Our investigation revealed that 1,031 Belarusian citizens have signed contracts with the Russian military since Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The number of Belarusian contractors increased dramatically from just 6 people in 2022 to 235 in 2023 and 517 in 2024.

Key findings:

- Most contractors (498) hold the lowest military rank

- Among the contractors we identified: 52 were industrial workers; 31 had criminal records; 9 were former security forces members

Particularly concerning discoveries:

- Many Belarusians cannot leave service even after their contracts expire

- Russia offers simplified citizenship to attract contractors

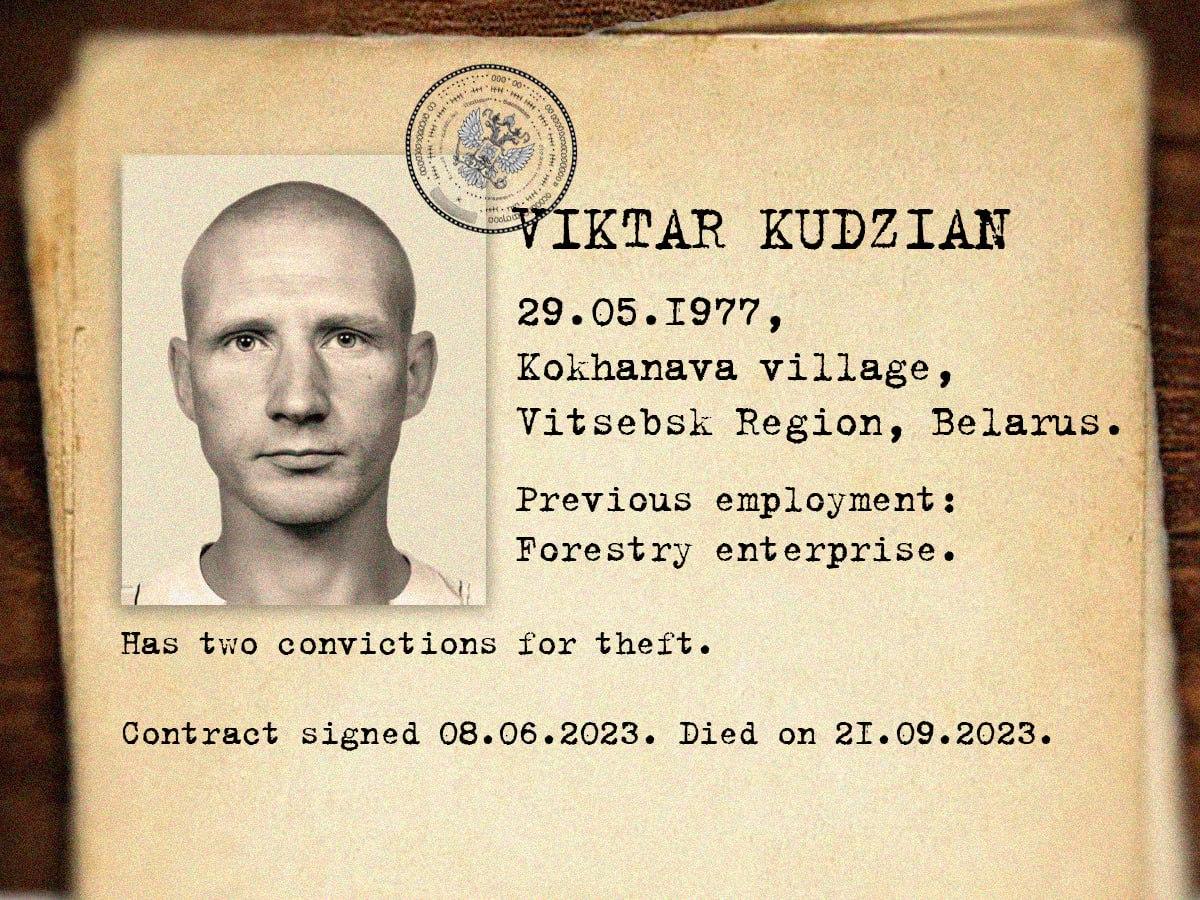

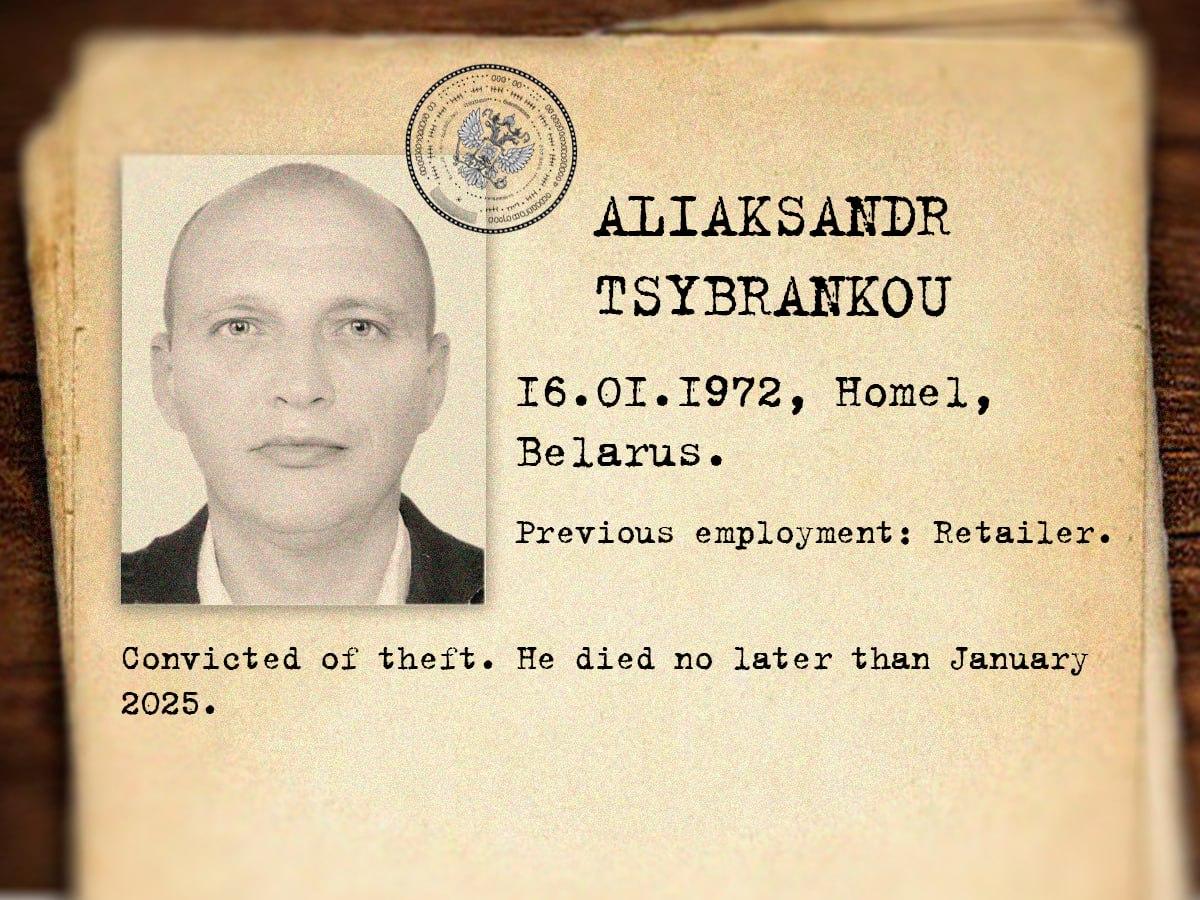

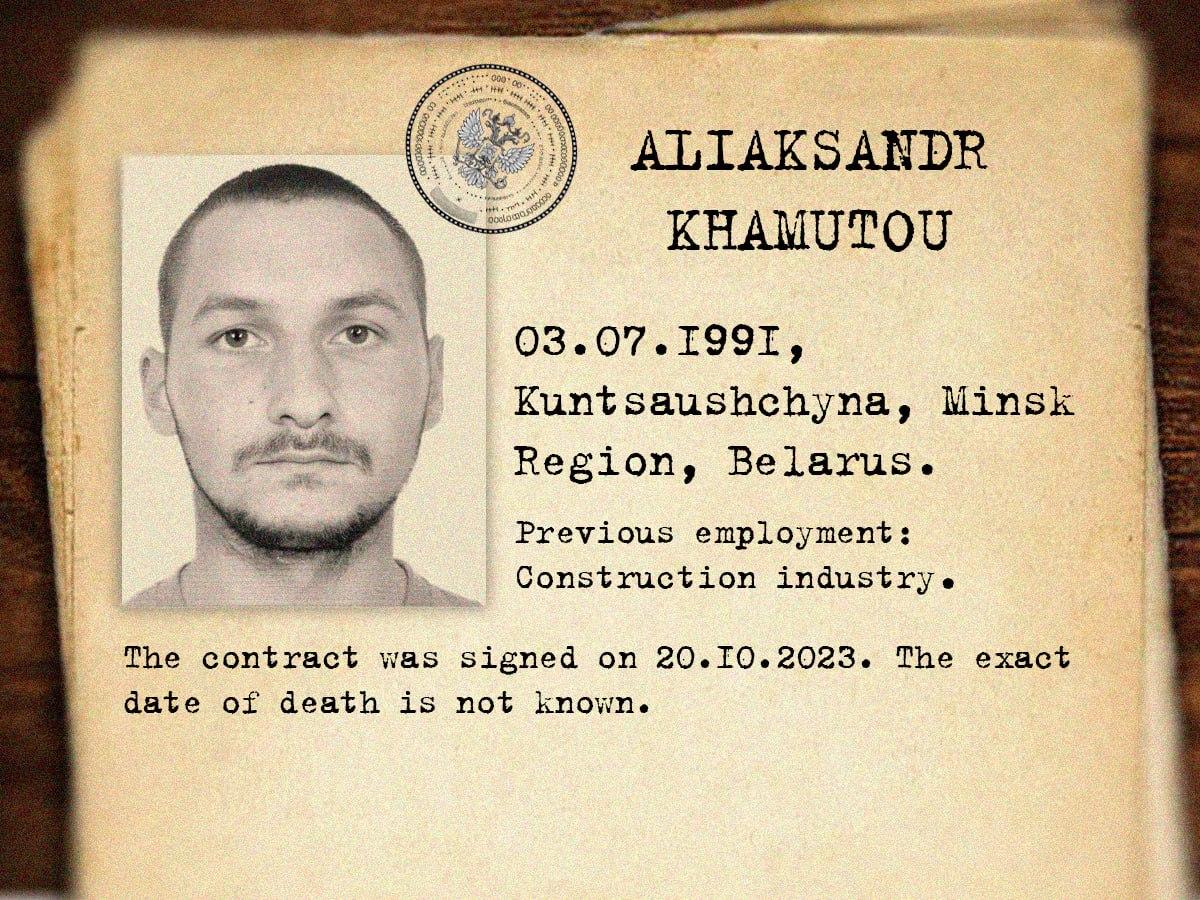

- According to Ukrainian intelligence, 105 Belarusian contractors have died and 84 are missing in action

