Businesses have long been setting up shady schemes with rogue firms and affiliated companies to increase the minimum bid in state tenders. Indeed, international stats show average procurement cost overruns of 20 per cent when collusion occurs.

But the latest bill of amendment that might be passed by February 2023 aims to legislate affiliated entities out of state procurement.

The Minister for Antitrust Regulation, Alexei Bogdanov, says the new law will be saving the taxpayer around 1bn Belarusian rubels annually. Mr. Bahdanau says affiliated collusions are a major corruption factor leading to procurement cost increases.

The following case studies show how collusion works.

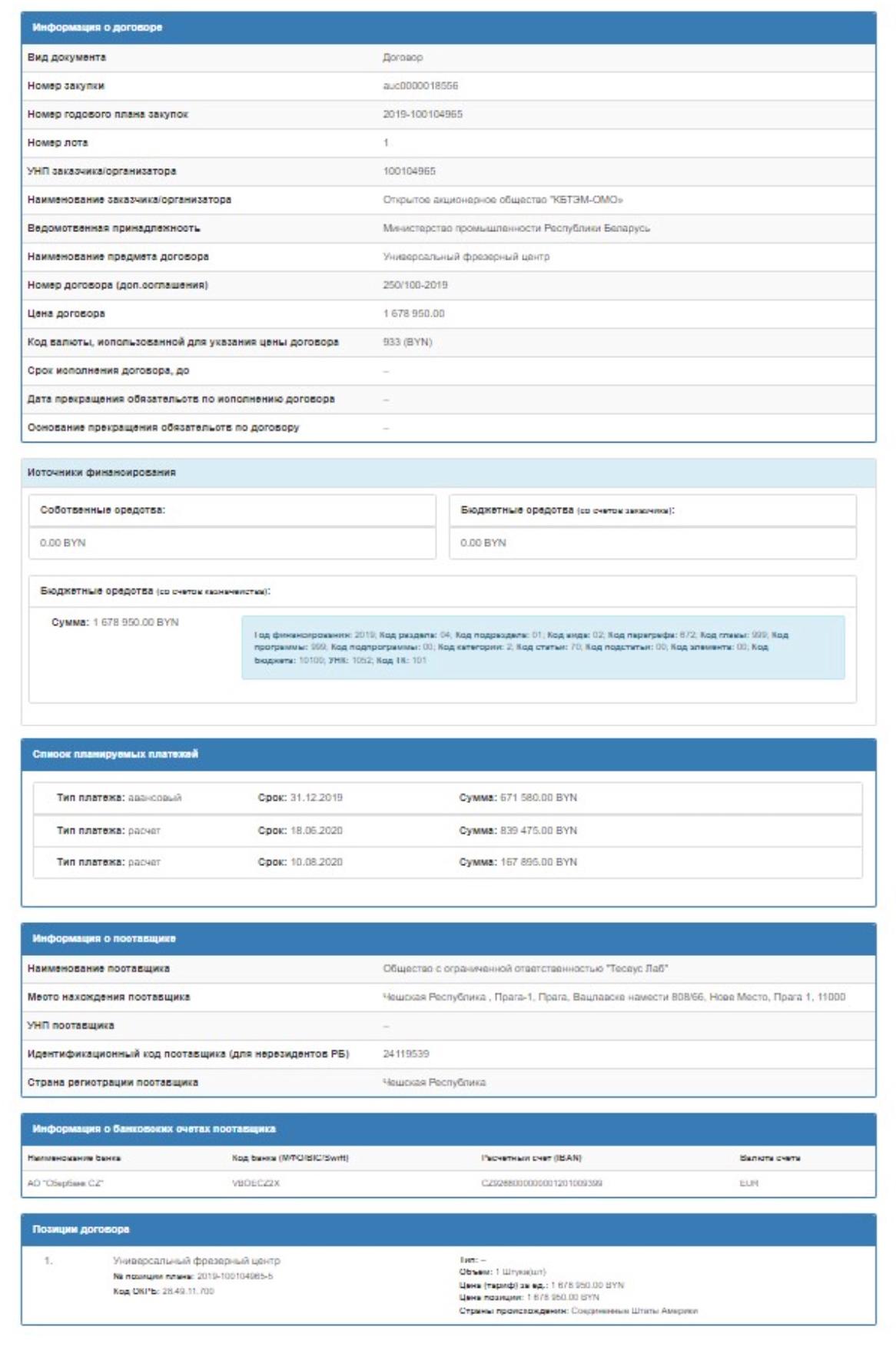

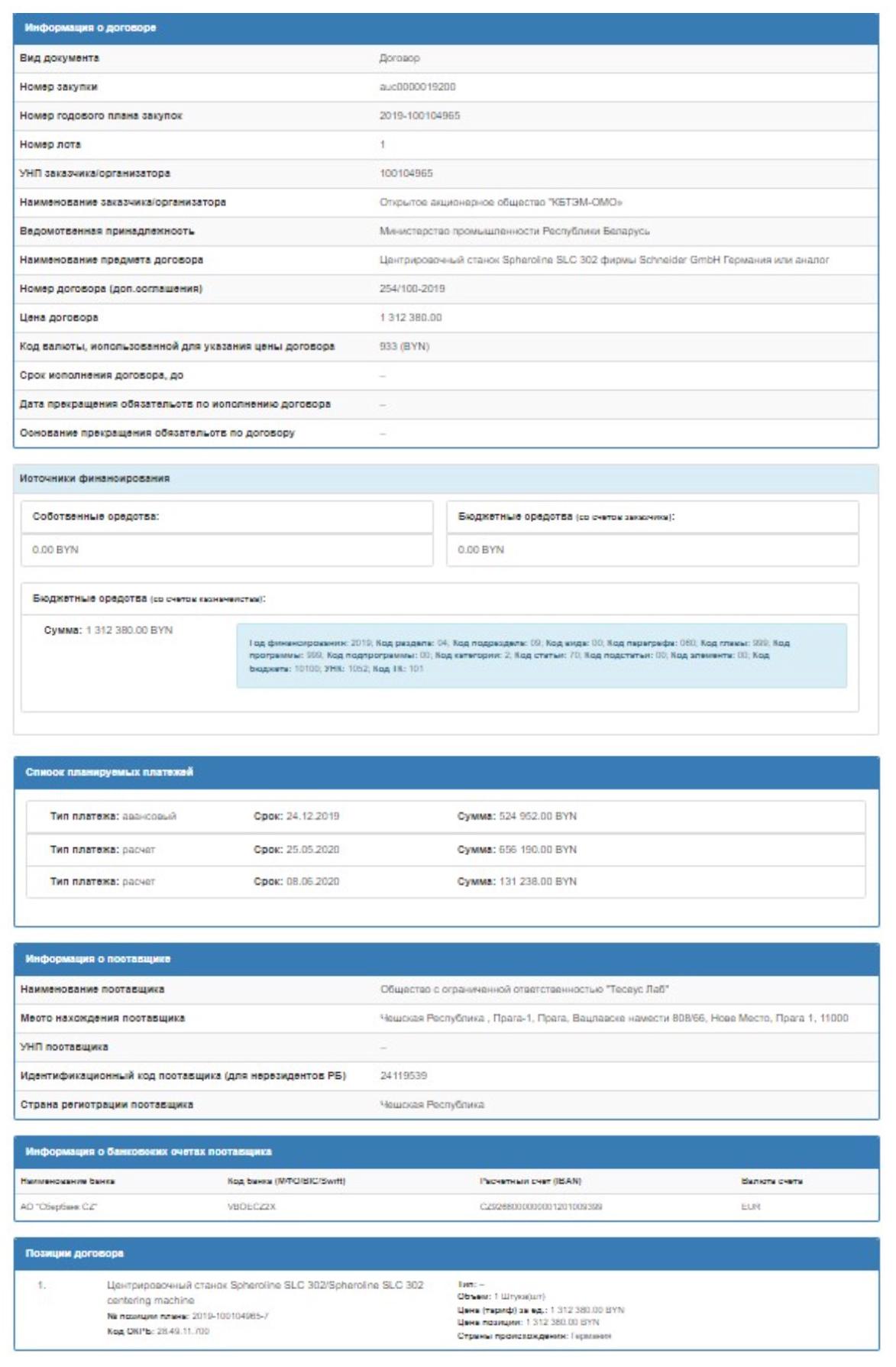

