Spouses Eduard and Elena Apsit have established cleaning businesses in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. In Belarus, they made their money by bribing officials and rigging tenders. According to BIC's estimates, the Apsits earned at least €50 million in Belarus between 2014 and 2023.

In Russia, companies connected with Apsits got into cahoots with Yevgeny Prigozhin’s structures, among others. They evaded heavy financial liability. In Ukraine, Belarusian cleaning companies were also involved in bid-rigging.

After the occupation of Crimea and the outbreak of war in Donbas, Belarusian cleaners continued to receive state contracts in Russia and Ukraine simultaneously. By 2019, Eduard Apsit had withdrawn from all his Ukrainian companies. Latvian investigators believe that the companies came under the control of his proxies.

According to Latvian investigating officers, Eduard Apsit laundered the money he earned in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine through a European bank. They have frozen €73 million from the accounts of companies associated with him.

This text was produced in collaboration with colleagues from Vazhnye Istorii (Russia), Slidstvo.info (Ukraine), Re:Baltica (Latvia), TV3 (Latvia) with the support of the hacker group CyberPartisans.

From monopolist to defendant in 30 years

A Latvian court is investigating a major financial scandal with a Belarusian link. The primary defendant in the case is businessman Eduard Apsit, a Belarusian national. Prosecutors have blocked €73 million rom the accounts of companies associated with him – the amount they laundered through fictitious contracts between themselves, according to investigators. The investigation alleges that Apsit earned the money in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine and then transferred it to the EU through the notorious ABLV Bank.

In 2018, the the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network announced that it planned to sanction the bank for money laundering. The schemes, for example, helped North Korea buy or export ballistic missiles. In 2022, charges were brought against ABLV Bank by Latvian prosecutors. Several key employees were suspected of laundering €2.1 billion of illicit money.