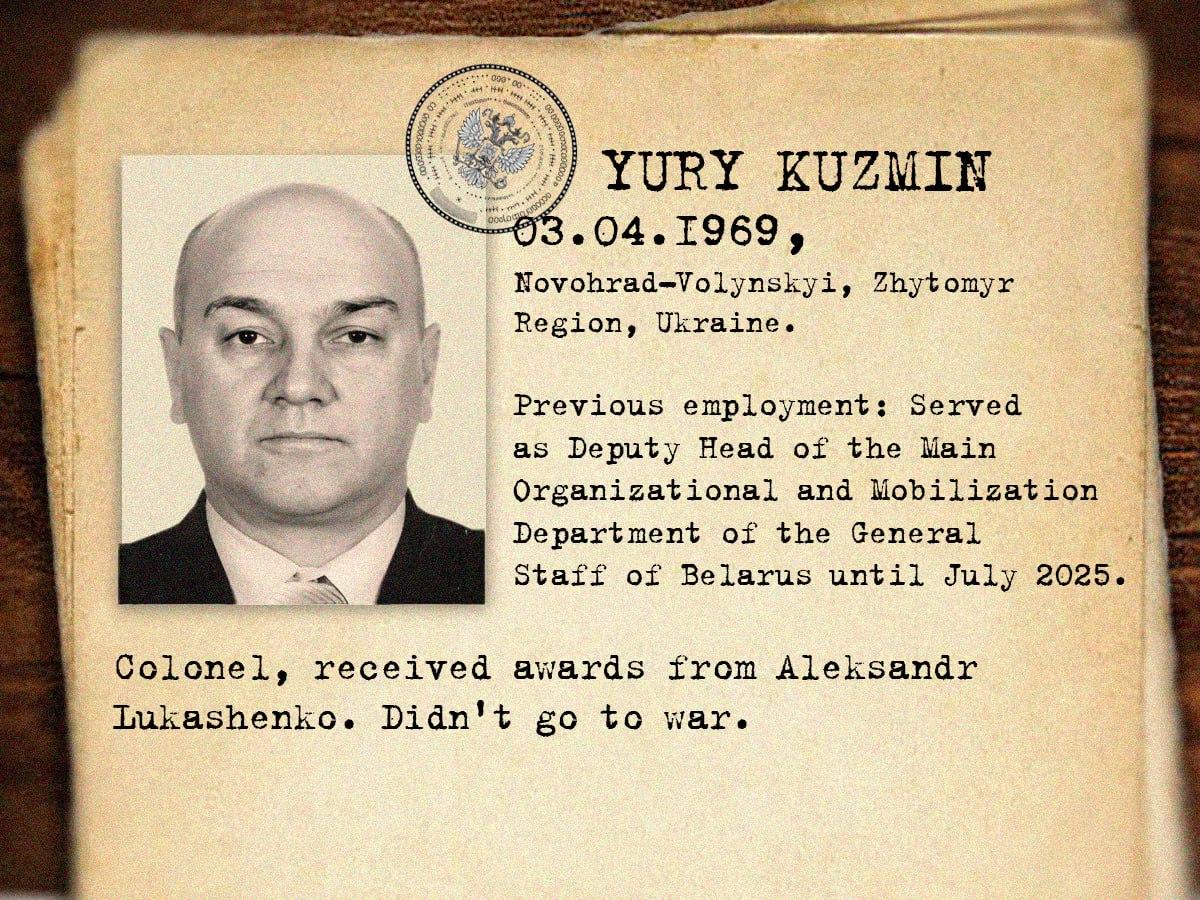

A significant revelation came from deputy head of the Main Organizational and Mobilization Directorate of the General Staff of Belarus Staff Yury Kuzmin, who confirmed that Belarus plans to create a similar recruitment system to Russia's, including recruiting foreigners through special centers.

The findings highlight how Russian trenches have indeed become a trap for many Belarusians, with almost one in five either dead or missing in action, while others find themselves unable to leave service despite expired contracts.

The Belarusian Investigative Center has learned how many Belarusian citizens signed contracts to fight for Russia in the war against Ukraine. The BIC talked with some of these people to hear their stories and to understand their motives.

This article was prepared in cooperation with the Ukrainian investigative project Slidstvo.Info, with the support of the Belarusian hacktivist group Cyber Partisans, the Ukrainian cyber community KibOrg and the Belarusian initiative BelPol.

1,031 Belarusian citizens signed contracts with the Russian military since the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, according to the data the BIC obtained from Ukrainian military intelligence. The first contract was signed in July 2022, the most recent one was signed this year on July 15.

The BIC also received the list of 71 Belarusian citizens who visited the Unified Military Service Recruitment Center in Moscow from April 2023 to early June 2024. The list was provided by the Russian colleagues from the investigative website “Important Stories” (the information was leaked from the Unified Medical Information and Analytical System of the Russian Federation).

The BIC has communicated with 19 Belarusians from the list – some of them joined the Russian war against Ukraine, but some others changed their minds. The BIC journalist pretended to be an employee of the Unified Military Service Recruitment Center in order to obtain their stories and understand their motivations.

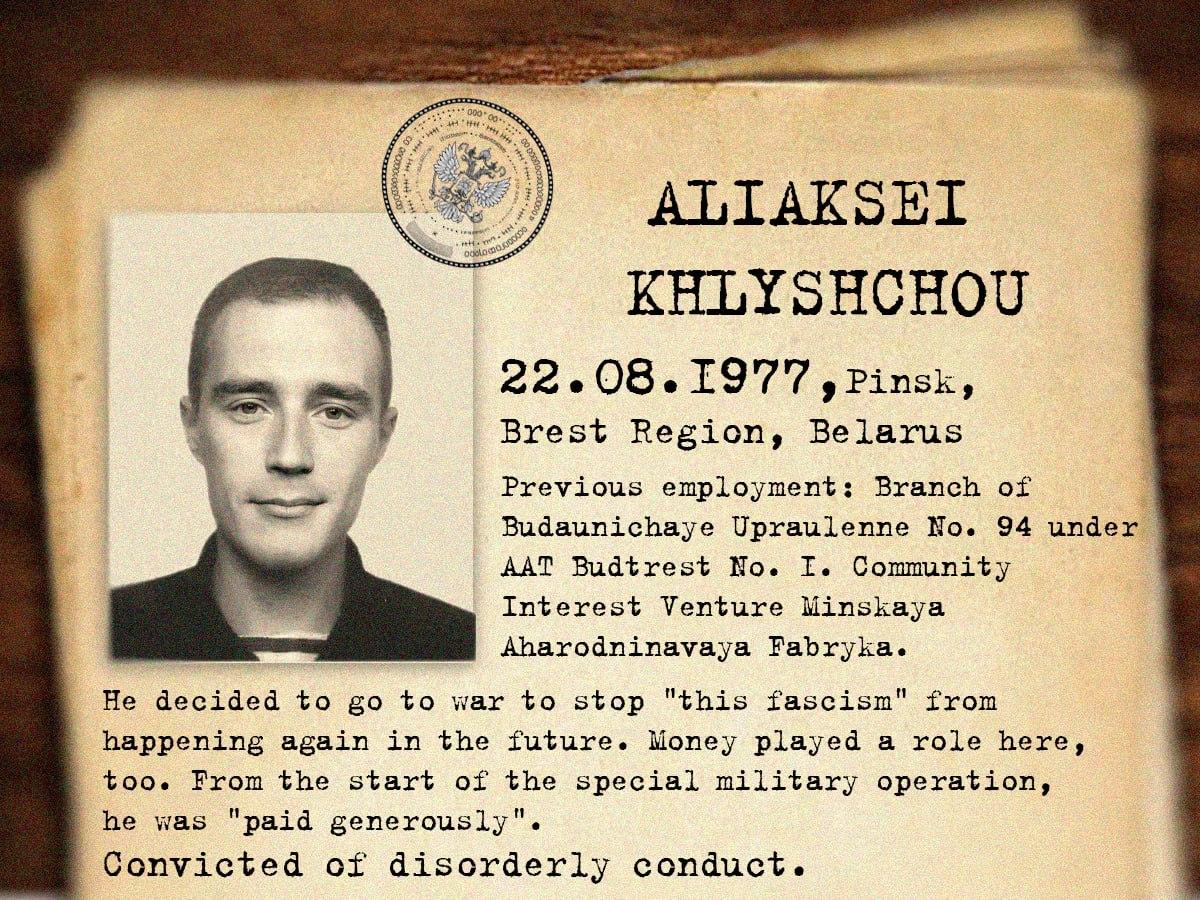

"Get back to his roots"

"Four of our friends (unfortunately, one is no longer with us), and so we decided to go together and help, and make some contribution to ensure that this disgrace, this fascism, Nazism and abuse of civilians does not happen in the future". This is how 48-year-old Aliaksei Khlyshchou explained his motivation to join the Russian war against Ukraine. He talked to the BIC journalist for almost 20 minutes. The man explained that he decided to "get back to his roots" (his father is a Russian officer). He told the journalist how the payments for participation in the so-called “Special Military Operation” were cut, and complained that there are no rehabilitation programs for those who returned from the war.

