For security reasons, this investigation does not identify specific organizations, names of sources, or details that might expose them.

The article was prepared in collaboration with the Alliance of Investigators and the Polish publication Rzeczpospolita, with the support of CyberPartisans.

The volunteer background

Minsk, August 11, 2020 – This is the third day of protests against falsifying of presidential election results. Demonstrators clash with police in the streets. The Interior Ministry reported that by night over 1,000 individuals had been detained. At this time, an administrative violation report was drawn up against 31-year-old Dzmitry Pratasevich. A brief charge description in his case from the MIA database, which was made available to us by CyberPartisans, reads as follows:

“At 23:10, Pratasevich D.P. ... committed a violation of ... traffic rules. Specifically, he was driving (...) sounding the horn without intending to prevent an accident. (...) Additionally, he crossed into oncoming traffic and failed to comply with repeated demands from a police officer to stop his vehicle. This resulted in the officers pursuing him”. [*]

In August 2020, Pratasevich requested assistance from volunteers and showed them the violation report. Over time, he began volunteering himself, identifying and helping victims of political repression. He distributed protest symbols and took part in marches. He used the alias “Tuteishy” and the “Pahne Chabor” handle on Telegram.

This story might have seemed ordinary in the context of 2020 events had Pratasevich not been detained during a protest in Minsk on November 1, 2020.

The escape that never happened

He was arrested along with his acquaintance, businessman Dzianis Hotta. Hotta was subsequently sentenced to 25 days of administrative detention for attending an unauthorized mass gathering and disobeying police officers. Pratasevich managed to escape directly from the security forces van. This is the story he told fellow volunteers when he turned up at their office the day after his arrest. This is what the BIC has been told by people who were working with him at the time. [*]

We found this detail important. To find out how Pratasevich allegedly managed to escape, we analyzed hundreds of photographs and reviewed available media files from that day.