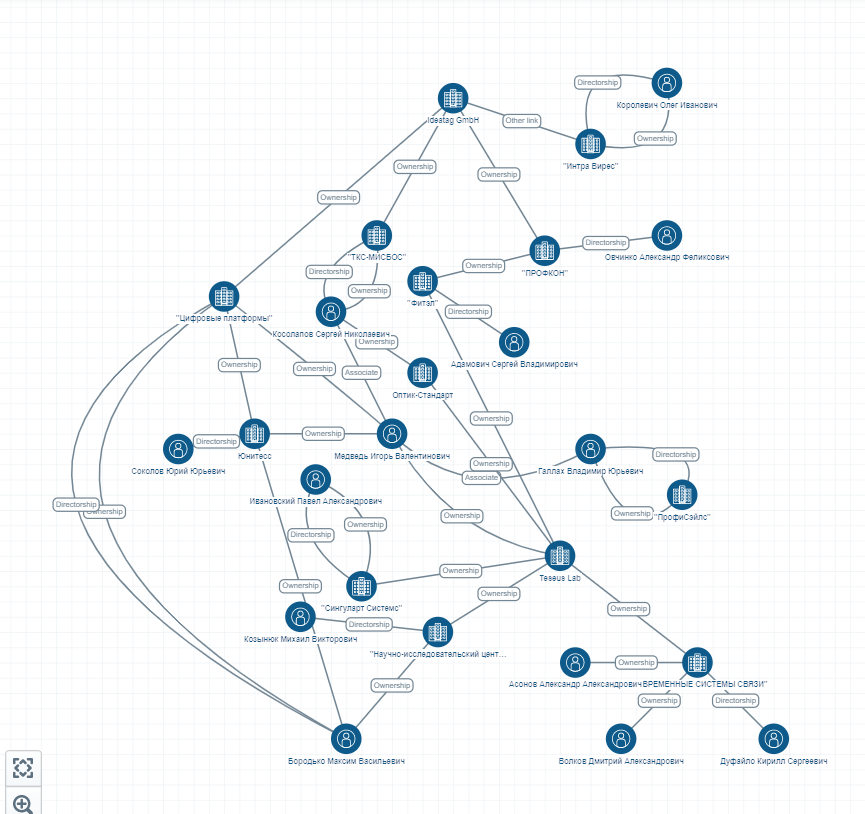

In 2019 a Planar holding subsidiary bought $2.5m worth of equipment via three tenders, each of them won by a Czech company Theseus Lab.

On the surface, the bidding looked as though the Czech firm had won three hard-fought battles with stiff competition. But a deeper analysis into the paperwork shows that the three companies were owned by one group of people.