Aliaksei Khlyshchou has two children. In the past he worked in Belarusian construction companies, at a factory, and he has a criminal conviction for hooliganism. In 2017, he moved to Russia, and after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, he signed a contract with the Russian army.

The background of Belarusians in the Russian military

52 out of the 71 people on the list had worker specialties before they decided to join the Russian military. For example, 11 of them worked in construction, 6 were drivers, 7 were collective farm workers. [*]

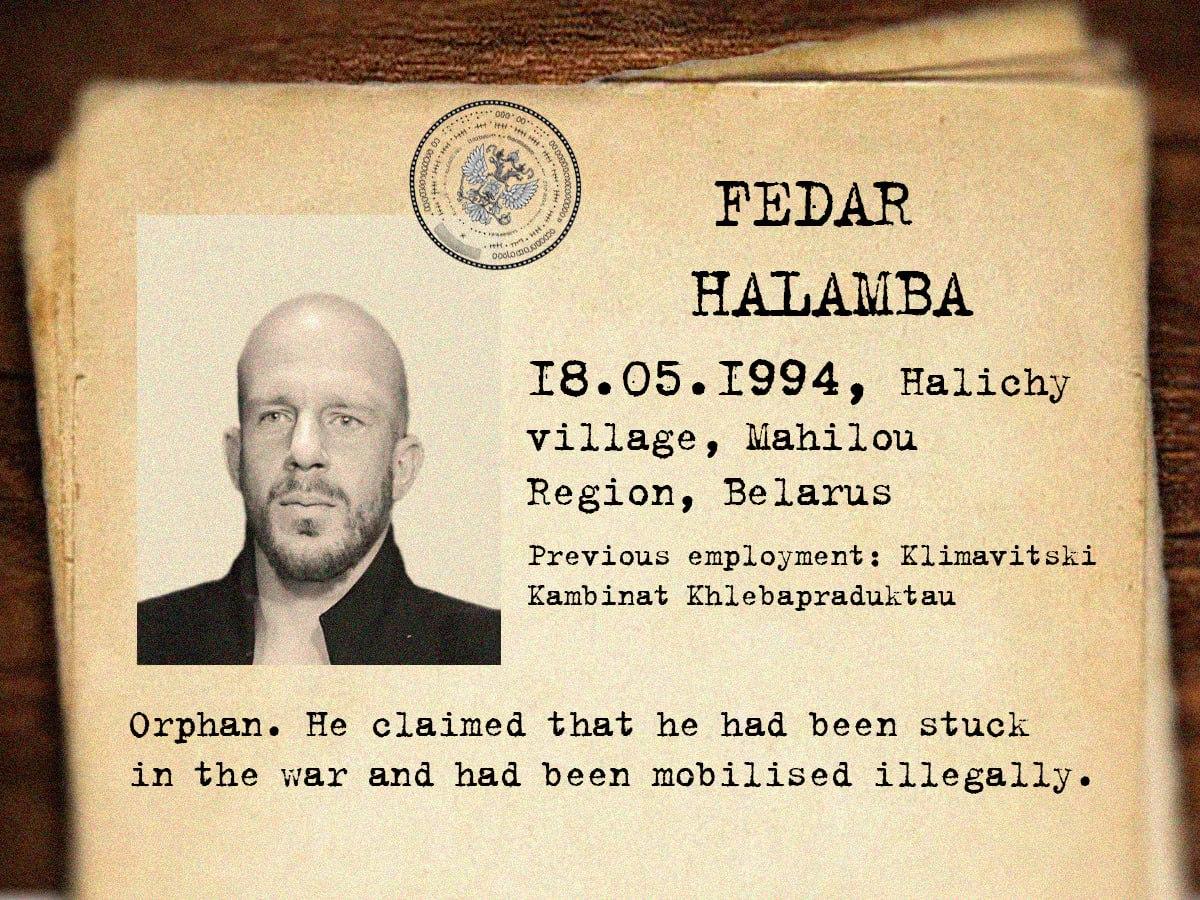

31-year-old Fedar Halamba worked at a bread-baking complex in the town of Klimavichy in eastern Belarus. In 2016 his photos with arms and the flag of the so-called “Donetsk People's Republic” appeared on his page in the social network Odnoklassniki. Halamba says that he signed a contract with the Russian military, but later he was mobilized even before he obtained the Russian passport. [*]

While working on the investigation, BIC journalists examined

several lists of Belarusian contract soldiers. These included a leak from the Moscow medical database (EMIAS), a list of mercenaries obtained from Ukrainian intelligence and lists from open sources, such as the one compiled by the Ukrainian I Want to Live project. To verify the data, we also used the following sources:

- open data (information about the dead and wounded, their social media, news, the Myrotvorets website);

- BelPol data (criminal records, debt information, wanted persons);

- Cyber Partisans data (document extracts, employment records);

- phone calls to individuals on the list — we called everyone and recorded 19 conversations.

"I have problems with my previous military unit, because my previous military unit was disbanded, that's it. And my contract was already ending by that time, and instead of dismissing me, they mobilized me. They mobilized me in Donetsk. An investigation is already underway, but, as the lawyer says, at that time I was not a citizen of the Russian Federation," Halamba said.

Fedar Halamba has not yet decided whether he is ready to sign a new contract if he manages to challenge his mobilization, which he considers illegal. Contract soldiers, unlike those mobilized without a contract, receive additional one-time payments.

Criminal records

Out of the 71 Belarusians on the list 31 people have criminal convictions. 21 out of these 31 people have signed contracts with the Russian military, three of them have not signed yet, but two of those three are still planning to do it. The BIC journalists were unable to contact the other seven of the 31.