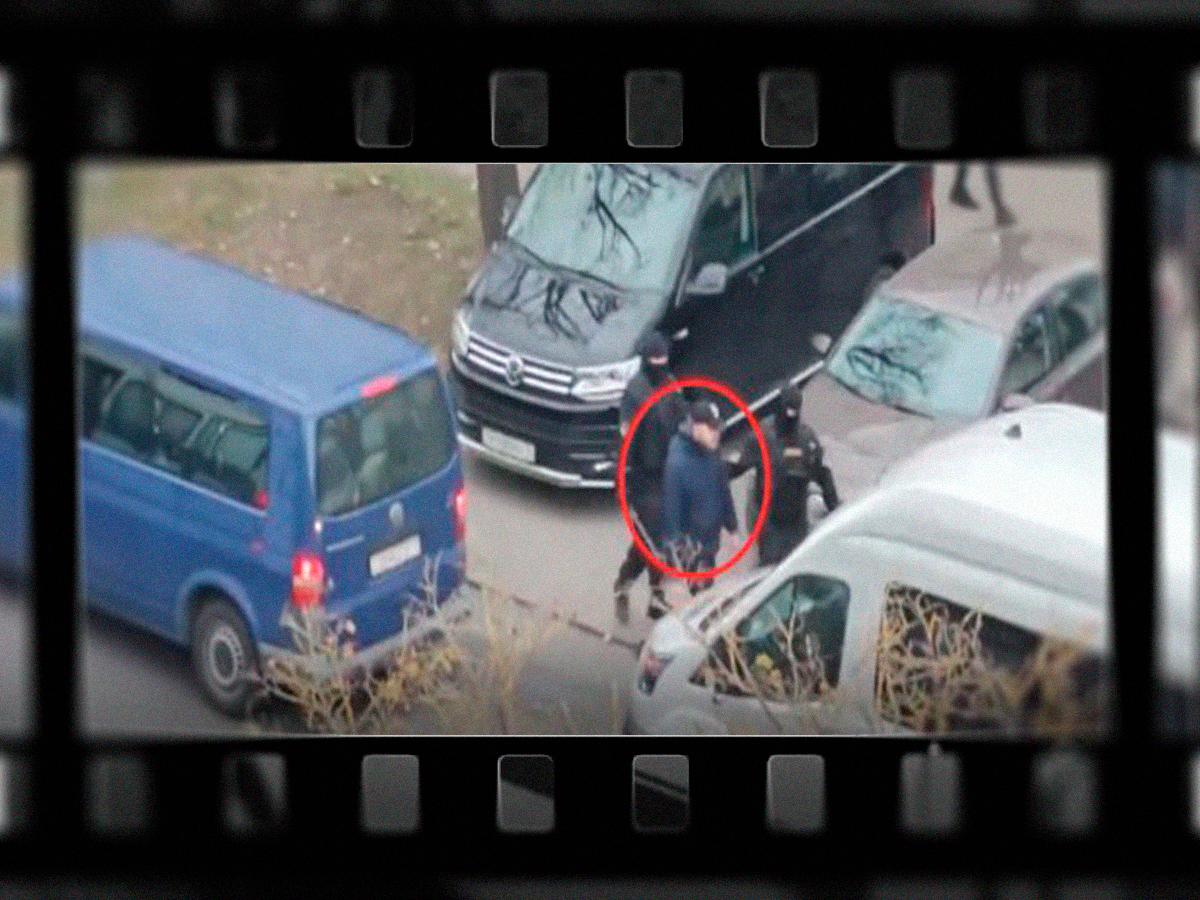

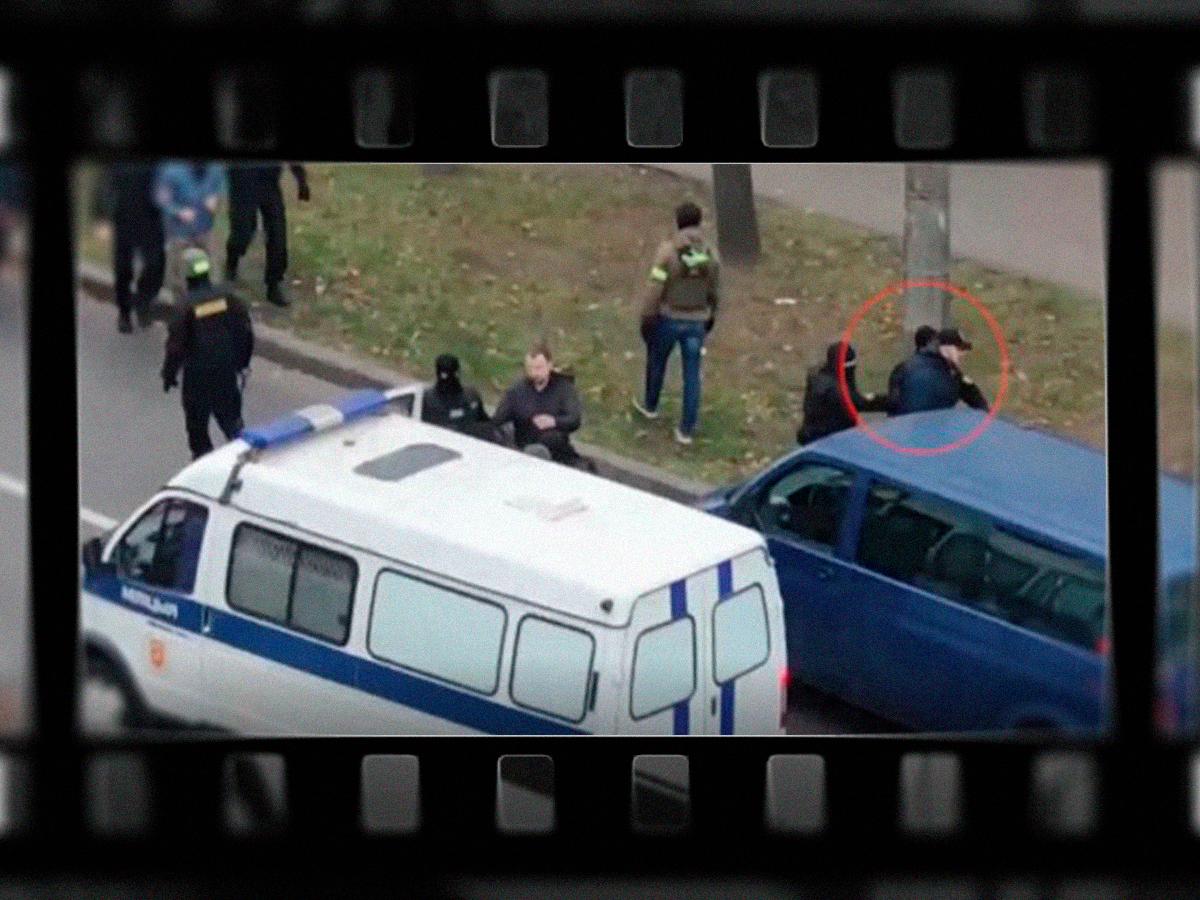

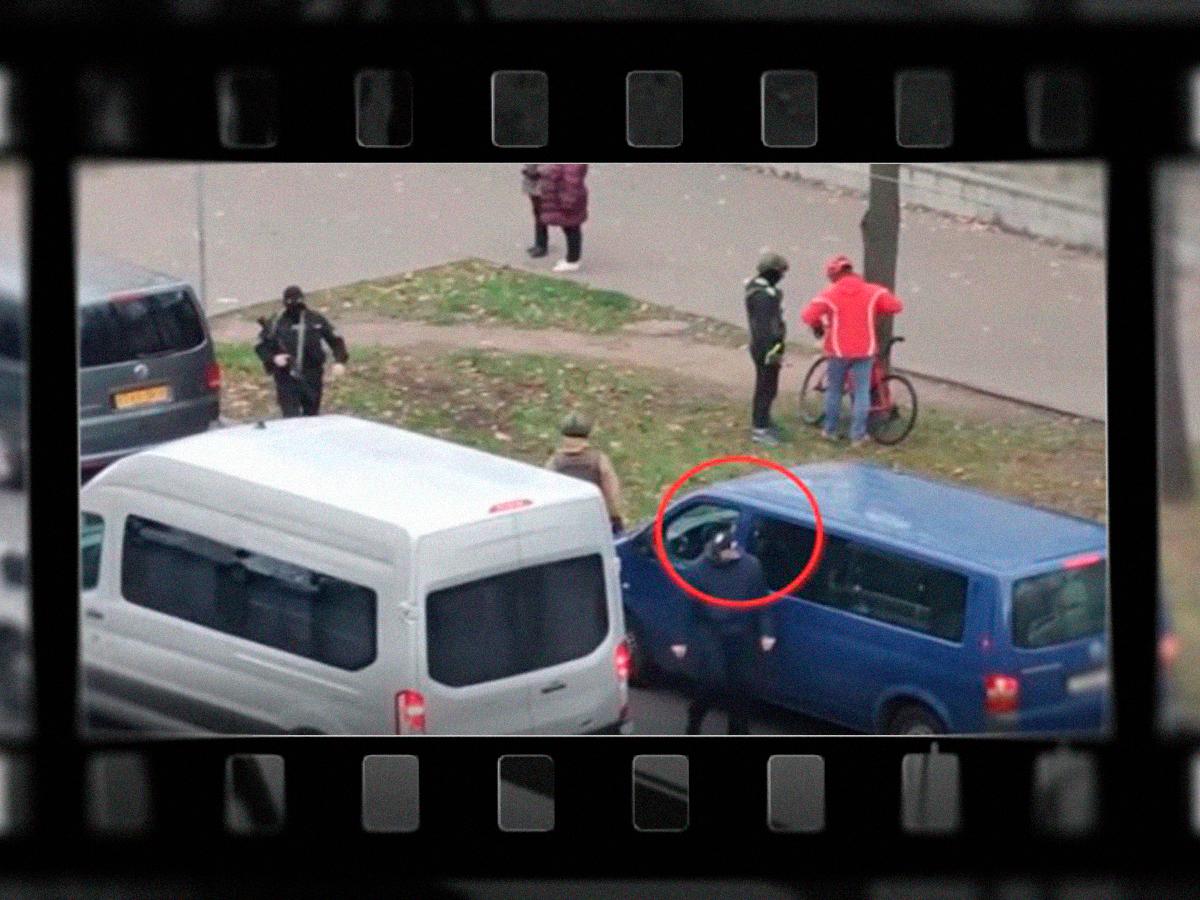

Pratasevich and Hotta were detained on Valhahradskaya Street. Two security force officers can be seen taking Pratasevich into a silver van in a video published by the TUT.BY news outlet on the same day. Pratasevich disappears for half a minute as the camera moves away. Then he reappears: first next to the police, then next to the vans, but without security forces. He is not running and no one is chasing him. Pratasevich turns, pulls up his hood, and walks away.

Apparently, he was released, and there was no escape. But as a matter of fact, Dzmitry Pratasevich did not exist.

Strangers in disguise

Dzmitry Pratasevich is a fictitious person. He became a member of a volunteer group with a specific mission to infiltrate. He worked with Maksim Kandratovich, a partner agent.