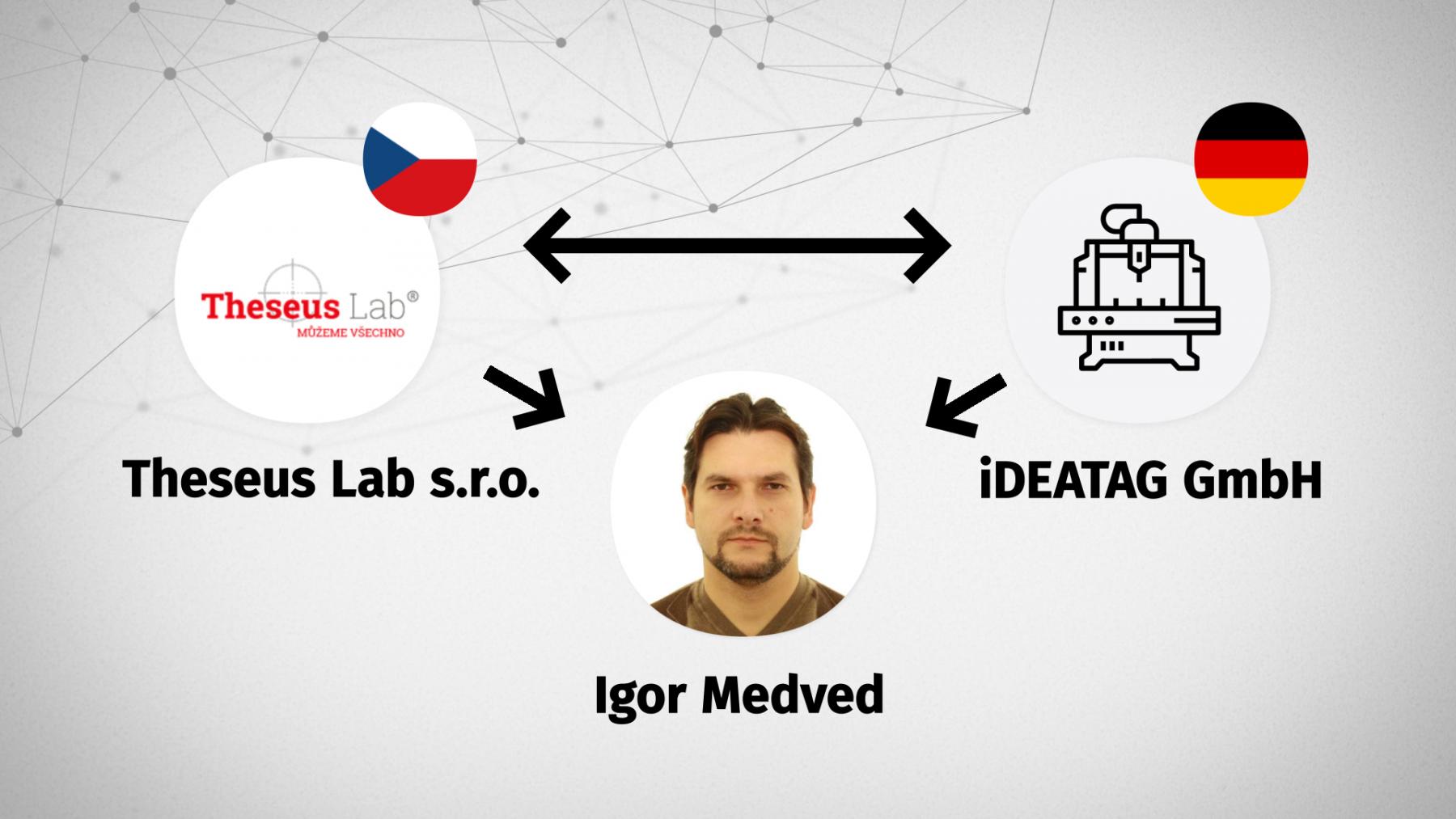

Another time, Theseus Lab wrestled Ideatag GmbH over a tender to supply an optical lens machining centre for making rifle scopes and other equipment. But a closer look shows the two companies were affiliated with the same person, businessman Igor Medved.

On a similar occasion, Theseus Lab faced a Russian-owned Yunitess over a tender to supply another machining centre. But again, it turned out Igor Medved had been the companies’ ultimate owner all along.

A look through procurement documentation for a centering machine shows Theseus Lab winning against a German-owned OptoTech and Yunitess after three tender attempts to secure the contract.