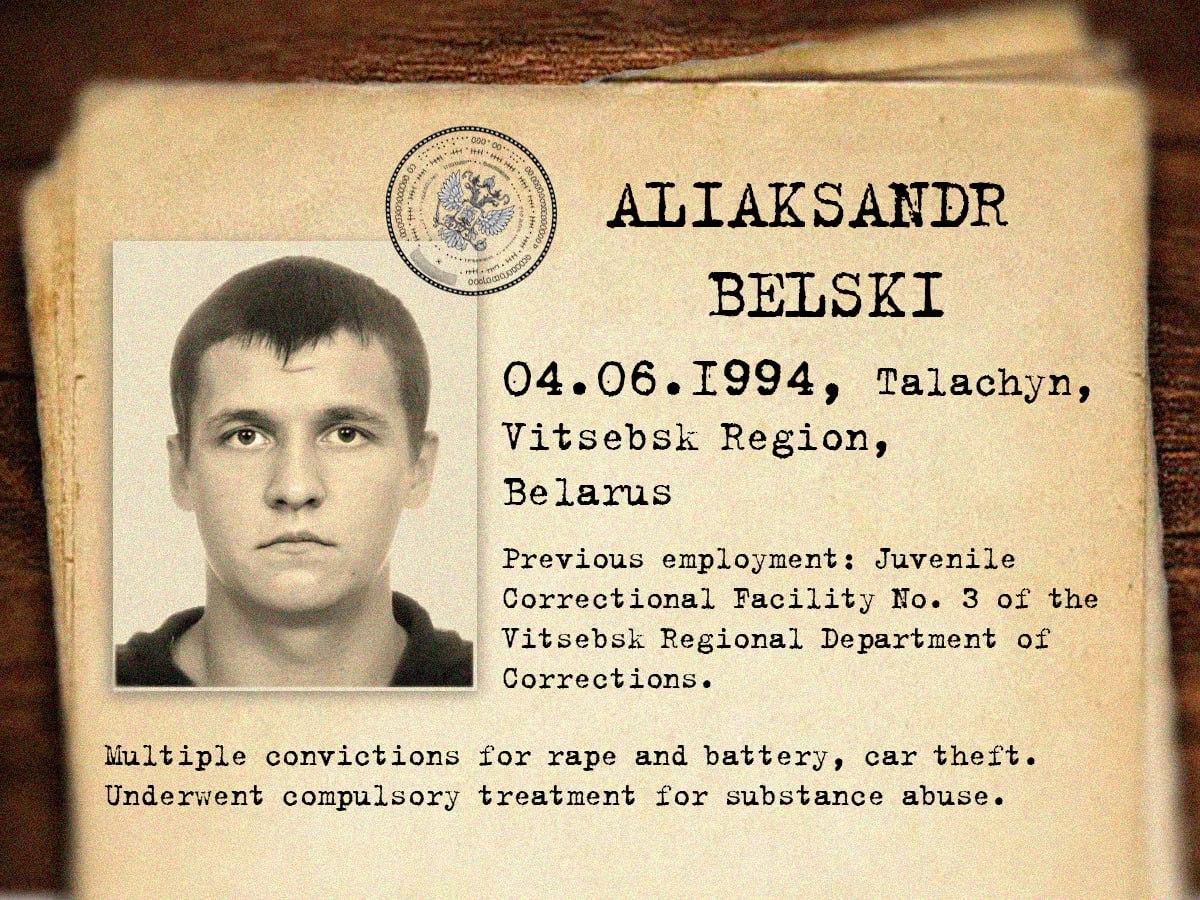

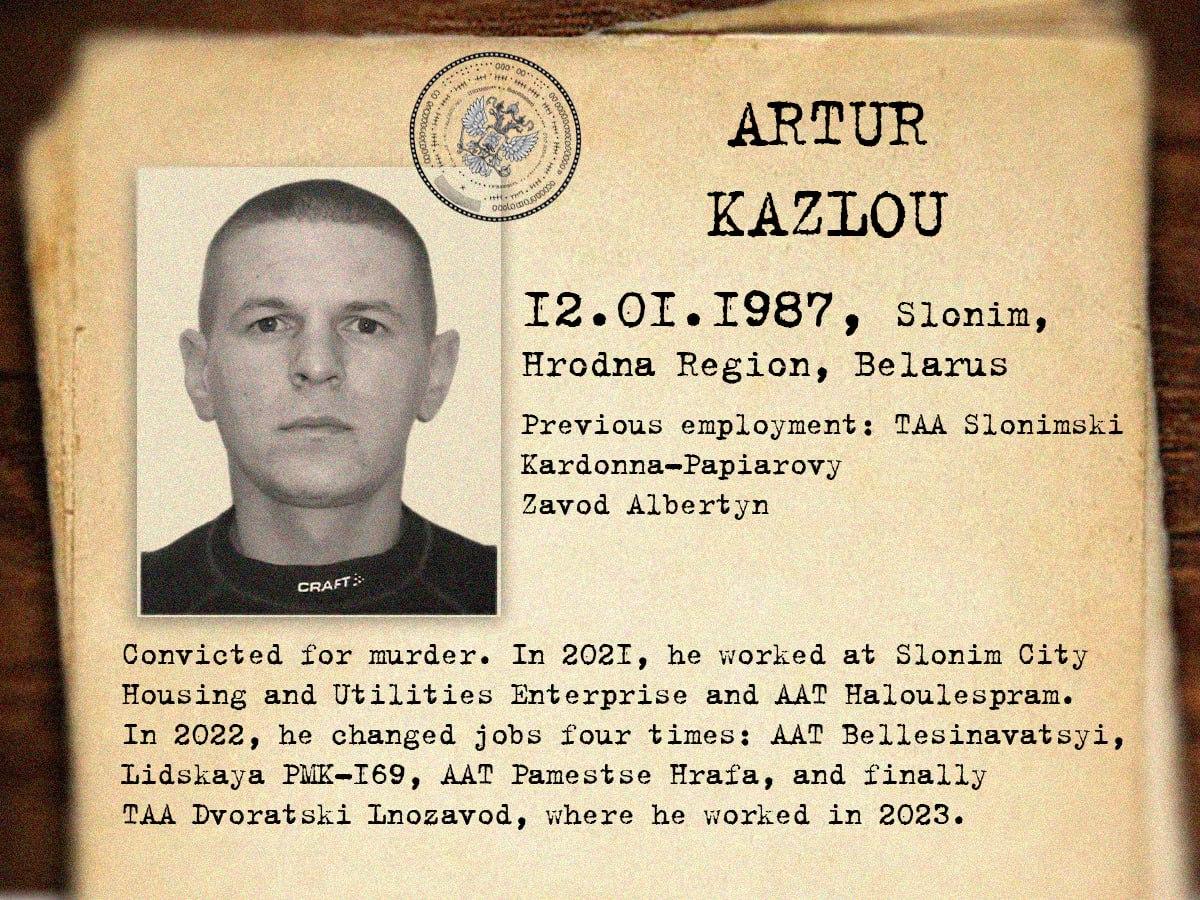

Artur Kazlou, a person on the list, served time for murder. Aliaksandr Belski received 8 years in a maximum security penal colony for beating a woman with a stool and then raping her. The BIC has not managed to communicate with Kazlou and Belski, so it is not clear whether they signed contracts with the Russian military. [*]