We spoke to two people who volunteered with them, helping victims of the protests. One of them told us that Dzmitry Pratasevich was interested in what the organization was doing and wanted to know the details:

“Who are our partners, especially abroad, with whom do we cooperate and communicate?... I’ve always been so disturbed that he asks many questions, and Maksim follows up with more questions, as if I were at an interview at the police. (Maksim Kandratovich) didn’t come so often. Sometimes they would come together, and usually you had the feeling that Dzmitry was somehow older, and Maksim was his assistant.”

Our source said that when Kandratovich first reached out to the volunteers, he also showed a certificate from a detention center. He said that “Maksim was generally a closed book” and would not discuss himself or his work.

Our second interviewee, who was involved in charitable projects, confirmed that the so-called Dzmitry Pratasevich was more open and proactive. Soon, he was leading a youth volunteer branch.

“Our idea was to invite young people from universities or high schools to form volunteer teams to expand the support. He agreed to run it,” interlocutor said.

According to volunteer, Pratasevich contacted victims of political repression using his own channels, filled in forms with their details, and produced records of arrests and dismissals of people for protesting.

BIC journalists examined one of the forms filled in by Pratasevich for assistance to victims. It lists 10 people. With the help of CyberPartisans, we found that at least five do not exist under the names given. Pratasevich received aid – vouchers for 200 Belarusian roubles (approximately $USD78 at the average exchange rate for 2020) to be spent on food – ostensibly for victims, but he provided lists and documents with false personal data. [*] [*]

We have yet to learn who received the aid.

Pratasevich also joinied the organizing committee to form the opposition political party Razam in spring 2021. This party registration was planned by supporters of presidential candidate Viktar Babaryka. Сampaign Ivan Krautsou, coordinator of the Razam organising committee, confirmed Pratasevich’s participation. Krautsou said only general information was known about this person, who “like all the other 5,000 people, gave his name to register as a member of the organizing committee to establish the Razam party.”

“He also attended one of our 2021 supporters meetings in Warsaw and one of our 2022 online education projects. Dzmitry Pratasevich had no access to our organization’s internal information and did not do any work on our behalf. We do not know his current whereabouts,” Krautsou said. [*]

Split, Belarusian-style

Pratasevich and Kandratovich’s detailed questions about organizations’ activities began to arouse suspicion among their colleagues. In early 2024, these colleagues turned to independent journalists, including BIC investigators. It became clear that Pratasevich and Kandratovich were not who they claimed to be.