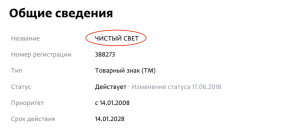

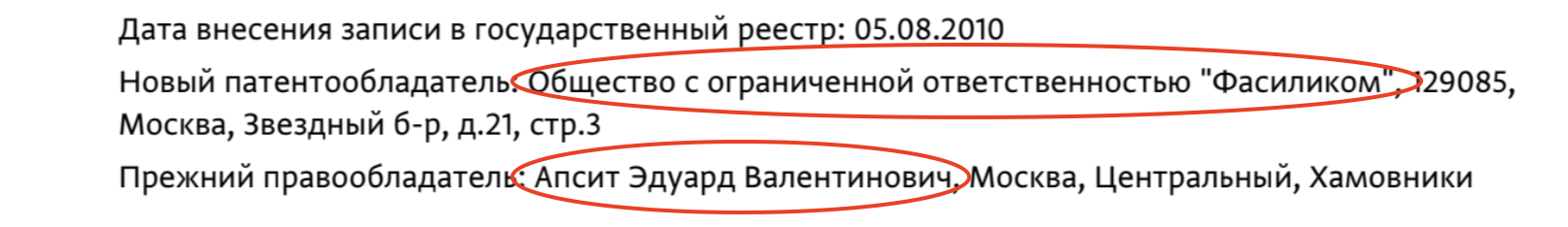

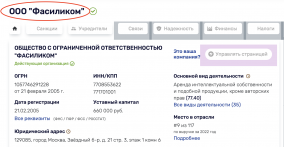

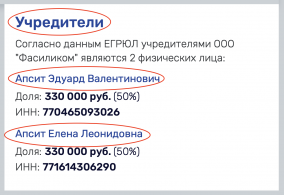

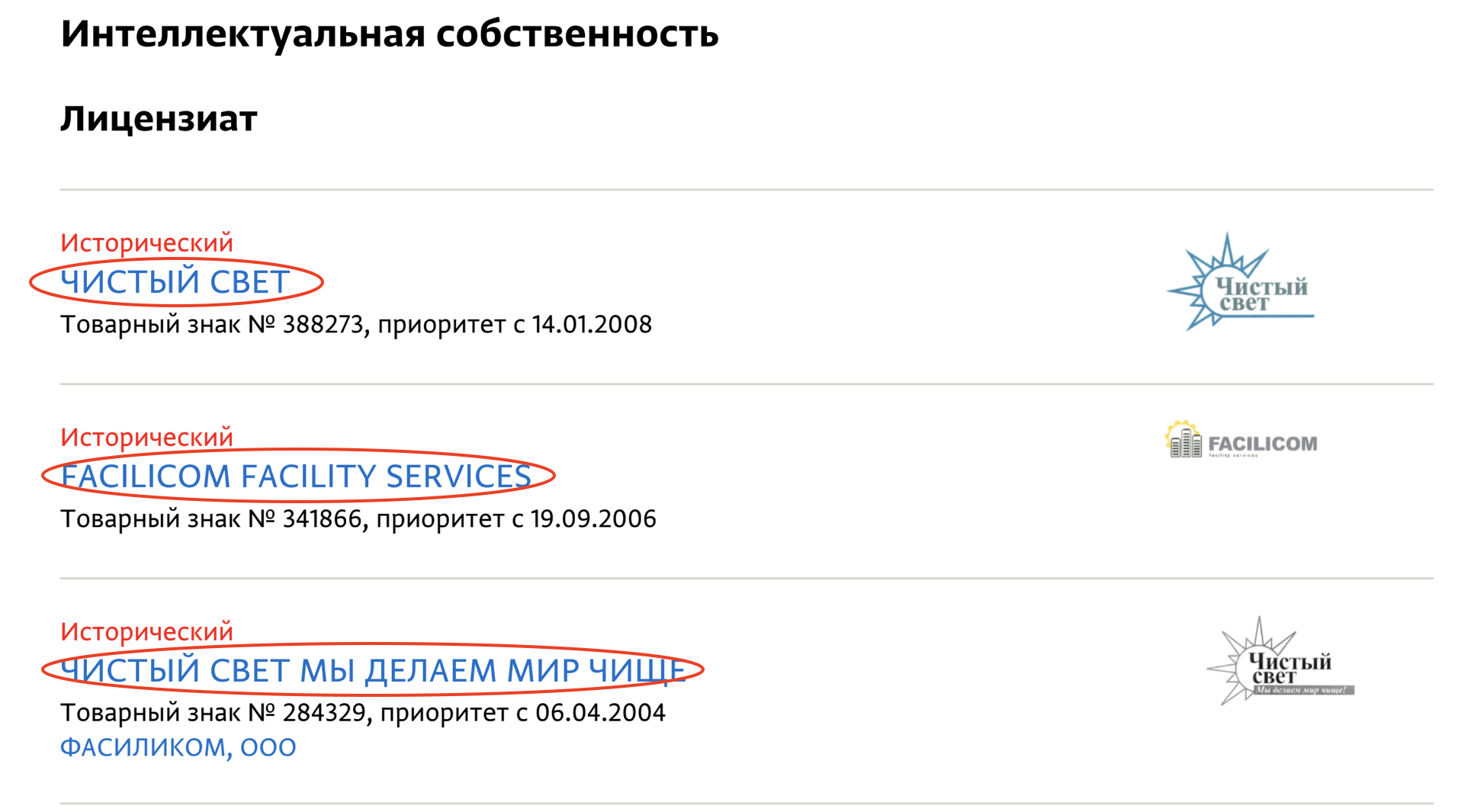

BIC investigated Eduard Apsit’s business history and found that the millions he is suspected of laundering in Latvia were made in Belarus and Russia under the brands Chisty Svet and Chisty Svet. My Delaem Mir Chische