Data on clients of Credit Suisse, a major Swiss bank, was obtained by the German edition of the Süddeutsche Zeitung and shared with the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) of which BIC is a member. The leak helped identify over 120 Belarusians who hold accounts with Credit Suisse.

As part of this investigation, the CyberPartisans helped us check high-risk Belarusian clients of Credit Suisse – those politically engaged or convicted of crimes. From the list, we selected three persons who could use the secrecy of the Swiss banking system for dubious purposes.

One of the subjects of this investigation is a former member of parliament whose reported income was several times lower than the amount of money in his Swiss account. The second one is a businessman who has been jailed twice in different countries. The third one is a businessman close to the Belarusian authorities dealing in petroleum products using unclear schemes.

All of them could use the secrecy of the Swiss banking system for dubious purposes. Sometimes banks do not make a thorough check of their clients. In an interview with OCCRP journalists, former and current Credit Suisse staff members explained this as a corporate culture that encourages taking risk for the sake of profit.

Honorary pension

It was the last summer day of 2008. An Audi was waiting in line to leave Belarus for Poland. Petr Kalugin, a House of Representatives deputy, was the driver.

He was finishing his third term with the status of a labor veteran and an honorary citizen of Salihorsk. Kalugin received these honors for his work at Belaruskali. Having started his career at the company as an ordinary locksmith, he rose to become the general director and held this position for almost ten years from 1992 to 2001.

The day after he crossed the border, Kalugin opened an account at the Swiss bank Credit Suisse for an unnamed company. At that time, he did not officially work for any company in Belarus apart from being a deputy of the House of Representatives. One year and seven months later, nearly $1.3 million was credited to his bank account.

With the help of the CyberPartisans, we found that Kalugin's income in the seven years from 2003 to 2009 totaled around $87,000. This is 15 times less than the amount in his Swiss bank account.

We contacted Kalugin for clarification, and he was unable to answer our questions on the phone. We started looking for answers ourselves, checking his biography.

Petr Kalugin is 81 years old. Born in Russia, he studied at the Leningrad Mining University and came to Belarus in 1966. He started working for Belaruskali and reached the top of the career ladder in 1992. Kalugin admitted that the production volumes under his management had fallen by more than 50 percent. But the quality of the products was appreciated abroad, and the company entered international markets.

Under Kalugin, Belaruskali was also slightly restructured. In 2000, the Trest Shahtospecstroy unit was separated from the company. Shahtospecstroy had been involved in mine construction since Soviet times, and Belaruskali's staff worked in those mines. Our source claims that one of the main owners of the privatised Shahtospeсstroy was its director Valery Startsev and that Kalugin actively supported this privatisation. The following year, Kalugin left Belaruskali to focus on his parliamentary career.

In the autumn of 2008, a few months after he opened an account with Credit Suisse, Kalugin's term in the House of Representatives ended. By 2009, he had already started working at Shahtospecstroy with his former contractor whom he had helped to become a private businessman.

Kalugin's appointment happened on the eve of a major project. In January 2010, Belarus agreed to build the Garlyk mining and processing facility in Turkmenistan worth about $1 billion. The project's general contractor, the state-owned Belgorkhimprom company, subcontracted the work to Shahtospecstroy. Two months later, $1.3 million appeared in Kalugin's Swiss bank account. As we have already established, he couldn't have earned it with his official salary.

The construction became a scandal. According to media reports, the Turkmen authorities accused Belarus of improper performance of the contract and filed a claim with the Arbitration Institute of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce, commonly known as the Stockholm Arbitration. The loss was estimated at $900 million. In Belarus, the claim was denied and a counterclaim of $400 million was filed. The arbitration has not yet been concluded. The potash plant in Turkmenistan did begin operation in 2017, two years after the launch was planned.

During that time Kalugin worked at Shahtospecstroy. He registered a small house in the Slutsk district; his wife registered a four-room apartment near Komsomol lake in Minsk and a two-story cottage near Salihorsk Reservoir.

Kalugin closed his Swiss bank account in August 2014.

Financial Crime in Russia

At Credit Suisse, we found two accounts belonging to Belarusian Albert Larytski. Both were opened in early 2011 – that's when the story unfolded that led to a Russian governor and Larytski being jailed. While a Russian company linked to him received state loans and went bankrupt, he deposited millions in his Swiss bank account. After being accused of financial fraud, Larytski apparently took part in a provocation against a liberal Russian politician. He has recently been released from prison and we were the first to hear his version of the events.

Larytski, 47, comes from Homel.