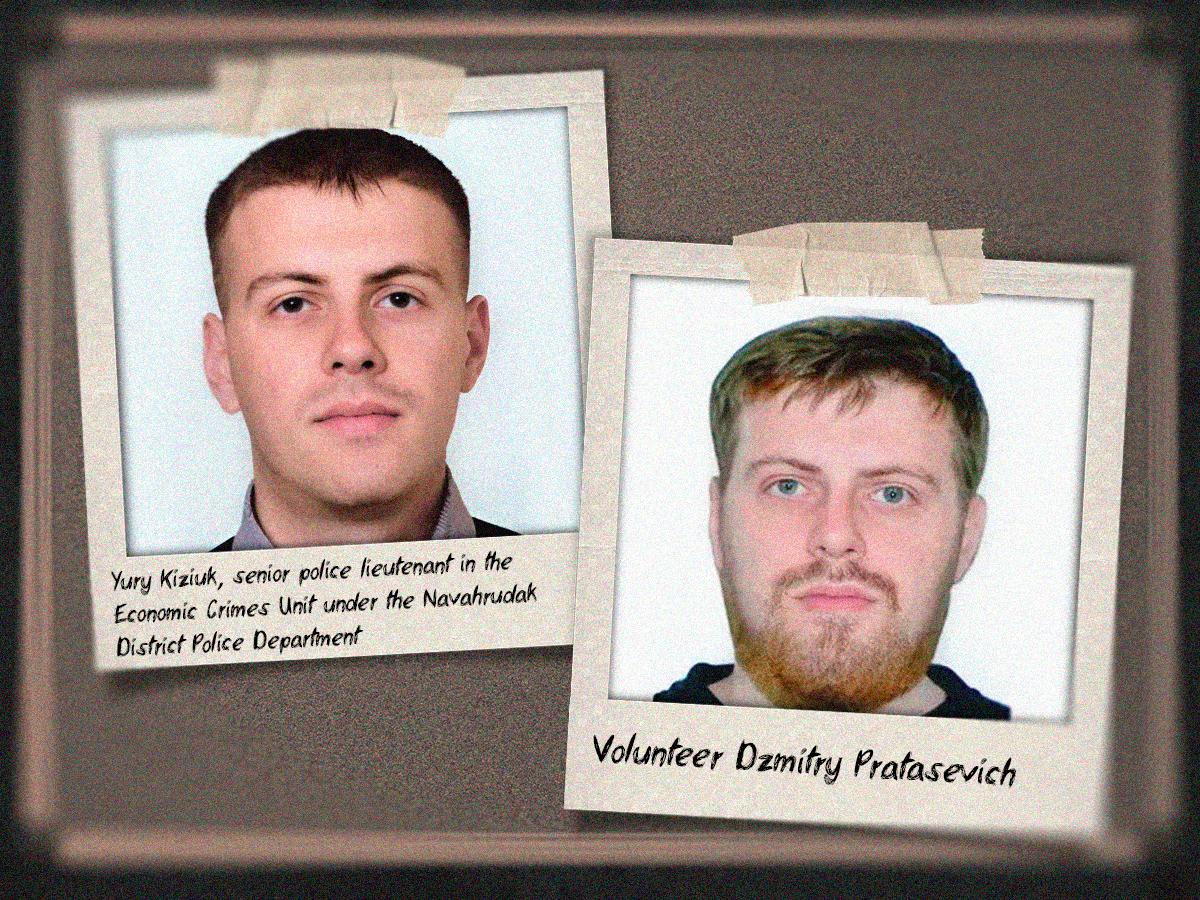

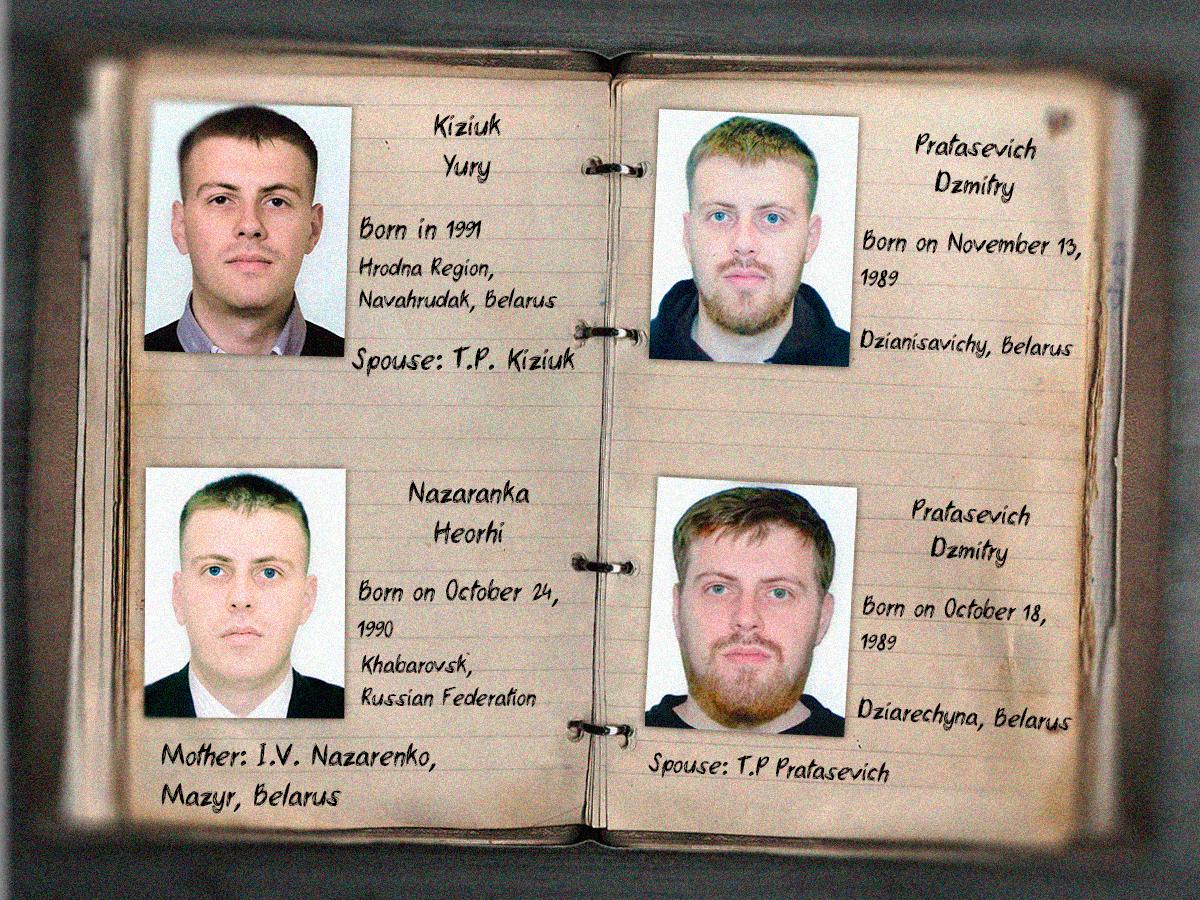

The photo on the left shows Yury Kiziuk, a senior police lieutenant in the Economic Crimes Unit under the Navahrudak District Police Department. The photo in the right show volunteer Dzmitry Pratasevich.

Yury Kiziuk became Dzmitry Pratasevich gradually. Our understanding is that the first step was the officer’s request to the State Security Committee in June 2015 about any vacancies. The BIC obtained it thanks to the CyberPartisans.

“Are there any vacancies in the KGB (recruitment procedure) for a current Interior Ministry employee? At the moment, I hold the position of operative of the Economic Crime Fighting Group under the Navahrudak District Police Department. I have been employed for one year and graduated from MIA Academy,” Kiziuk wrote.

We do not know what response he received. In 2016, his personal file contained a note that he had been “assigned for service at the Minsk City Internal Affairs Department”. Kiziuk resigned from the Ministry of the Interior three years later and was transferred to the Ministry of Defense. By then, he had become a captain, and his new assignment was in military unit 45523 in Minsk, under the Foreign Information and Communication Department of the Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU). [*]

The Association of Former Law Enforcement Officials of Belarus (BelPol) explained in an investigation that the aforementioned military unit had another designation — 64170.

It houses the Foreign Military Information Center, where intelligence information is collected, processed, depersonalized, and systematized, a former GRU officer told BIC.

