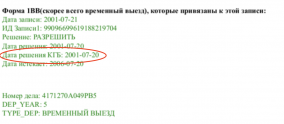

We also looked closely at the owner of the railcars transporting the carbamide – the Global Fertilizer Company, registered in Belarus but founded by Russian national Diana Ibragimova. In a telephone conversation, she claimed to have a vague idea about the company and redirected us to a person who actually runs the business, Iryna Fadzeyava.

Fadzeyava used to work for the Belneftekhim concern of which Grodno Azot is a part. In 2001-2008, the KGB issued a special permit to leave the country in her name. This might indicate her access to sensitive information related to national security. In a conversation with us, Fadzeyava said that, as a lawyer, she had helped Global Fertilizer Company with registration, but did not know the firm’s dealings.

Backed by our colleagues from the Siena investigations centre, we handed these materials over to Marius Skuodis, the Lithuanian Minister of Transport and Communications. He promised to look into these shipments:

“Judging by the information you’ve provided, it looks like some scheme. Because it’s very clear where the cargo is coming from and who the producer is. I will shortly receive other documents. I am going to petition state agencies – both the prosecutor’s office and the financial crime investigation service – to look into [the situation].”

To stop the illegal supplies, Lithuanian Railways suggests that sanctions should be imposed not only on Grodno Azot as a fertilizer producer, but also on its products.

Leverage

Grodno Azot fell under EU sanctions in December 2021 for firing and intimidating workers who participated in protests after the 2020 presidential election. In their statement, the European authorities noted that Grodno Azot was “responsible for the repression of civil society”.

After the August 2020 elections, Grodno Azot workers demanded their bosses publicly acknowledge election fraud and threatened to shut down the company. The police arrested 28 activists, but the strikes did not stop. The workers also joined a nationwide strike on October 26, 2020. About a hundred people gathered at the gatehouse, 32 of whom were arrested by riot police. According to media reports, some were beaten up in police vans.

After that, Grodno Azot activists came under pressure from the company’s management and investigative bodies: some workers were fired, and others were arrested. Six former Grodno Azot workers remain behind bars.

The Rabochy Ruch activists hope that sanctions against the company force Belarusian authorities to stop repressions against the plant workers. However, as long as Grodno Azot manages to circumvent the restrictions, the pressure may not be enough.

“Former employees of Grodno Azot are considered as political prisoners. They are deprived of the right to correspond, various punishments are applied to them, they are periodically sent to a punishment cell. The conditions are inhuman. And all their [former employees’ of Grodno Azot] loved ones are under control. They are controlled, monitored and exert psychological pressure. Many of them [former employees of Grodno Azot] have children, wives, parents. All of them have a very hard time,” said Aliaksandr Sakalou, a representative of the Rabochy Ruch initiative.

Meanwhile, Belarusian authorities keep handing down heavy sentences to workers’ movement participants. Andrei Khanevich, a father of three who worked as an equipment operator and led an independent trade union during the protests, received five years of imprisonment. He was convicted for talking to a Belsat TV journalist.

Former Grodno Azot worker Eduard Isayeu got three and a half years in jail for liking a post with an image of Lukashenko. His wife and small children are awaiting his release.

Three other workers, Uladzimir Zhurauka, Siarhei Shelest and Andrei Paheryla, are defendants in the Rabochy Ruch case. They have been kept in the Homel detention facility for over 16 months. Belarusian authorities sentenced them from 14 to 15 years in penal colony. Human rights organizations recognized them as political prisoners.