and in Ukraine through a group of cleaning companies called Chisto. He set up these businesses with his wife Alena.

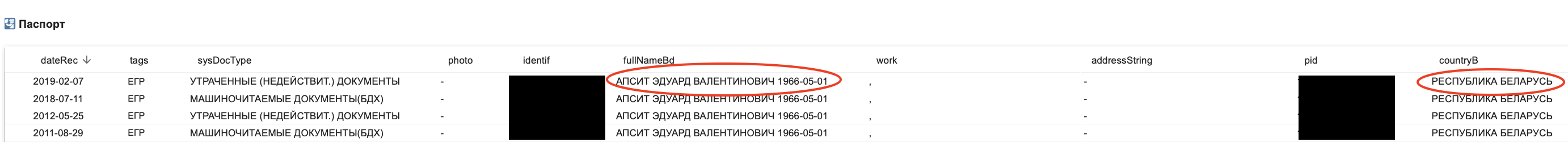

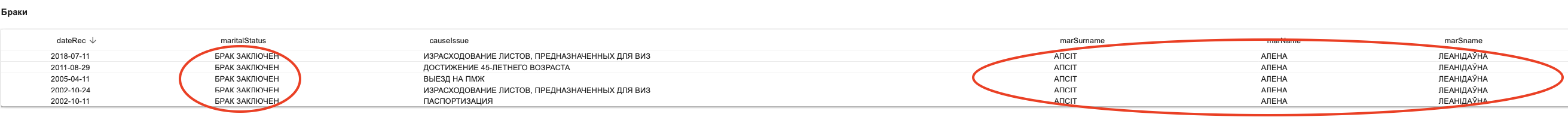

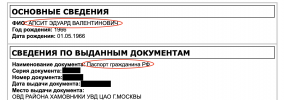

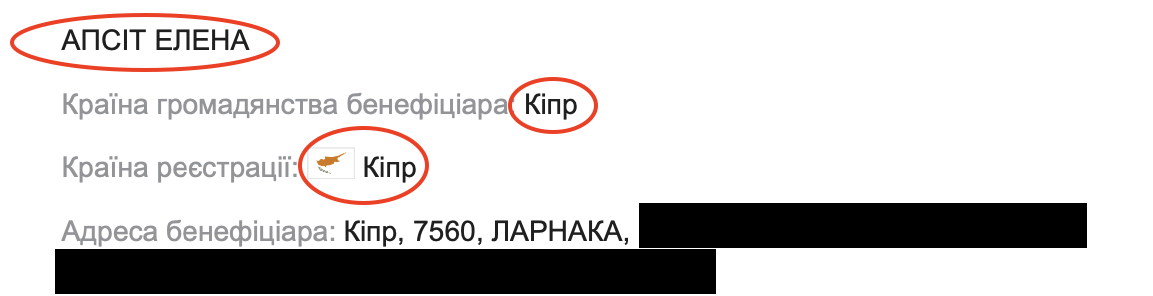

In addition to their Belarusian passports, the spouses are nationals of other states. He is also a Russian citizen, she is a Cypriot national.