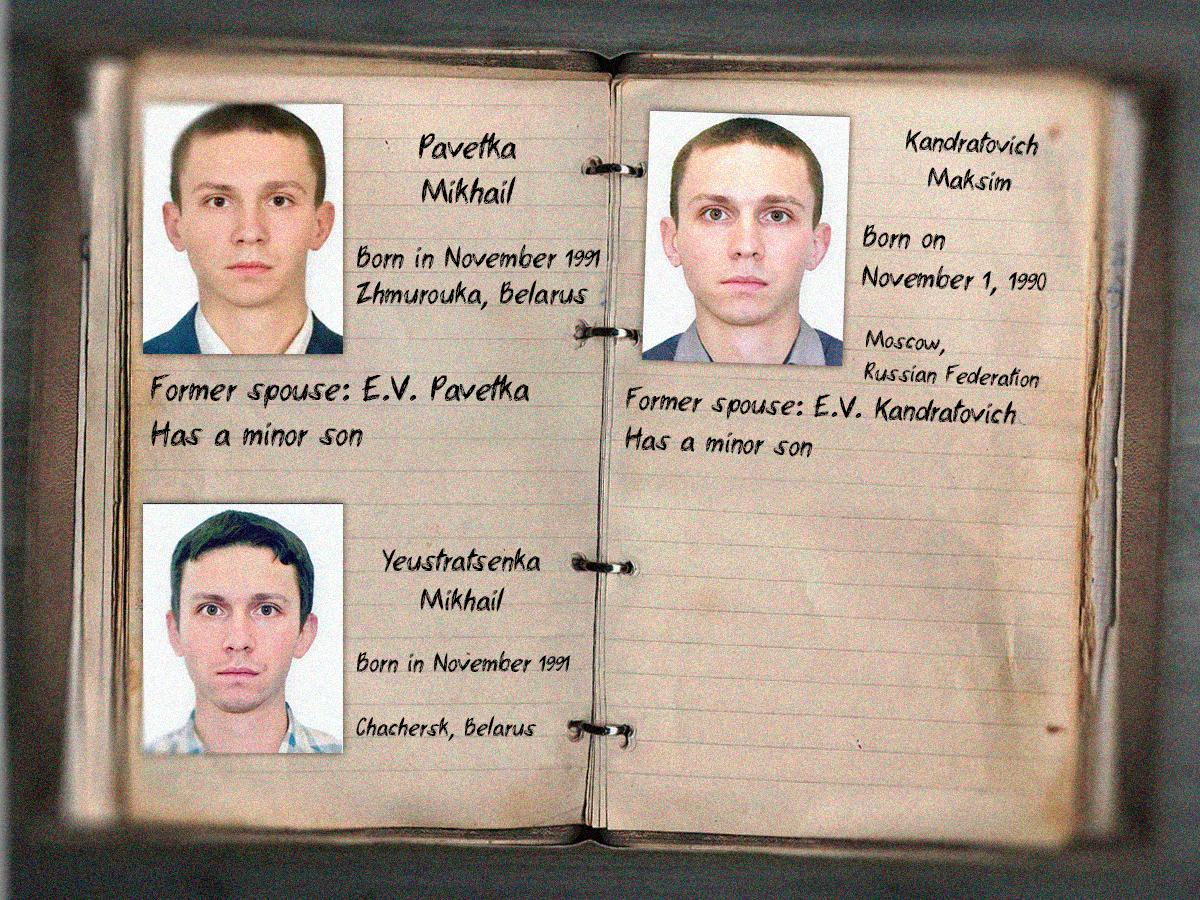

CyberPartisans data shows that a Mikhail Pavetka has served in the 45523 squad since 2018. This is the actual name of our second subject, Maksim Kandratovich.

In the November 30, 2016 edition of Belorusskaya Voennaya Gazeta, we found a photo of Pavetka in epaulettes. According to the caption, he had attained the rank of senior lieutenant of justice and was an interrogator in the Investigation and Search Department of the Military Command of the Armed Forces. [*]

Mikhail Pavetka is the same age as Yury Kiziuk. They studied at the MIA Academy at the same time, but Pavetka never worked as a police officer. From 2015 to 2018, he worked at the Military Commandant’s Office in Minsk before entering the intelligence service.

X in one

When post-election protests broke out in Belarus in 2020, Pavetka and Kiziuk were both still serving in military unit 45523, according to CyberPartisans. Each had several passports in different names. Both had alternate wives, children, and parents listed.

Yury Kiziuk held four passports at that time. According to information in his real passport, he was born in 1991 and has a wife, Kiziuk T.P. [*]

Another passport contains Kiziuk’s photo, but was issued to Heorhi Nazaranka, born in Khabarovsk in 1990. This person is a fake. E.V. Nazaranka from Mazyr is listed as his mother. There is a woman in the passport database who goes by that name. We tried to contact her about her supposed 34-year-old son, but she was unavailable. [*]

Kiziuk’s third and fourth identities have the same first name, surname and patronymic, Dzmitry Pratasevich, but other details vary. One Pratasevich was born on November 13, 1989. There is no information about his marital status, and his parents are fictitious. The other Pratasevich was born on October 18, 1989. He has a wife, T.P. Pratasevich, with the exact birthdate and photo as Kiziuk’s real wife. But her birth year is different. [*]

Three passports were issued with Mikhail Pavetka’s photo. The authentic one, with his first name and surname, says he was born in 1991 in the village of Zhmurouka in Rechytsa district. His ex-wife’s name is E.V. Pavetka. They have a minor son.

Pavetka’s second identity is Mikhail Yeustratsenka. The date of birth provided is different, but the month and year are the same as Pavetka’s. Yeustratsenka’s place of birth is Homel Region. The passport does not contain information about his wife or children.

The third identity is the volunteer Maksim Kandratovich. The CyberPartisans database indicates he is a native of Moscow, but a search of Russian databases did not yield any results. He has a former spouse, E.V. Kandratovich (Haponenka). Kandratovich’s son’s last name and patronymic were altered; his first name and date of birth match those of Mikhail Pavetka’s biological son. [*]

Going abroad

As reported by individuals who have interacted with volunteers Pratasevich and Kandratovich (in reality, Kiziuk and Pavetka), the two rapidly established connections with people who trusted them. Their activities under false names extended beyond Belarus.

In 2021, many Belarusian charitable organizations began to move to Europe. Kiziuk and Pavetka joined the exodus, spying on volunteers and pro-democracy activists in Poland.

According to the Polish register of legal entities, in December 2022 Mikhail Pavetka became one of the founders of the Polish company Arkmaxx Group under the name of Maksim Kandratovich. In August 2023, Yury Kiziuk also joined the company’s founders. He used a false passport in the name of Dzmitry Pratasevich. [*]

Reports are that the company has no business operations and was likely set up to make new contacts and reinforce agent backgrounds.