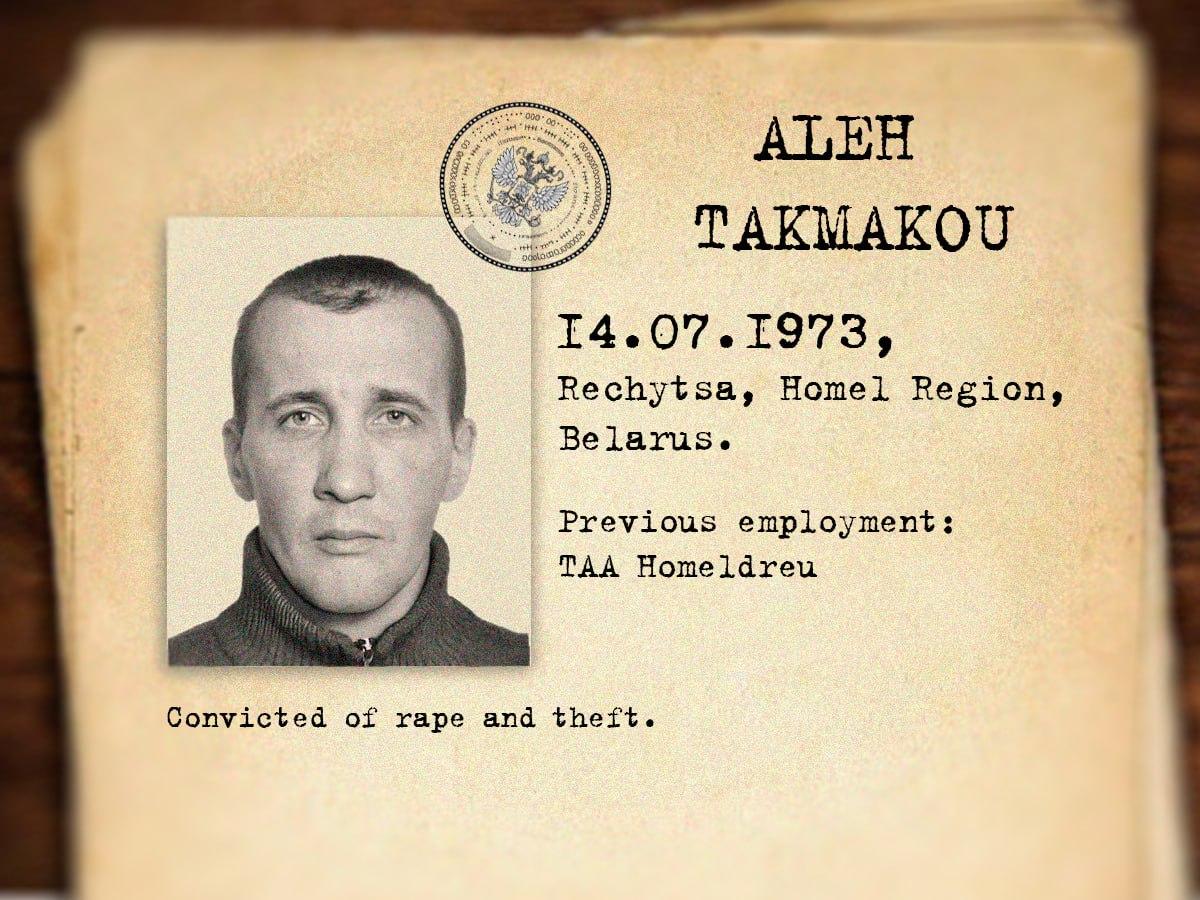

But Aleh Takmakou, a 52-year-old native of the Homel region in southern Belarus, convicted of rape and repeated theft, successfully passed the selection for a contract with the Russian Armed Forces, despite the Russian federal law that excludes such a possibility.

The BIC journalist called Takmakou on June 30. The man said that he was at the "Special Military Operation":

"My contract has ended, no one is letting me go. I just serve without a contract."

According to Takmakou, he cannot return home because he has Russian citizenship in addition to the Belarusian one. According to a decree by the Russian President Vladimir Putin, a contract with a Russian citizen is valid until the end of the “partial mobilization period” that is in force in Russia now.