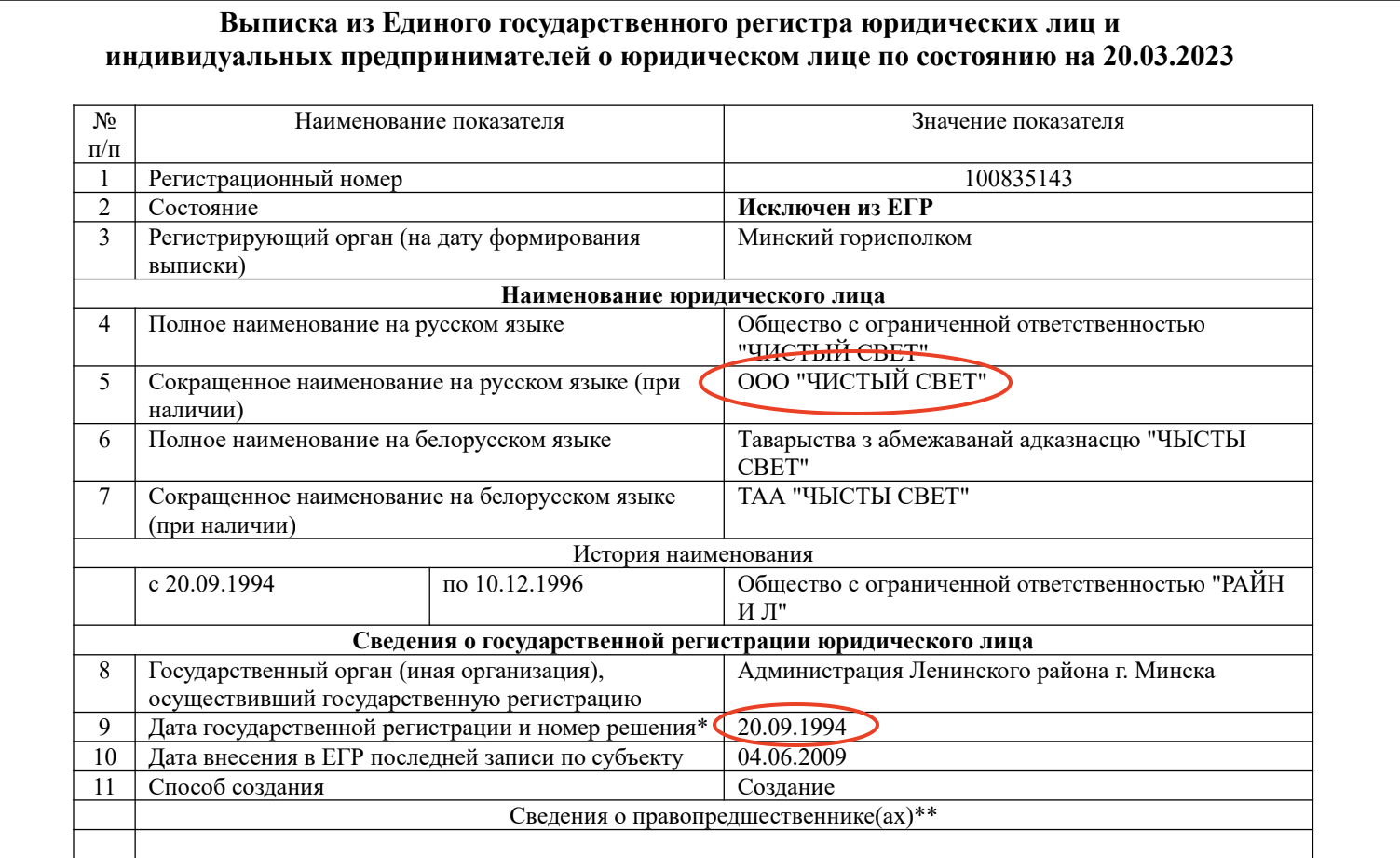

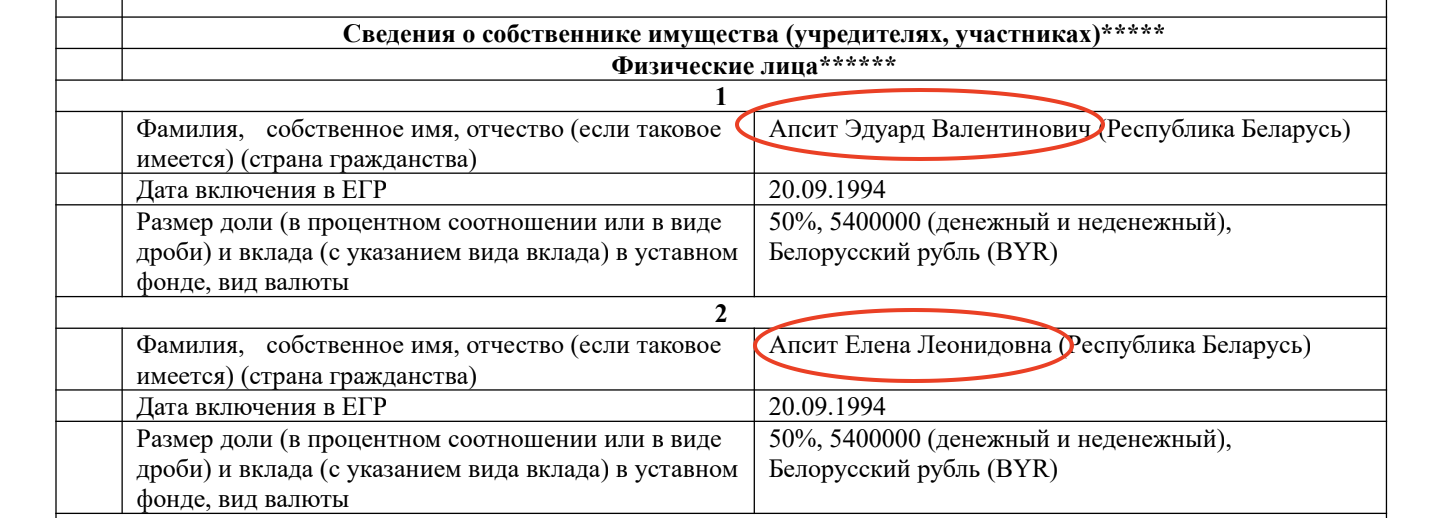

The Apsits started their business in 1994 in Minsk and for a long time were the only players in the Belarusian cleaning market.

Over the last 30 years, the couple opened ten companies. Currently, only two are active: Chisty Svet Plus and Upravlyayuschaya Kompaniya Fasilikom.

In 10 years of doing business in Belarus, they received hundreds of government contracts worth over €40 million at current exchange rates. Their clients include the presidential clinic, hospitals, universities, the National Library, Belteleradiocompany and Hi-Tech Park.

BIC investigated how Apsits' firms obtained such important and lucrative orders. We analysed the tenders won and found machinations.