We spoke to Aliaksandr Karpovich, who is also listed as a founder of the Arkmaxx Group in the Polish register of legal entities. He said he met Pratasevich and Kandratovich in February 2022 and that they had been “recommended to me by people I trusted”.

“They said they are cronies. People vouched for them and said they had been verified. ... They wanted to register a company in Poland and open an office. ... I just gave them some recommendations and told them how to do it easier and better ... The war in Ukraine started, and we did not communicate for a while -- until around August 2022, I guess. I have no idea what they were doing before that time. But then they got in touch and asked for help registering the company”.

Karpovich told us they wanted the company to be a home sales office. The background story was that there was a production company in Belarus moving to Latvia, with an installation team, and their products were to be sold in Spain. A legal entity in Poland was needed to enter the Polish market.

Karpovich says he had no intention of doing business with them. He became a co-founder so he could complete the company registration, accounts and paperwork quicker. In return – “as a gift for great service” – Karpovich received a 25 percent stake.

According to Karpovich, Pratasevich joined the founders only in 2023. Two days before he was to submit all the documents, Pratasevich said he lost his passport and went to Belarus to change it.

Karpovich confirmed that the firm conducted no activity. Karpovich last contacted Kandratovich in early spring 2024. Kandratovich said he was busy, so they texted.

“I asked him when we could chat because it’s been so long since there’s been any contact. Take my share back, I don’t want to be involved. That was the end of it. ... I can’t contact him through Signal or any other messengers anymore. I’ve also tried emailing them, but I haven’t had a reply.”

The journalists of the BRC tried to reach both intelligence officers. However, the numbers that presumably belonged to them are either unavailable, have been assigned to other owners, or they did not respond to our calls.

Espionage Accountability

We do not know what other organizations the spies may have infiltrated under false names, or what information they gathered and passed on to the Belarusian authorities over four years.

We spoke to lawyer Ales Mikhalevich and asked him to comment on the facts we gathered. He confirmed that ordinary citizens cannot have more than one valid passport unless they are a member of the intelligence services. The lawyer also said that acting in the name of a fictitious person in the territory of another country is a criminal offense.

“Even if these documents had been obtained legally on the territory of the Republic of Belarus, such an identity has no existence. And in this case, there are clear signs of a criminal offense, and this person can, in my opinion, be held criminally liable for falsifying documents,” Mikhalevich explained.

He added that if there was evidence, they could also be prosecuted for espionage:

“Most EU penal codes contain articles on espionage, even if the actions are not directed against the country in question. This means that if a person has been an agent of a foreign intelligence service and has failed to report this to the local counter-intelligence service of the country in which they are located, that in itself is a crime. You can be imprisoned for five years if there is no harmful activity against the country. Suppose an individual is found to have engaged in activities that threaten the security of their country of residence. For instance, in the case of Poland, they may face a sentence of up to life imprisonment.”

The press service of the National Anti-Crisis Management, to which the BIC sent the request, said that it was aware of the Belarusian spies.

"We find it important to flag that this case is already being handled by the Polish authorities. It might be best to avoid publicity at this stage, as it could impact their work," stated the organisation’s representative.

The BIC journalists also contacted the Polish Prosecutor’s Office to inquire if the office knew anything about the activities of Pratasevich and Kandratovich in Poland. We have not yet received a response.

No panic

Franak Viachorka, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya's Chief Advisor, gave BIC some tips on how to avoid becoming a source of information for a spy. He said it's important to be mindful of information hygiene and to check the backgrounds of suspicious people.

“You can check that person’s background, see what social networks they're on, and ask for a recommendation from people who know them. There are organizations that can conduct inspections, such as BELPOL, for example. And remember, our strength lies precisely in solidarity, mutual support, and humanity. On one hand, let's be cautious, but let’s not lose our faith in people, because taking away that faith is the regime's goal”.

Viachorka also said that we should not overestimate the capabilities of special services, get paranoid, and accuse everyone of working with the KGB. He thinks that "this is exactly what the security services and the regime want — to make people distrust each other and split unity".

This materials/publication/video was produced with the financial support of the European Union. Its content represents the sole responsibility of the EU4IM Project, financed by the European Union. The content of the materials/publication/video belongs to the authors BIC and does not necessarily reflect the vision of the European Union.