In the 1990s, he started his first business in his hometown, selling alcohol wholesale and retail. At that time, Larytski met businessman Juri Sudheimer. He was originally from Kazakhstan, but before the collapse of the Soviet Union, he moved to Germany and started a business producing filters and lubricants. He eventually opened a warehouse in Homel.

Sudheimer later moved from Germany to Switzerland, and Larytski went to Russia, where he became vice president of Zernostandart. In 2008, this agricultural holding company bought shares of the Novovyatskiy ski factory and soon began to modernise it. The plan was supported by the then-governor of the region, Nikita Belykh.

This project brought Sudheimer and Larytski together again. According to Sudheimer, at the request of Larytski, he provided some $40 million for the modernisation of the Novovyatskiy factory. But the project failed and the company fell into debt and insolvency. Hoping to return the money invested in the plant, Sudheimer turned to the FSB, and in 2015 Larytski was detained on suspicion of financial fraud.

According to the investigation, the Belarusian businessman (by this time he had received a residence permit in Switzerland) took loans from Russian Sberbank using fake contracts to buy equipment for plant modernisation, but transferred the money from company accounts to his personal account at the same bank, Credit Suisse.

Larytski commented to BIC as follows: «I live in Switzerland. Of course, I have a bank account. And, of course, I have transferred money from my company to this account. That is, I transferred money as an investment from my account to my company and then I got some of that money back. Not all, though».

We checked the history of Larytski's account opened in February 2011 during the modernisation of the Novovyatskiy factory. In May 2011 that account contained about $3 million. The maximum amount on the second account was about $275,000 in March 2014.

However, according to the investigation, Larytski withdrew a much larger amount – about $10 million – as a result of financial fraud. At his trial, he fully admitted his guilt, but he told us that he had been forced to do it:

«In the Lefortovo detention centre, everyone confesses – politicians, businessmen, ministers. According to the European Court of Human Rights, being in the Lefortovo detention centre is tantamount to torture. I was there for two years and four months. Trust me, if you got sent there, God forbid, you would confess to the Kennedy assassination».

Larytski believes his case was politically motivated and it was used to jail the then-governor of the Kirov region, Nikita Belykh, who was caught red-handed taking a bribe in Moscow in 2016. The prosecutor claimed at trial that Belykh received the money in exchange for patronage over the Novovyatskiy ski factory. Larytski allegedly gave Belykh €200,000 through intermediaries in 2011-2012, and Sudheimer allegedly gave him €400,000 in 2014-2016.

Before he was appointed governor in 2009, Belykh was the leader of the liberal Union of Right Forces, a Russian opposition bloc co-founded by Boris Nemtsov. After becoming governor, Belykh left all opposition organisations but did not abandon his liberal views – he appointed Alexei Navalny as his adviser.

The international organisation Transparency International suggests that the security forces might have used Larytski and Sudheimer as a «torpedo» in the case. This is the name given to a person sent to bribe an official as part of an operation.

The court sentenced Larytski to three years in prison. Sudheimer was not charged. Belykh received eight years for taking a bribe from Sudheimer and is still serving his sentence. Belykh was acquitted in the Larytski case.

After his release, Larytski worked for a while in Belarus. According to Sudheimer, at his request Larytski was imprisoned again, this time in Switzerland, but has recently been released.

Smells like big money

In January 2012, Credit Suisse opened an account for an unnamed company owned by a Belarusian businessman. By July, the account held more than $36 million. At that same time, Lithuanian businessman Vitold Tomaševskij was working with Credit Suisse Trade Finance. He opened an account in Credit Suisse for a company called Savoil.

According to our source, Savoil was involved in a 2011-2012 solvent and diluent scheme.

At that time, Russian oil and oil products were exported to Belarus free of customs duties. They only had to be paid when Belarus exported oil products made from Russian oil. Some of those goods were also not subject to customs duties, including solvents and diluents. Under the guise of these products, Belarusian traders began actively reselling other Russian oil products and evading customs duties.