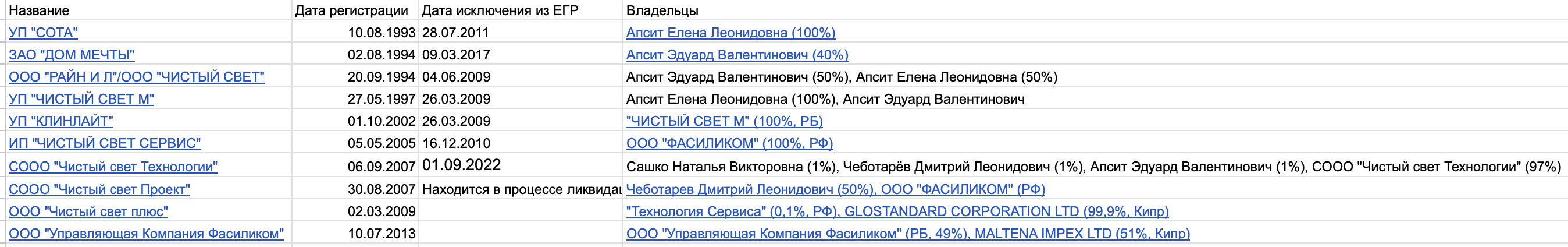

The case of the Presidential Medical Centre

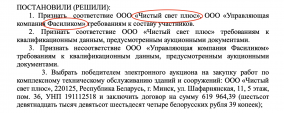

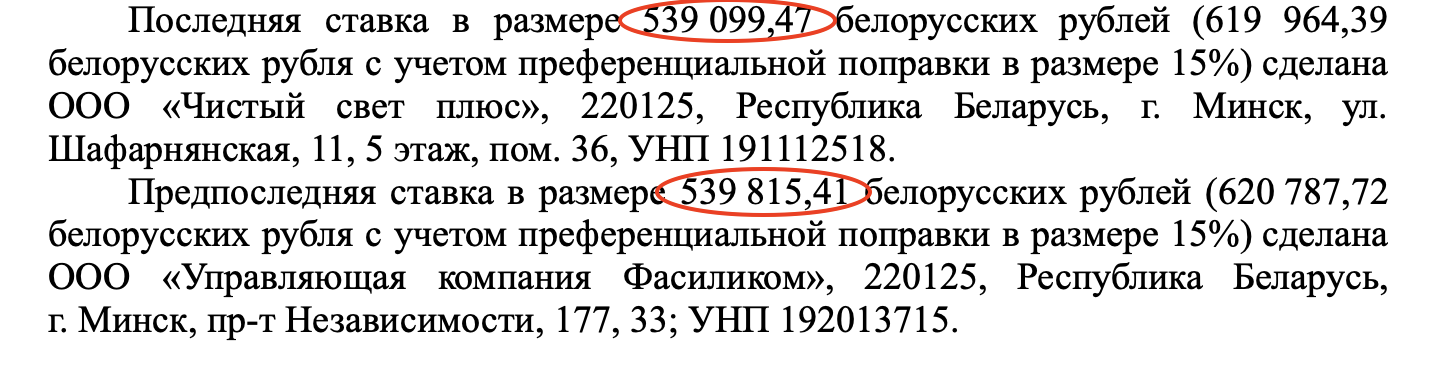

On 28 September 2016, the Presidential Medical Centre announced an auction for comprehensive building maintenance at public expense. Chisty Svet Plus offered its services for almost €300,000 and won the government contract. Their only competitor was Upravlyayuschaya Kompaniya Fasilikom, whose bid was only €388 higher. In other words, the two Apsits-controlled firms simulated bidding competition.

This is not the only manipulation of this kind. BIC found a total of nine bogus tenders involving Apsit companies that were won through this scheme. Chisty Svet Plus prevailed in each of them, which brought its owners at least €380,000 at the current exchange rate from the Belarusian public purse.

The case of Belarusian Railways

We discovered another scheme involving the Apsits’ business when we analysed the 2015 tender win for the maintenance of the Brest Railway Car Station of the Belarusian Railways. Chisty Svet Plus was the winner there, too. Twenty days after the contract was signed, the parties entered into an additional agreement, according to which, as the Brest media reported, the prices of some items increased a thousandfold.

As a result, according to local journalists, Brest Railway Station paid about 11 million roubles to Chisty Svet Plus, although the original contract value was barely 1.6 million roubles.

Aliaksandr Klachkou, then-foreman of the Brest Railway Car Station, was the first to draw attention to the inflated tariffs. The prosecutor's office investigated his complaint but refused to press charges. The head of the railway car station only received a warning "for committing an infraction enabling corruption". But then, the vigilant Klachkou was fired. The court reinstated him, but some time later he voluntarily resigned from Belarusian Railways.

The case of VTB Bank, Minsk Kristall Holding and the Presidential Medical Centre again

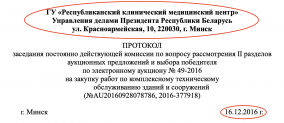

Another scandal involving Chisty Svet Plus broke out in 2019. Again, the case involved government contracts. At that time, the firm's director Valery Hatouchyk was detained for bribery in Belarus. With the help of CyberPartisans, we learned the details of three accounts in this case.

According to the case files, on two occasions Hatouchyk passed on a bribe to an employee of VTB Bank to ensure that Chisty Svet Plus would receive a contract. The amount of the bribes was at least $2,500. Hatouchyk gave $500 to Dzmitry Kisel, deputy general director of the Minsk Kristall spirits holding, to ensure timely payment for work done, and the same amount to Liudmila Liubchuk, chief engineer of the Presidential Medical Centre, "for her loyal attitude in accepting works".

We do not know the outcome of this criminal case. What we do know, however, is that even after the investigation, Chisty Svet Plus continued to win government tenders with a total value of over one million Belarusian roubles in contracts. Among others, the company signed another contract with the Presidential Medical Centre for 17 thousand Belarusian roubles five months after Liubchuk received the bribe from Hatouchyk.

However, the Apsits' ambitions were not limited by Belarus' borders. Neither were the court proceedings.