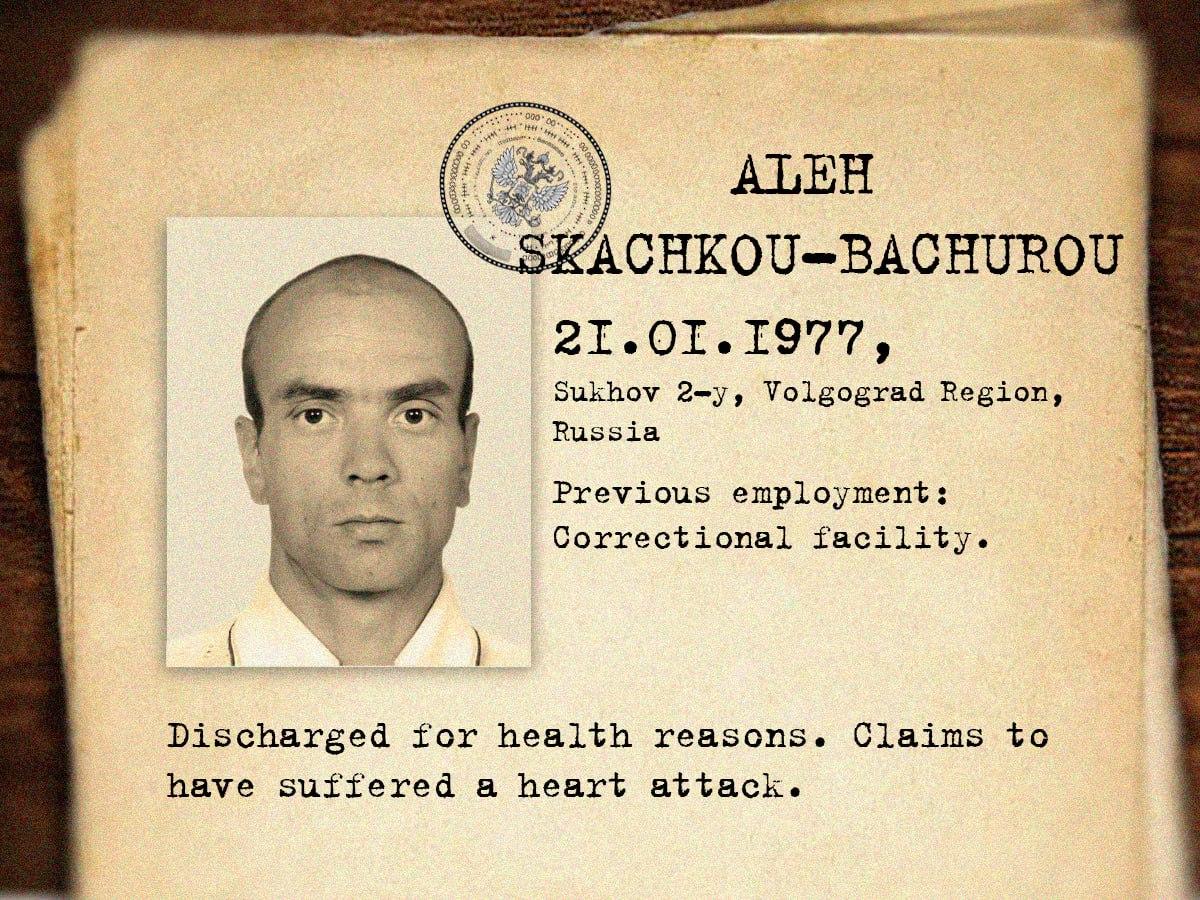

Aleh Skachkou-Bachurou also has a criminal record. He is a former employee of a correctional colony and he signed a contract with the Russian military, but he did not go to the war. Not because of his criminal record, but because of his health. [*]

"On March 28, I was discharged due to health reasons. I had a heart attack. <...> In Belarus, I worked as an operative in places of detention," Skachkou-Bachurou said. When a journalist asked if he was still interested in collaborating with the Russian Defense Ministry, the man answered in the affirmative.

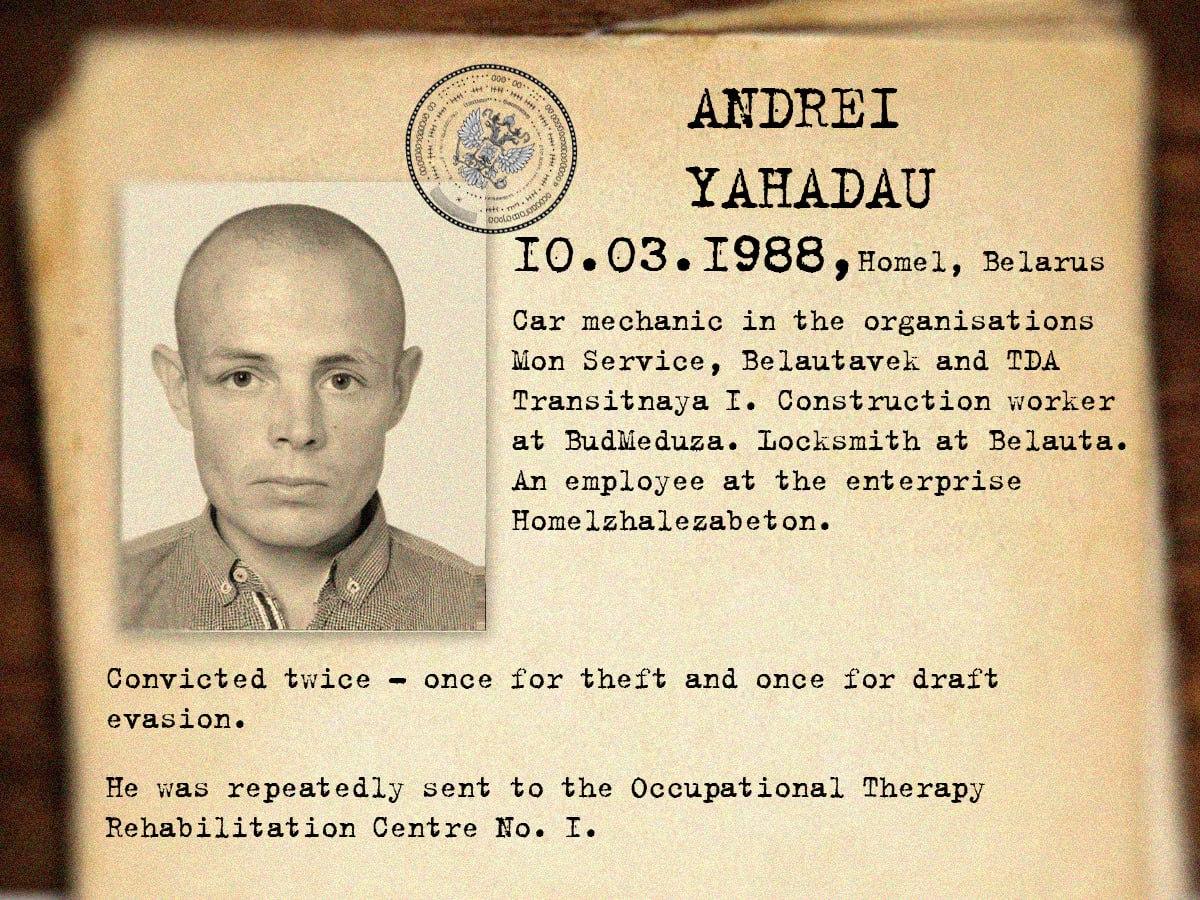

Andrei Yahadau, convicted of theft and draft evasion, did not dare to sign a contract after visiting the recruiting center in Moscow. "You understand that there may be some kind of... criminal prosecution" he says. [*]

In practice, the risk of prosecution of Belarusians for participating in the war on the side of Russia is minimal, says Mikhail Kirilyuk, a lawyer for the National Anti-Crisis Management, Belarusian opposition's cabinet in exile.

"There is an article called "Mercenarism" [in Belarus' criminal code], but there are many exceptions to prosecution under this article,” he says.

Kirilyuk explains that in order to be prosecuted under this article, a person must serve for money in private formations of a foreign state without the consent of the authorities of that state and also without citizenship or permanent residence of that country (in this case, the Russian Federation). When all these conditions are met, a mercenary can be held accountable, Kirilyuk added.

“You are Russian, let's go until victory”

Among the 71 people on the list the BIC journalists found nine former employees of the Belarusian security agencies. Six of them definitely signed contracts with the Russian military.