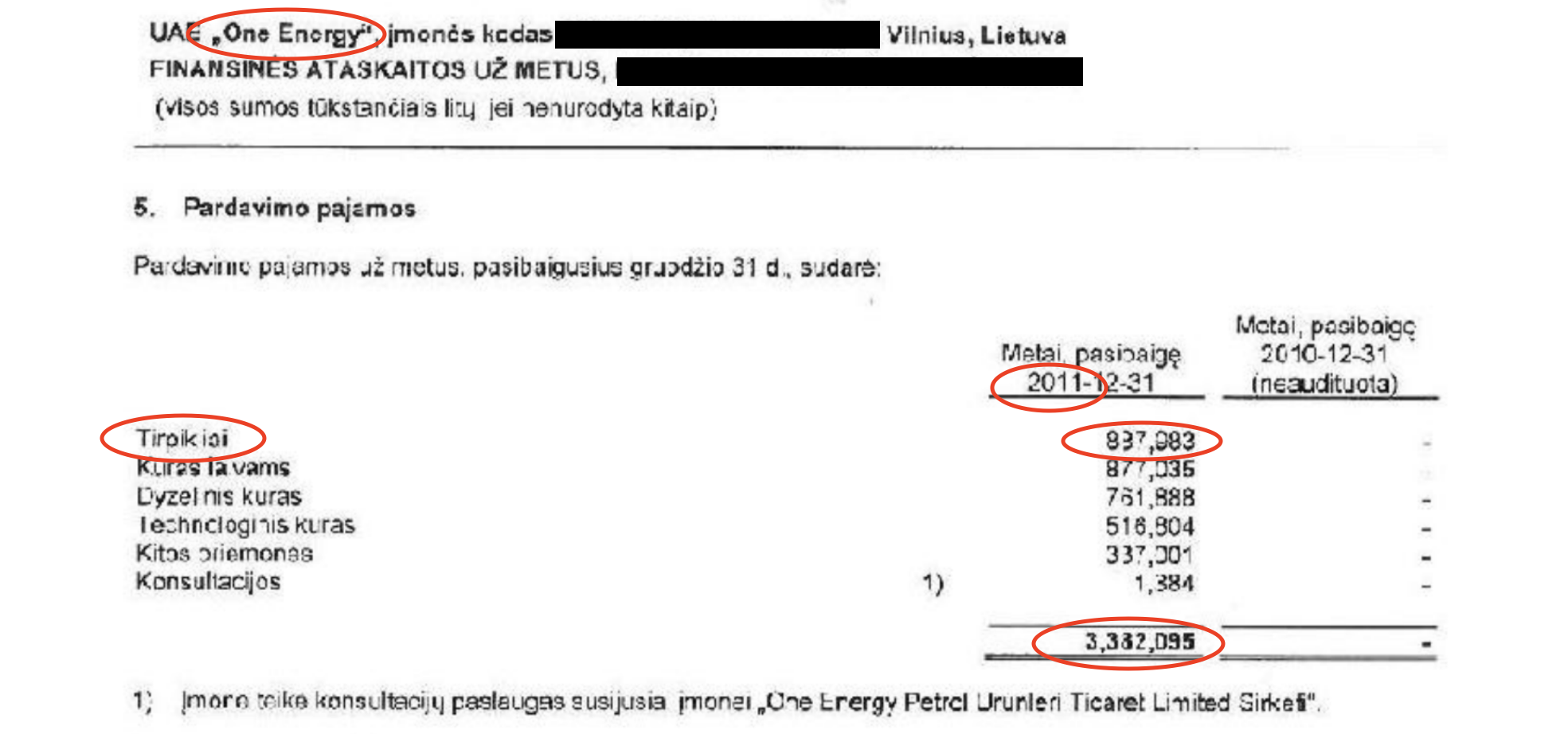

As we found out, their European partners included the Lithuanian company One Energy. In 2011, its revenues exceeded $1 billion, and a quarter of its revenues came from solvents and diluents.

According to our source, the largest volumes of supplies went through the Savoil company owned by Vitold Tomaševskij. In five months of operation in 2011, the revenue of the company exceeded $800 million, and in 2012 it approached $5 billion. The net profit for two years was more than $80 million.

Tomaševskij is a long-time associate of disgraced Belarusian businessman Yury Chyzh. We discussed their longstanding contacts in an earlier investigation. Their main joint project is a scheme involving solvents and diluents. Together with the Lithuanian Siena investigative centre, we found that on the Belarusian side, Yury Chyzh's company Triple and two other companies – Triple-Energo and Belneftegaz – were involved in this crook business. Both companies are linked to the businessman Aliaksei Aleksin: Triple-Energo was run by him, and Belneftegaz was owned by him and his wife.

At that time, Aleksin worked for Chyzh and is believed to have thought up the solvent and diluent scheme.

In January 2012, at the height of this scheme, Aleksin opened the account in the Swiss bank, which later held up to $36 million. We called Aleksin to find out where he got the money from, but he declined to comment. In 2012, Russia shut down the scheme, and two years later Aleksin closed his Credit Suisse account.

The paths of Chyzh and Aleksin diverged. Chyzh has been behind bars twice, while Aleksin has become one of the most influential businessmen in Belarus. In 2021, he was sanctioned by the EU and US as President Aleksandr Lukashenko's «money bag».