Kremlin cleaner becomes a rival to Putin’s chef

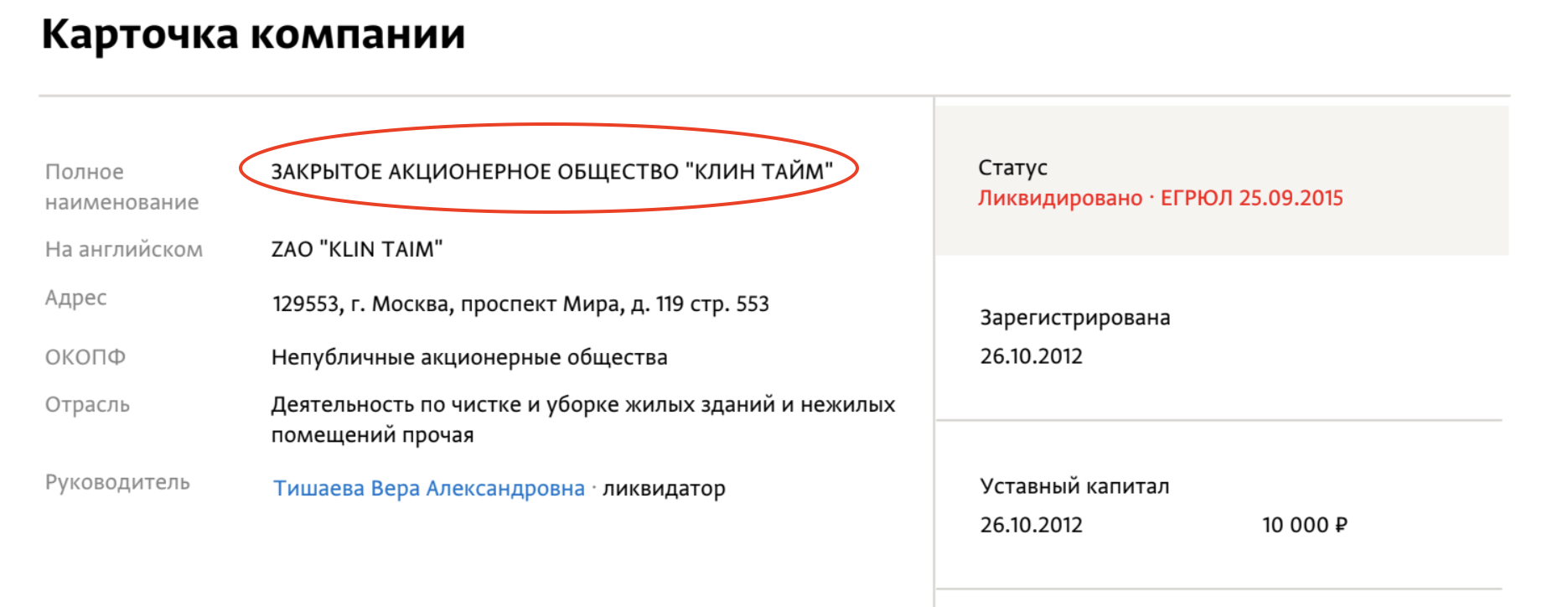

In late December 2013, Klin Taim was awarded a Russian government contract to clean the Kremlin Palace each year. It worked under the brands Chisty Svet and Chisty Svet. My Delaem Mir Chische, which is a clear link to Eduard and Elena Apsits.

The firm was given €280,000 from the public purse. In early January 2014, it organised the cleaning of the Kremlin Palace after the Christmas party for large families, kids with disabilities and orphans. We don’t know which Apsits’ employees were responsible for this charity event. However, we do know that some of them could not be legally employed by the companies.

Four months after the Kremlin Christmas party, the Moscow police detained staff members of a major cleaning firm. Industry media reported that it was the Apsits’ Fasilikom group of companies. They were accused of illegally employing migrants from Uzbekistan, who complained of low wages and slavelike working conditions. The outcome of the criminal case is not clear, as in the case of the Belarus trial. But the Apsits’ business in the Russian Federation did not close after that incident.

Our colleagues from Vazhnye Istorii have scrutinized hundreds of Russian state procurements involving companies under the brands of Chisty Svet and Chisty Svet. My Delaem Mir Chische and calculated the total amount of contracts. It amounts to more than 100 million euros at current exchange rates for the period from 2007 to 2019. Apart from the Kremlin Palace, the customers include Rostelecom, Sheremetyevo Airport, the Supreme Court and Russian Railways.