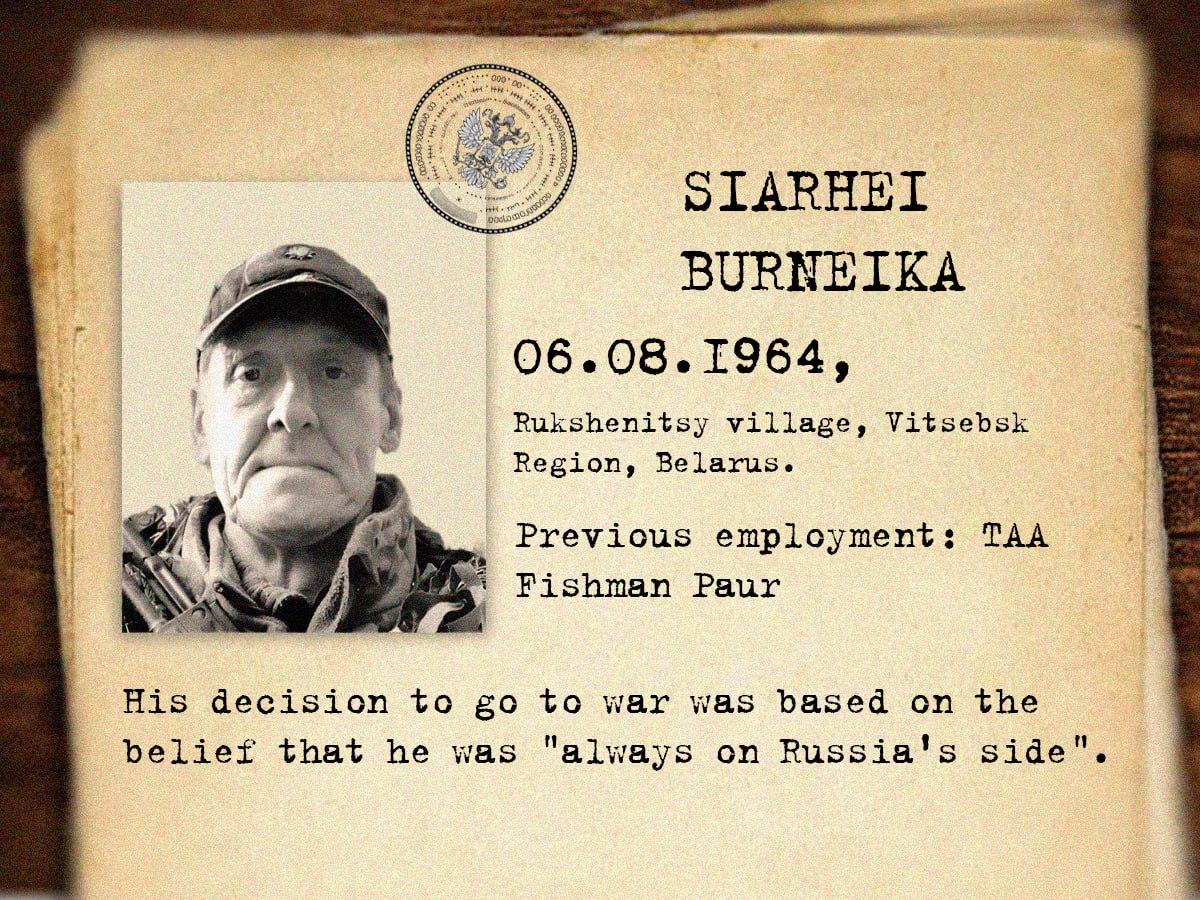

One of these people is 61-year-old Siarhei Burneika. [*]

In 1999, he commanded a department of the paramilitary fire service of the Vitebsk District Department of Internal Affairs. "I am always for Russia. That's the first thing. I was on the front lines. I finished [the contract] a year and a half ago," Burneika says.

Believing that he was talking to a representative of the Unified Recruitment Center, Burneika sent the BIC journalist a copy of his contract. It becomes clear from it why some Belarusians want to receive Russian citizenship before signing the contract: unlike a foreigner, a Russian mercenary receives a military mortgage, free medical care and insurance. But it is extremely difficult to quit. Burneika succeeded because of his age.

Maksim Serykau, a former road patrol inspector in Belarus, also received a Russian passport. Now he complains that he cannot quit after the end of his contract. He also speaks about discrimination: he serves in a sergeant position, although in Belarus he received the rank of captain.

“The thing is that when it is convenient, I am a Belarusian, the rank is not awarded, and so on. And to dismiss you, let's say, at the end of the contact - well, you are Russian, let's go until victory... I am currently in a sergeant position, I receive a sergeant's salary,” says Serykau. [*]

"They intentionally give them simplified citizenship,” explains Volodymyr Yavorskyy, Ukrainian human rights activist of the Center for Civil Liberties. “That is a mechanism for luring people and, of course, they deceive them a little in this sense, this is obvious. Because they need to look for a resource not from their own citizens”.

Belarusian General Staff learning from the Russian model

In 2023, there was an unusual visitor on the list of Belarusians at the Unified Military Service Recruitment Center in Moscow – Yury Kuzmin, deputy head of the Main Organizational and Mobilization Directorate of the General Staff of Belarus. [*]

Colonel Kuzmin has overseen conscription in Belarus for about the last ten years. The BIC journalist called Kuzmin and introduced herself as an employee of the Moscow Recruitment Center.

“We were there on a tour, familiarization. We were shown around, we, Belarusians, were adopting your experience on these issues: on the procedure for concluding contracts, attracting foreign citizens," Kuzmin said.

He added that Belarus plans to create a system of recruitment similar to the Russian one, which will allow recruiting foreigners through special centers.

Based on information from open sources, BIC journalists calculated that at the end of 2024, at least 44,000 soldiers served under contract in Belarus (about 4,000 of them were women). In 2021, there were about 27,000 soldiers under contract.

The main increase in numbers – by half – occurred in 2023. Aleksandr Lukashenko ordered the construction of a contract army based on the experience of the Russian private military company Wagner.

“I want to keep these guys [Wagner fighters] in the Armed Forces of our country. And, based on them, more actively create a contract army,” Lukashenko said then.

Almost one in five dead or MIA

Among the prisoners of war captured by the Ukrainian military Belarusians are fourth in numbers among the non-Russian citizens – behind Uzbeks, Tajiks and Nepalese. The Ukrainian investigative project Slidstvo.Info received this information from Ukraine's Coordinating Headquarter for Treating Prisoners of War.

Ukrainian military intelligence told BIC that there have been 105 confirmed deaths of Belarusian contract soldiers fighting for Russia (this is more than 10% of their total number). Another 84 (about 8%) are missing in action. That means almost one in five of them is either dead or MIA.