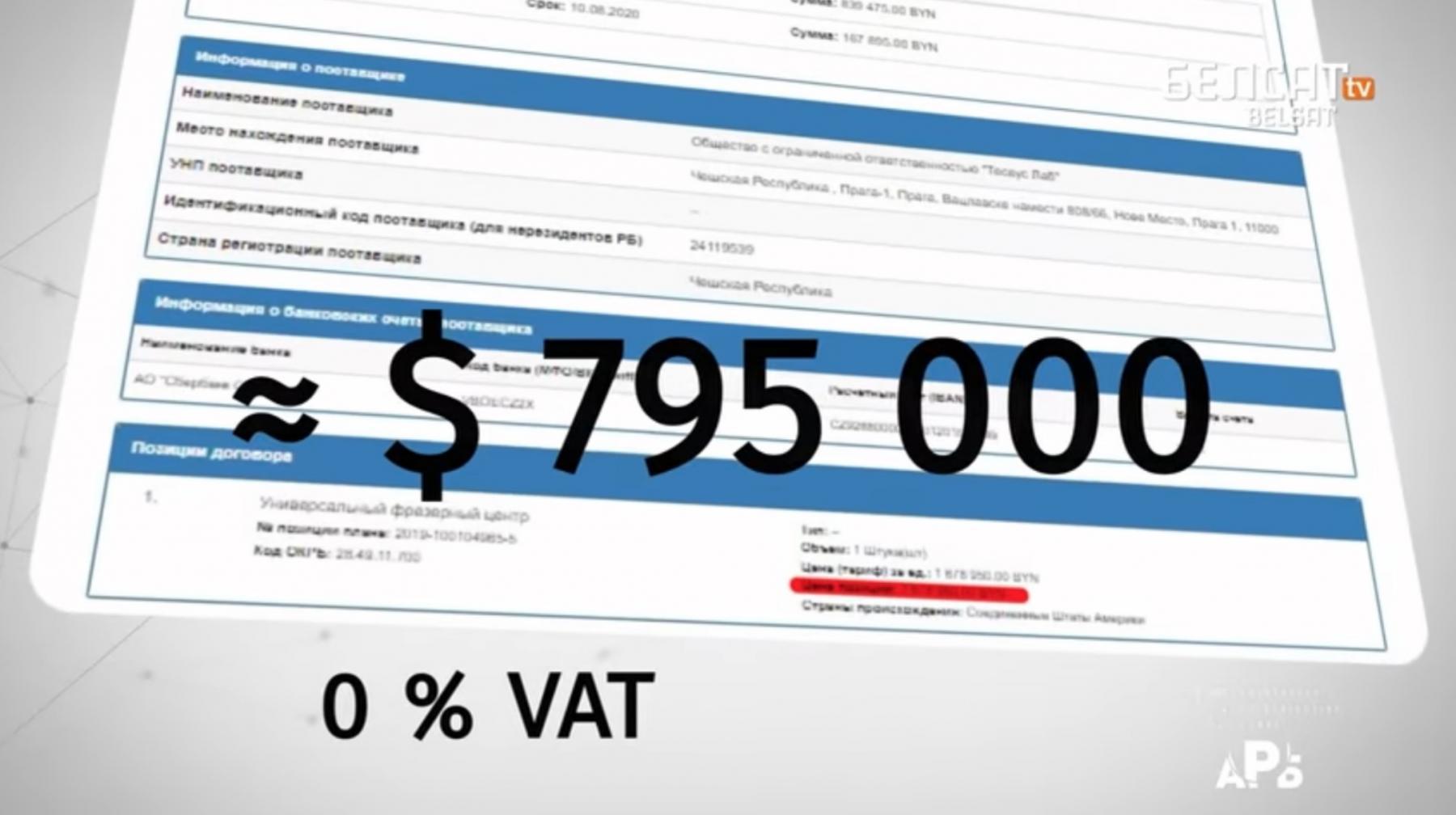

To appreciate the damage to the taxpayer, let us look at price differentials. Consider a machining centre that the state bought for $795,000 without VAT.

The same machine but with maximum specs is advertised for $489,000 on the manufacturer’s official website and includes a robotic arm.

Take out the robotic arm and the price goes down to $414,000.