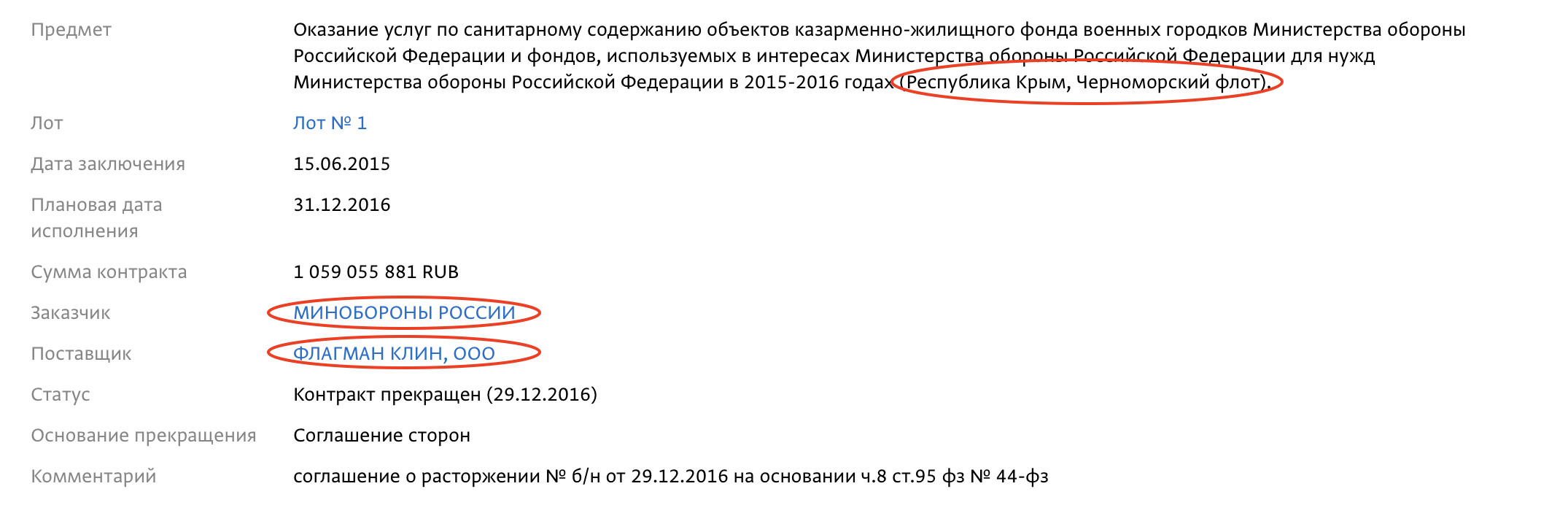

Companies associated with Apsits also worked for the Russian Ministry of Defence. For example, Flagman Klin won tenders to clean barracks in occupied Crimea. This firm used the trademarks Chisty Svet and Chisty Svet. My Delaem Mir Chische. According to the contracts concluded in 2015-2016, the company received about €30 million. Galina Sirotinina was the manager and owner of Flagman Klin in 2016. Before that, she worked at the company Chisty Svet Service, which was owned by Eduard and Elena Apsit.

The military cleaning market is estimated to be worth billions of Russian roubles and, as RBK Group found out, the Apsits share it with Yevgeny Prigozhin, the founder of the Wagner Group. Mindful of the Apsits’ companies machinations in Belarus, BIC checked how honestly they were competing with Prigozhin and examined the Russian Defence Ministry’s tender history.

Possible collusion with Yevgeny Prigozhin

In 2016, the Federal Antimonopoly Service of the Russian Federation (FAS) revealed cartel collusion in auctions for comprehensive maintenance of military camps and other facilities. The tenders were won by one of the eight companies involved in the anti-competitive agreement. They refused to engage in full competition and, as a result, all government contracts worth almost €245 million were awarded a negligible – less than 1.5% – reduction in the original maximum price. In the course of the investigation, the antimonopoly agency was able to prove a €28 million collusion.

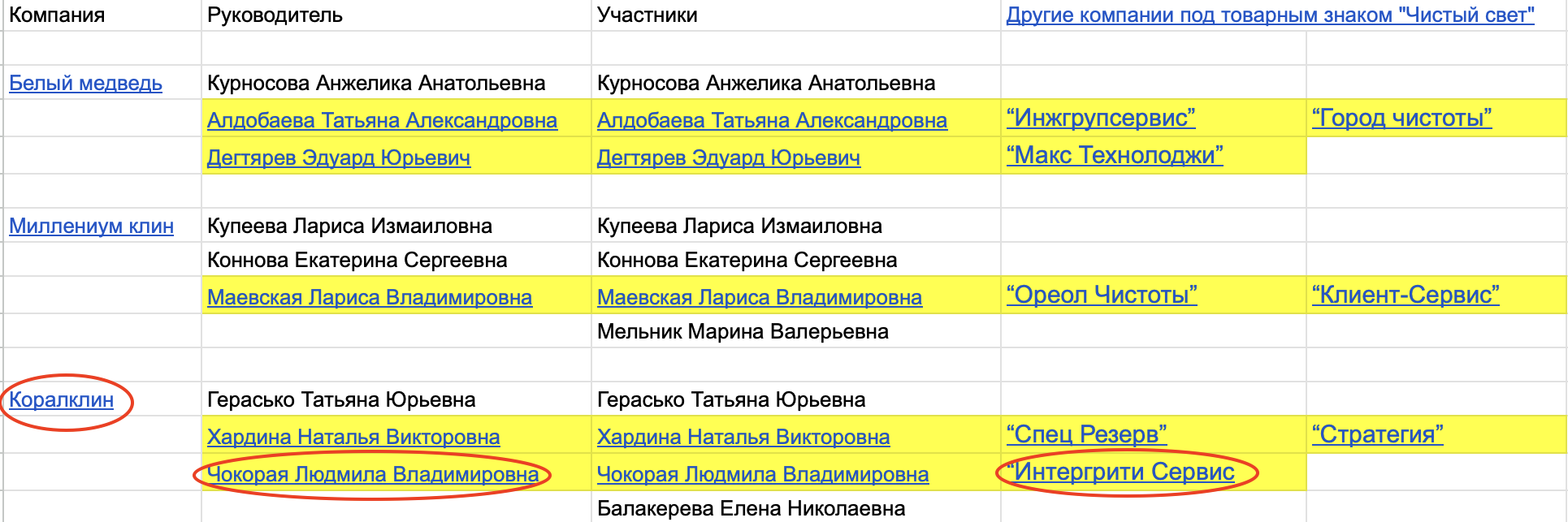

The FAS then divided the machinators into two groups. The first group included Komponent, Ekobalt, RusKompleks, Spetsresurs and Megaline. The Russian Anti-Corruption Foundation figured out that they were linked to Yevgeny Prigozhin. The second group consisted of Bely Medved, Koralklin and Millennium Klin. The individuals behind them were not known before our investigation.

In the FAS files, we saw that the three companies used the same IP address when submitting bids. Moreover, the bids were created under the same accounts and submitted by the same users. According to Russian FAS experts, this indicates "long-lasting and stable relations" between the companies.

BIC investigated the composition of the managers and owners of these companies. It turned out that many of them had previously worked for companies under the Chisty Svet and Chisty Svet. My Delaem Mir Chische brands. For example, Lyudmila Chokoraya was the director and owner of Koralklin. She also ran Integrity Service, which used the Chisty Svet and Chisty Svet. My Delaem Mir Chische trademarks.

We called the business lady. She confirmed that she worked for the Apsits’ group of companies, but claimed that she was responsible for performance quality, not the tenders.

BIC unsuccessfully tried to contact other former managers and owners of these companies. Many of the phone numbers are unavailable, and all three companies have been liquidated. As Lyudmila Chokoraya assured us, the Apsits’ Fasilikom group remains the leader in the Russian cleaning market. That cannot be said of their Ukrainian branches.

From cleaning to laundering

While the Chisty Svet and Chisty Svet. My Delaem Mir Chische trademarks branded companies were receiving orders from the Russian military, the Apsits were operating unhindered in the Ukrainian market. There, the Belarusian businessmen set up the Chisto group of companies back in 1997 and, as in Russia, were involved in a bid-rigging case.

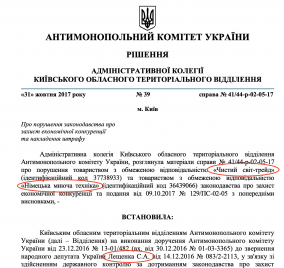

In 2016, the Lviv branch of the Ukrainian Railways announced a tender for the supply of washing equipment. Two companies made an offer: Nemetskaya Moyuschaya Tekhnika and Chisty Svet-Treid. The latter won and was awarded a contract for €4,500.

In 2016, the Antimonopoly Committee of Ukraine received a complaint about this tender from people's deputy Serhii Leshchenko.

He noticed that competition at the auction was imitated by the companies. The owners of the Nemetskaya Moyuschaya Tekhnika and Chisty Svet-Treid were the same people, the companies’ offices were located at the same address in Kyiv, and they applied for the tender from the same IP address. Eduard Apsit was among the owners of Nemetskaya Moyuschaya Tekhnika. The companies were found guilty of violating antimonopoly laws and were fined €1,000 each.

After the occupation of Crimea and the outbreak of war in Donbas, Eduard Apsit, who has a Russian passport, started withdrawing from Ukrainian companies associated with him. By November 2019, he had no business assets left in Ukraine. His long-time partners continued to run the companies. This fact caught the attention of Latvian investigators, who in 2019 launched an investigation into Apsit’s laundering of €73 million. They believe that de jure the Ukrainian business has been transferred to his trustees, but de facto he is still in charge.

“There are two criminal cases in court, in which the prosecution is represented by two public prosecutors from the Riga District Prosecutor’s Office. A total of 73 million euros has been blocked in these cases. The movement of these funds has been established, as have the beneficial owners,” Aiga Eiduka, spokeswoman for the Latvian Prosecutor’s Office, told TV3 Latvia.

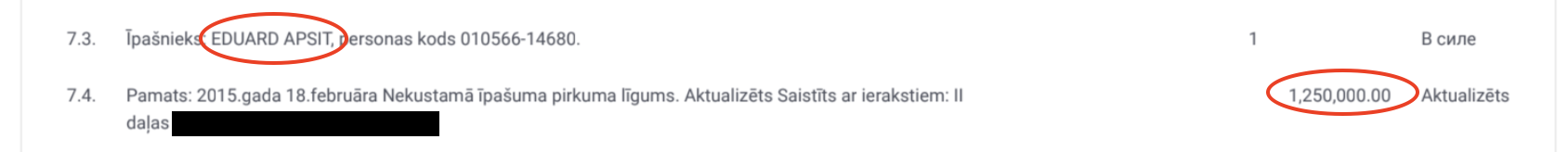

According to Latvian court documents, Apsit transferred the money he earned in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine to the EU. This allowed him to enjoy peace at a resort in Jurmala. There, 200 metres from the Baltic Sea, the family has a €1.2 million worth villa.

Eduard Apsit met with us and presented his position on this case. According to him, he has never been prosecuted either in Russia or in Belarus, and, as far as he knows, there are no criminal cases against him in Latvia and other countries. He claims that he does not know and did not have business relations with Yevgeny Prigozhin. Apsit denies that the firms he controls engaged in cartel arrangements and insists that neither he or companies under his control received money from the Kremlin or the Russian Ministry of Defense.

Latvian authorities continue to investigate this case.

Dear readers!

The following inaccuracies were discovered in this article.

In the case of the tender for the Brest locomotive depot maintenance (held in 2015), the amount of money discussed in the article was in non-denominated rubles. The audit report from the prosecutor's office (dated July 2016, after the denomination) did not indicate that the amount was not denominated. So this led us to the conclusion that we were dealing with denominated rubles. In the original investigation, we did not clarify this and applied the ruble exchange rate after the denomination. We offer our apologies.

Also, in the investigation, we did not mention that along with two companies related to Eduard Apsit, the third party, an affiliated company of the Presidential Administration, had participated in the tender of the Republican Clinical Medical Center of the Administration of the President of the Republic of Belarus.

Though, in our opinion, these mistakes do not change the essence of the investigation, we apologize over again.

The full story with BIC’s comments on possible errors in the material, can be found here.