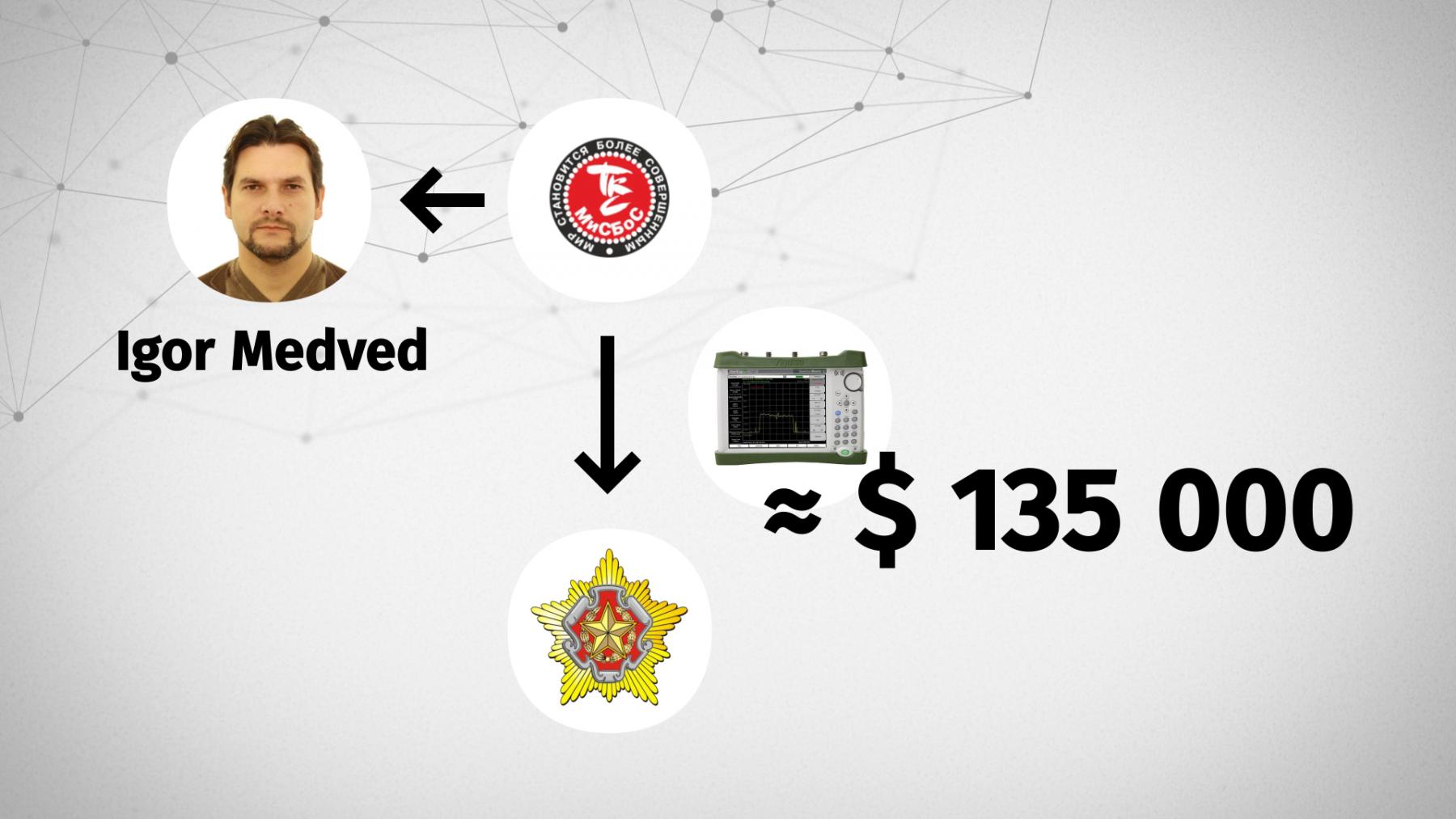

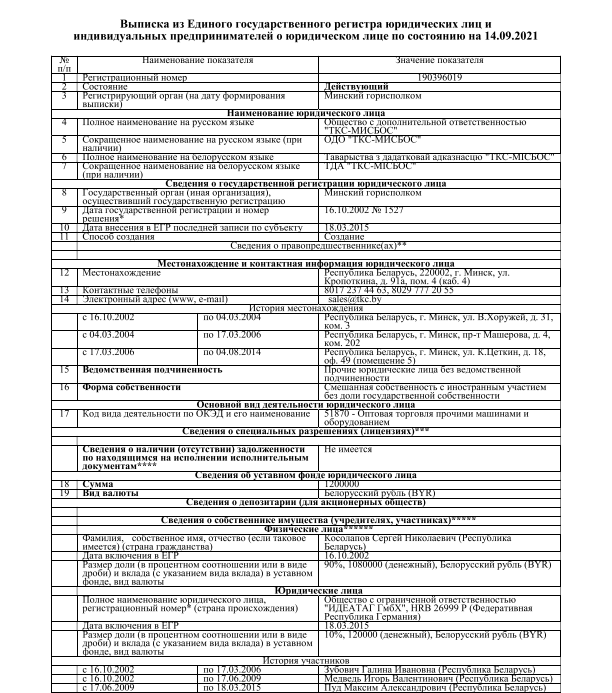

Mr. Miadzviedz’s companies have been active in procurement for security agencies and the arms industry. In 2014, a Miadzviedz-affiliated entity TKS-Misbos sold the Ministry of Defence a portable electric field spectrum analyser for $135,000 under a single-source procurement contract.

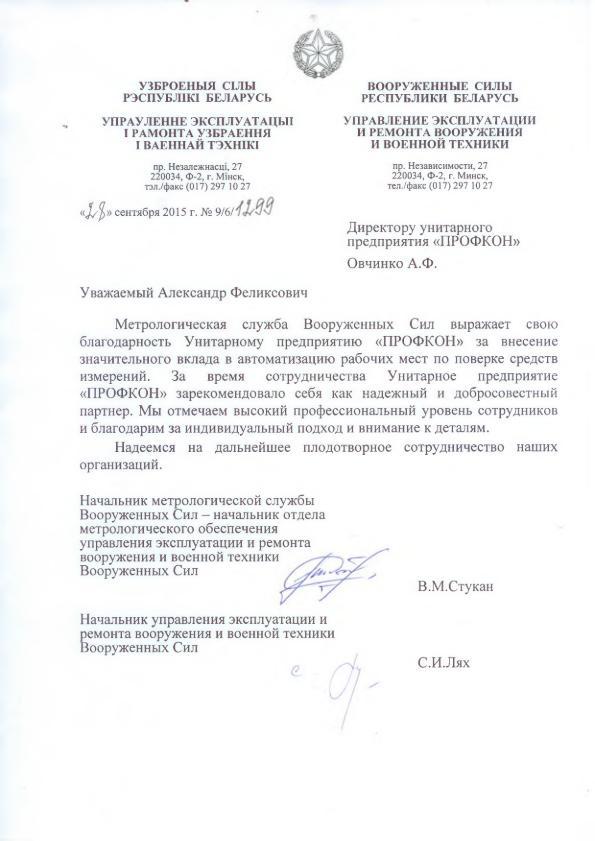

A year later Profcon, another Miadzviedz company, received a letter of acknowledgement from the Belarusian Armed Forces Metrology Unit for ‘significant contribution into automation of measuring equipment-calibrating workplaces’.

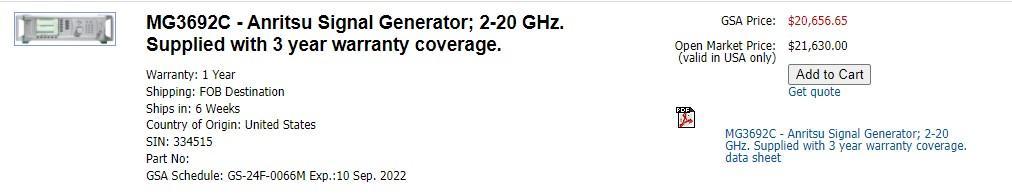

In 2019, TKS-Misbos won several tenders announced by KB Radar, a state-owned R&D facility that manufactures radars, radio suppression and drone capturing equipment. Ihar. Miadzviedz’s company sold the state manufacturer a signal generator for $45,000.

The same model costs $21,000 in the USA.

In 2020, TKS-Misbos sold a 2,000-dollar measuring microscope to NII Radyjomaterjalau, a radio equipment research institute that belongs to the state military-industrial complex, for $16,800.

In 2016-18, TKS-Misbos sold optical cabling to the State Border Control Committee. Another Miadzviedz company, Sovremyennye Sistyemy Sviazi, supplied optical and fibre optical cabling for the KGB and the Ministry of Internal Affairs via ‘requests for quote’ and ‘negotiations’.

In 2020, Theseus Lab supplied Integral, a state-owned chip manufacturer linked to the military-industrial complex, with a plasma generator for $207,000. In the tender, only companies affiliated with Mr. Miadzviedz and his associates had taken part, and they did not even try to imitate competition.

But the Miadzviedz network does not exclusively focus on the military-industrial complex. The businessman’s interests lie in industries such as telecommunications, banking, energy, and even equipment for educational institutions.

In 2021, for instance, Profcon won a National Educational Institute equipment tender for $870,000.

But Igor Medved himself is not a public person. His ex-colleagues also prefer to keep quiet about him.

Igor Medved graduated from the Faculty of Law at the Belarusian State University in 1996, and in 2002 he founded TKS-Misbos with his associate Sergei Kosolapov, an ex-military.

And according to our sources, Mr. Kasalapau enjoyed some serious connections with the military, among whom was his ex-business partner Dmitry Akimov.

We do not know what Igor Medved was doing between graduating and founding his first company.

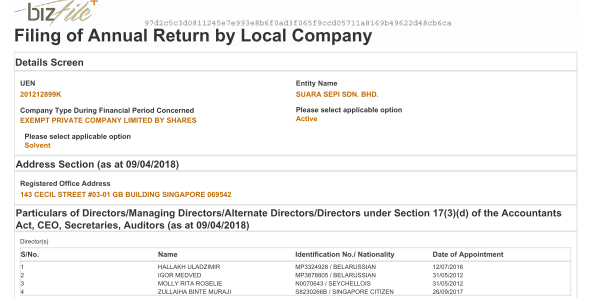

Between 2006 and 2014 he founded around ten companies in Singapore, China, Russia, Belarus, Czech Republic, and Germany.

For instance, Mr. Miadzviedz lists among the owners of a Singaporean company SUARA SEPI SDN.BHD.

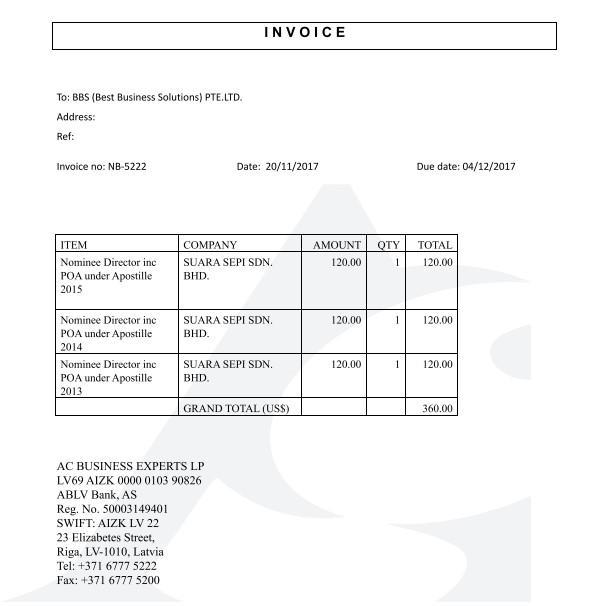

An offshore company provider serviced the firm, and its payments were going through a Latvian bank ABLV that has been accused of money laundering.

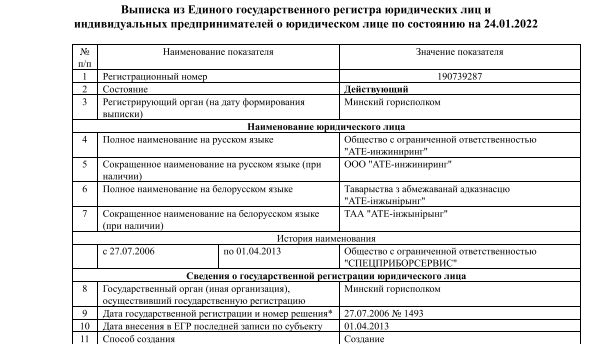

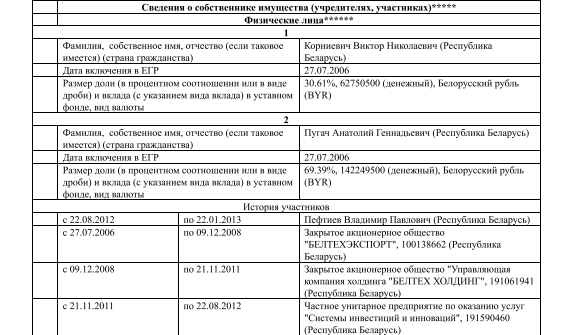

In 2012, Mr. Miadzviedz’s company group branded itself as A.T.E. Engineering. It even had a landing page. Around the same time, a company with a similar name, ATE Engineering, surfaced. In 2013, Spetspriborservis rebranded to ATE Engineering after being sanctioned by the EU for having a weapons kingpin Vladimir Peftiev as its co-owner.

But we could not find a documented connection between Mr. Miadzviedz and Mr. Pieftsieu’s businesses.

An ex-employee of Beltsekhexport (formerly Mr. Pieftsieu’s key asset) has confirmed that Beltsekh Holding changed entity names and owners several times while the sanctions were in place. “It was a very gentlemanly, but at the same time, an arms-length cooperation” – said the employee. “This helped the [the owners] steer their companies out of the sanctions’ way a few years later” – he added. Mr. Pieftsieu’s legacy remained, but “it no longer has such an influence within the system”.

Igor Medved has not responded to calls from Let’s Deal With It journalists.